Wenamon es una historia escrita por un escritor anónimo en el reino de Ramses XI (1099-1069 a.C.)

La historia trata de un hombre que debe de hacer una barca para transportar una imagen del dios Amón. Wenamon debe de ir hacia Biblos por la madera, pero cuando llega allí tiene muchos contratiempos. Se le exige un pago, algo que normalmente no sucedía gracias al poderío del imperio egipcio.

Tras conseguir su nave, se embarca para regresar a Egipto pero un viento le lleva a Chipre donde es atacado. Entonces se acabó el papiro.

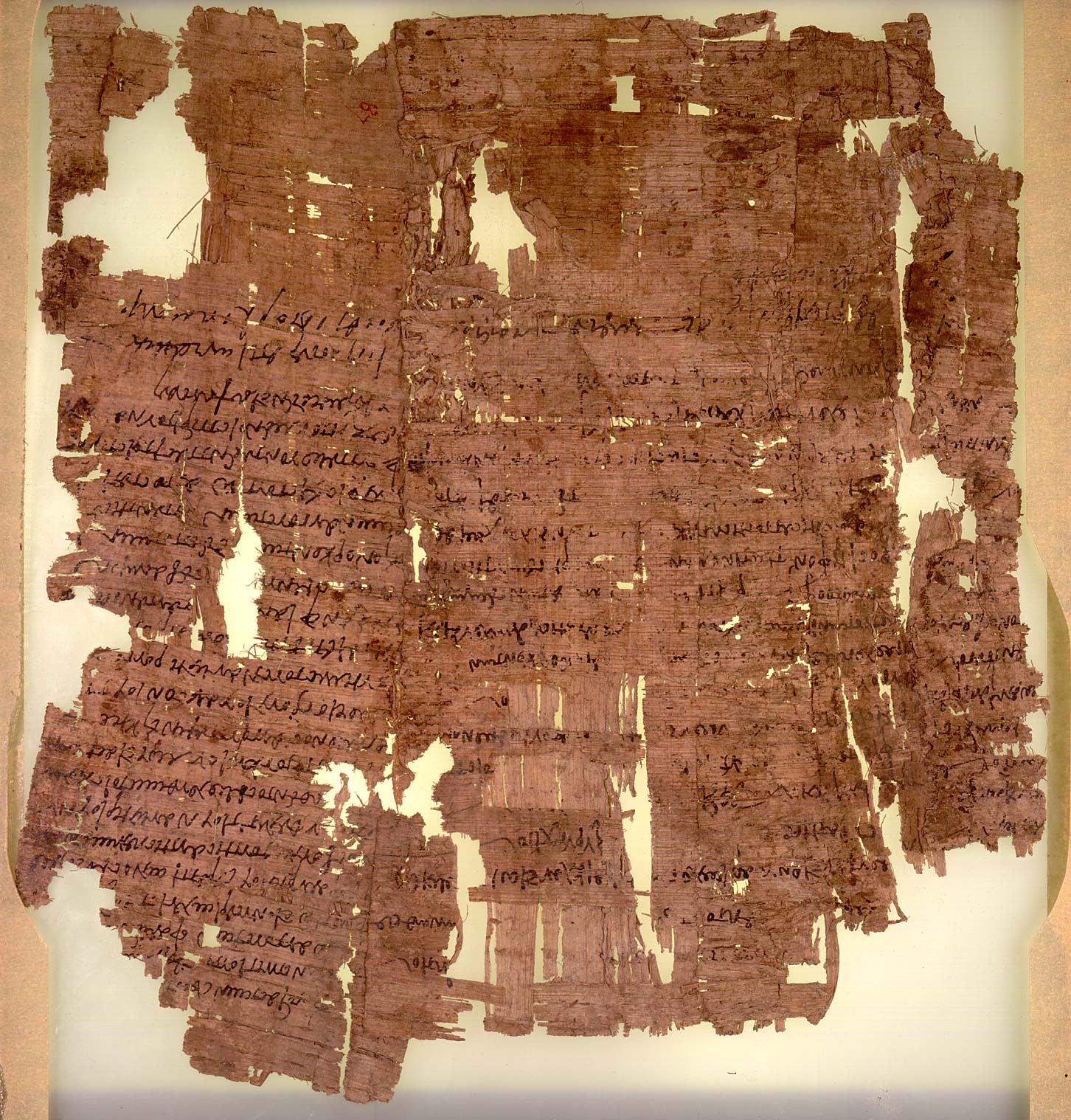

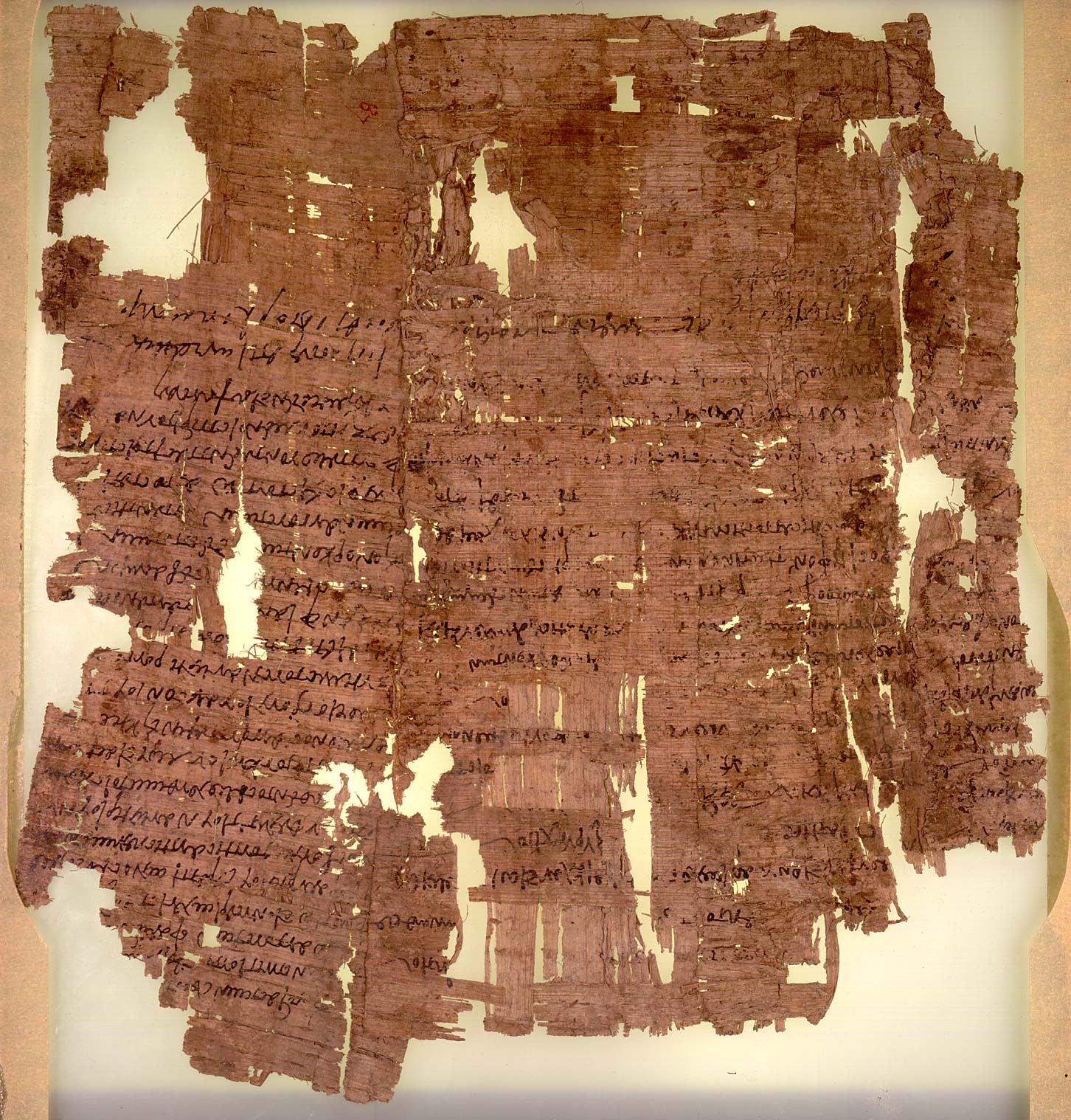

Papiro Puskhin 120

El relato del viaje de Unamón

Características:

Se conservan 142 líneas distribuidas en dos páginas, la primera de 59 líneas y la segunda de 83, en piezas casi iguales de unos 18 cm de altura cada una. La escritura es clara, con tinta negra y ocasionalmente roja al principio. El texto está escrito a lo ancho del papiro, cruzando las fibras verticales, en lugar de a lo largo como era común en otros papiros. Este mismo método fue también empleado en algunos cuentos del mismo período e incluso posteriores, como el papiro Anastasi VIII.

Barco egipcio

Estado: Bueno pero falta el final del texto, correspondiente a la tercera página. Contiene algunas lagunas, principalmente en la primera página; la segunda está prácticamente completa.

Escritura: Hierática.

Tipo: Literario.

Localización: Museo Pushkin de Bellas Artes. Moscú.

Contenido: La única copia del relato del Viaje de Unamón que ha llegado al día de hoy.

En él se describe el viaje realizado a Biblos en busca de madera para su señor, el faraón.

El texto refleja la decadencia de Egipto a comienzos de finales del Reino Nuevo. La situación no es la misma ya que en épocas anteriores, cuando cualquier enviado del faraón a Canaán era tratado con los mayores honores y sus peticiones eran atendidas con la máxima rapidez y eficacia.

Época: XXI dinastía aunque podría ser una copia de un documento anterior.(1) G. Möller lo sitúa en la XXII dinastía. La acción se desarrolla en la XX dinastía.

Procedencia: Encontrado en el Hiba y adquirido por Golenischeff en 1891.

Imágenes: Comienzo del papiro

Comienzo del papiro de Moscú(Puskhin 120)

Cuento de Unamón. Museo Pushkin (Moscú)

Fuente: Galán, José Manuel. Cuatro viajes a la Literatura del Antiguo Egipto.

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid, 1998

http://www.egiptologia.org/fuentes/papiros/moscu120/#1

Textos:

-

Gardiner, Alan H. Late Egyptian Stories. Biblitheca Aegyptiaca I. Brussels 1932.

-

Galán, José Manuel. Cuatro viajes a la literatura del Antiguo Egipto. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid, 1998.

-

Goedicke, H. The Report of Wenamun, Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, 1975.

-

Lalouette, Claire. Textes sacrés et textes profanes de l’anciene Égypte, II, Mythes, contes et poésie. Gallimard, Paris 1987.

-

Lefevbre, G. Romans et contes de l’époque pharaonique. Maisonneuve, Paris, 1949. Existe una traducción al castellano de José Miguel Serrano Delgado, con el título: Mitos y cuentos egipcios de la época faraónica. Editorial Akal, 2003

-

Lichtheim, Miriam. Ancient Egyptian Literature. A Book of Readings. Volume II: The New Kingdom, Berkeley-Los Angeles-London, University of California Press, 1976.

-

Maspero, G. Les Contes populaires de l’Égypte ancienne. Paris, 1911. Existe una traducción al castellano de Mario Montalban con el título Cuentos del Antiguo Egipto. Ediciones Abraxás . Barcelona, 2000.

-

Wente, Edward. F. The Report of Wenamun en The Literature of Ancient Egypt. An Anthology of Stories, Instructions and Poetry. William Kelly Simpson (Editor). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973.

Otros estudios:

-

Bordreuil, P. A propos du Papyrus de Wen Amon. Semitica XVII. Cahiers publiés par l’Institut d’Études Sémitiques de l’Université de Paris, avec le concours du. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (n° XVII). Paris, 1967.

-

Bunnens, G. La mission d’ Ounamon en Phénicie. Point de vue d’ un non-Égyptologue. Rivista di Studi Fenici 6 (1978).

-

Caminos, Ricardo A. A tale of woe : from a hieratic papyrus in the A. S. PUSHKIN Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. Oxford 1977.

-

Egberts, A. The Chronology of the Report of Wenamun revised. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 125.

-

Scheepers, A. Anthroponymes et Toponymes du récit d’ Ounamon, en E. Lipinski (ed.), Phoenicia and the Bible. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 44, Lovaina 1991.

-

Scheepers, A. Le voyage d’ Ounamon: un texte «littéraire» ou «non-littéraire»?,” en C. Obsomer - A.-L. Oosthoek, Amosiadès. Melanges offerts au Professeur Claude Vandersleyen par ses anciens étudiants, Lovaina-la-Nueva, 1992.

Además recomendamos:

(1) Galán, Jose Manuel. Cuatro viajes a la literatura del Antiguo Egipto. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. Madrid, 1998, p 18

- Baines, John R. 1999. “On Wenamun as a Literary Text”. In Literatur und Politik im pharaonischen und ptolemäischen Ägypten: Vorträge der Tagung zum Gedenken an Georges Posener 5.–10. September 1996 in Leipzig, edited by Jan Assmann, and Elke Blumenthal. Bibliothèque d’Étude 127. Cairo: Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire. 209–233.

- Caminos, Ricardo Augusto. 1977. A Tale of Woe from a Hieratic Papyrus in the A. S. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Oxford: The Griffith Institute.

- Egberts, Arno. 1991. “The Chronology of The Report of Wenamun.” Journal of Egyptian Archæology 77:57–67.

- ———. 1998. “Hard Times: The Chronology of ‘The Report of Wenamun’ Revised”, Zeitschrift fur Ägyptischen Sprache 125 (1998), pp.93-108.

- ———. 2001. “Wenamun”. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 3 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 495–496.

- Eyre, C.J. [1999] “Irony in the Story of Wenamun”, in Assmann, J. & Blumenthal, E. (eds), Literatur und Politik im pharaonischen und ptolemäischen Ägypten, IFAO: le Caire, 1999, pp.235-252.

- Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 1932. Late-Egyptian Stories. Bibliotheca aegyptiaca 1. Brussel: Fondation égyptologique reine Élisabeth. Contains the hieroglyphic text of the Story of Wenamun.

- Goedicke, Hans. 1975. The Report of Wenamun. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Helck, Hans Wolfgang. 1986. “Wenamun”. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie, edited by Hans Wolfgang Helck and Wolfhart Westendorf. Vol. 6 of 7 vols. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. 1215–1217

- Коростовцев, Михаил Александрович [Korostovcev, Mixail Aleksandrovič]. 1960. Путешествие Ун-Амуна в Библ Египетский иератический папирус №120 Государственного музея изобразительных искусств им. А. С. Пушкина в Москве. [Putešestvie Un-Amuna v Bibl: Egipetskij ieratičeskij papirus No. 120 Gosudarstvennogo muzeja izobrazitel'nyx iskusstv im. A. S. Puškina v Mockva.] Памятники литературы народов востока (Волъшая серия) 4. [Moscow]: Академия Иаук СССР, Институт Востоковедения [Akademija Nauk SSSR, Institut Vostokovedenija].

- Leprohon, R.J. 2004. “What Wenamun Could Have Bought: the Value of his Stolen Goods”, Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World: Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford (ed. G.N. Knoppers and A. Hirsch; Probleme der Ägyptologie; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2004)

- Sass, Benjamin. 2002. “Wenamun and His Levant—1075 BC or 925 BC?” Ägypten und Levante 12:247–255.

- Scheepers, A. 1992. “Le voyage d’Ounamon: un texte ‘littéraire’ ou ‘non-littéraire’?” In Amosiadès: Mélanges offerts au professeur Claude Vandersleyen par ses anciens étudiants, edited by Claude Obsomer and Ann-Laure Oosthoek. Louvain-la-neuve: [n. p.]. 355–365

- Schipper, Bernd Ulrich. 2005. Die Erzählung des Wenamun: Ein Literaturwerk im Spannungsfeld von Politik, Geschichte und Religion. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 209. Freiburg and Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Freiburg and Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-53067-6

- de Spens, Renaud. 1998. « Droit international et commerce au début de la XXIe dynastie. Analyse juridique du rapport d’Ounamon », in Le commerce en Egypte ancienne, éd. par N. Grimal et B. Menu (BdE 121), Le Caire, p. 105-126. See here

EL PERSONAJE Y SU ÉPOCA

| Wenamón 1065 a. C.- |

|

| Cargo |

Sacerdote. |

| Dinastias |

XX-XXI, (Reino Nuevo/Tercer prdo. Intermedio). |

| Ubicacion |

Tebas. |

| Reinados |

Ramsés XI, |

En aquel tiempo, Egipto estaba dividido en dos partes: el Sur, gobernado por Herihor, y el Delta dominado por Smendes. Cuando se quiso construir la embarcación sagrada de Amón, Wenamón fue enviado a Biblos para conseguir la madera. Allí fue engañado y maltratado, y tras conseguir la madera, su barco fue desviado a Chipre donde naufragó. Después de ser llevado ante la reina, desolado, a punto estuvo de ser ejecutado por su incompetencia..

Cananán(Fenicia)

La Biblia y la Arqueología

http://labibliaylaarqueologia.blogspot.com/2007/08/1503-el-perodo-de-los-jueces-wenamn-o.html

Anet, 25-29

Página del Viaje de Wenamon

http://webperso.iut.univ-paris8.fr/~rosmord/hieroglyphes/oun/

The papyrus, now in the Moscow Museum, comes from el_hibeh in Middle Egypt and dates to the early 21st Dynasty shortly after the events it relates.

The papyrus is now in the collection of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, and officially designated as Papyrus Pushkin 120. The hieratic text is published in Korostovcev 1960, and the hieroglyphic text is published in Gardiner 1932 (as well as on-line).

Se han encontrado unos pocos registros procedentes de este período, los cuales tratan de Palestina y pintan el mismo triste cuadro de anarquia, inseguridad y falta de autoridad central y uniforme descrito en la

entrada anterior.

Wenamón (o Wen-Amón), vasallo del rey de Egipto, fue enviado por su señor a la ciudad de Biblos a comprar madera de cedro del Líbano para construir un barco para procesiones religiosas. El viaje de este cortesano egipcio tuvo lugar alrededor del año 1100 a. C., cerca del final del período de los jueces de Israel. Wenamón salió de Egipto para Biblos en un barco extranjero. Su barco se detuvo en Dor, en la costa de Palestina. Aquí le robaron todo el dinero a Wenamón. Se quejó por esto al príncipe de Dor, pero no pudo obtener satisfacción alguna, porque el príncipe rehusó asumir responsabilidad alguna ya que el robo había ocurrido en un barco extranjero. Antes de continuar su viaje Wenamón robó un saco de plata, el cual llevó consigo a Biblos.

Llegó a esa ciudad, pero no pudo obtener una entrevista con el príncipe del lugar, antes bien el capitán del puerto le pedía todos los días que abandonara la ciudad. Wenamón finalmente se dio cuenta que no podría cumplir con su misión, así que decidió buscar un barco y regresar a Egipto. Cuando se embarcaba, un criado del príncipe de Biblos rogó a su señor en forma vehemente que no dejara partir al mensajero de Egipto sin haberlo visto; por lo tanto, se avisó al capitán del puerto que impidiera que Wenamón partiera ese día.

Wenamón no estaba dispuesto a detenerse, pues creía que podía ser asesinado; pero cuando se pidió también al capitán del barco que no zarpara, el viajero se quedó y le fue concedida una audiencia el próximo día en el palacio del rey de Biblos. Allí se le hizo una recepción bastane humillante, pero finalmente tuvo éxito en conseguir una decisión favorable del rey, pues le fueron dadas unas pocas vigas de cedro para que las llevara a Egipto.

Wenamón prometió al rey escribir a su señor para que enviara productos egipcios como pago por la madera solicitada. Lo hizo, y meses más tarde llegó un barco egipcio. Entonces la madera solicitada fue cortada en el Líbano y traída al puerto, en donde se embarco en presencia del rey. De nuevo hubo algunas observaciones humillantes. Wenamón cargó la madera en los barcos, pero para su horror se dio cuenta de que no podía zarpar porque habían llegado barcos de la ciudad de Dor para apresarlo y someterlo a juicio por la plata que se había robado.

Wenamón, completamente abatido, se sentó y lloró. Cuando el rey de Biblos escuchó esto, envió a una de sus jóvenes bailarina egipcias para alegrarlo. También envió a buscar a los capitanes de los barcos de Dor, y les amonestó diciéndoles que él no podía permitir que arrestaran a Wenamón, su huesped, en sus águas territoriales; pero que podían apresarlo mar afuera. Entonces los barcos de Dor navegaron hacia el sur y permanecieron a la espera de Wenamón, pero este se les adelantó navegando hacia el noroeste en dirección a Chipre.

Barco actual en Asuan

Tan pronto como desembarcó en Chipre, fueron atacados por los nativos de esta isla. Con mucha dificultad pudo obtener una audiencia con la reina, a quien Wenamón hizo esta interesante declaración: “¡Señora, he oído en lugares tan lejnos como Tebas, el lugar en donde está (el dios) Amón, que se hace injusticia en todas las ciudades, pero que se hace justicia en la tierra de Alashiya (Chipre). Sin embargo aquí se hace injusticia todos los días!”² La reina entonces tomó medidas de seguridad concernientes a la permanencia del viajero en la noche.

Desafortunadamente, el papiro se interrumpe en este punto y nos deja sin información con respecto a las siguientes aventuras de Wenamón.

Como este documento parece ser el informe original de Wenamón al rey de Egipto, después de su regreso a su tierra, es obvio que sobrevivió y aun consideró su misión como un éxito, pues, de lo contrario, no poseeríamos este manuscrito.

Aunque la historia es bastante interesante en sí misma, es especialmente importante como un documento contemporáneo del período de los jueces. Revela las condiciones difíciles bajo las cuales la gente vivía, comerciaba y viajaba; y muestra que la falta de una autoridad central causaba muchos problemas aun a los oficiales enviados por los diversos países, como en el caso mencionado de Egipto, país que anteriormente había desempeñado un poderoso papel en Palestina, pero que ahora estaba en decadencia.

- -

-

Barca de Keops,Giza

|

The Journey of Wenamon to Phoenicia

http://www.specialtyinterests.net/wenamon.html

Anet, 25-29

The papyrus, now in the Moscow Museum, comes from el_hibeh in Middle Egypt and dates to the early 21st Dynasty shortly after the events it relates.

Year 5, 4th month of the 3rd season, day 16:

the day on which Wenamon, the Senior of the Forecourt of the house of Amon, [lord of thrones] of the Two Lands, set out to fetch the woodwork for the great and august barque of Amon-Re, king of the gods, which is on [the river and which is named:] `User-het-Amon.’

On the day when I reached Tanis, the place [where Ne-su-Ba-neb]-Ded and Ta-net-Amon were [10], I gave them the letters of Amon-Re, king of … and they [20] had them read in their presence. And they said, “Yes, I will do as Amon-Re, king of gods, our [lord] has said!’

I spent up to the 4th month of the 3rd season in Tanis. And Ne-su-Ba-neb-Dad and Ta-net-Amon sent me off with the ship captain Mengebet. … and I embarked on the great Syrian sea in the 1st month of the 3rd season, day 1.

I reached Dor, a town of the Tjeker, and Beder, its prince, had 50 loaves of bread, one jug of wine [30], and one leg of beef brought to me. And a man of my ship ran away and stole on (vessel) of gold, [amounting] to 5 deben, four jars of silver, amounting to 20 deben, and a sack of 11 deben of silver. [Total of what] he [stole]:

5 deben of gold and 31 deben of silver. [40]

I got up in the morning, and I went up to the place where the Prince was, and I said to him: `I have been robbed in your harbor. Now you are the prince of this land, and you are its investigator who should look for my silver. Now about this silver - it belongs to Ne-su-Ba-neb-Ded; it belongs to Herihor, my lord, and the other great men of Egypt! It belongs to you; it belongs to Weret; it belongs to Mekmer; it belongs to Zakar-Baal, the prince of Byblos![50]

And he said unto me: `Whether you are important or whether you are eminent - look here, I do not recognize this accusation which you have made me! Suppose it had been a thief who belonged to my land who went on your boat and stole your silver, I should have repaid it to you from my treasury, until they had [60] found this thief of yours - whoever he may be. Now about the thief who robbed you - he belongs to you! He belongs to your ship! Spend a few days here visiting with me, so that I may look for him.’

I spent nine days moored (in) his harbor, and I went (to) call on him, and I said to him: `Look, you have not found my silver. [Just let] me [go] with the ship captains and with those who go (to) sea!’ But he said to me, `Be quiet! …’ …. I went out of Tyre at the break of down … Zakar-Baal, the prince of Byblos, …. (30) ship. I found 30 deben in it, and I seized upon it.(4) [And I said to the Tjeker: `I have seized upon] your silver, and it will stay with me [until] you find [my silver or the thief] who stole it. But as for you, …

So they went away, and I enjoyed my triumph [in] a tent [on] the shore of the [sea], [in] the harbor of Byblos. And [I hid] Amon-of-the-Road, and I put his property inside him.(5)

And the [prince] of Byblos send to me, saying: `Get [out of (35) my] harbor!’ And I sent him, saying: `Where should [I go to]? … If [you have a ship] to carry me, have me taken to Egypt again!’ So I spent 29 days in his [harbor, while] he [spent] the time sending to me every day to say: `Get out [of] my harbor!’

Now while he was making offering to his gods, the god - seized one of his youths and made him possessed.(6) And he said to him: `Bring up [the] god! Bring the messenger who is carrying him! (40) Amon is the one who sent him out! He is the one who made him come!’ And while the possessed youth was having a frenzy on this night, I had [already] found a ship headed for Egypt and had loaded everything that I had into it. While I was watching for the darkness, thinking that when it descended I would load the god [also], so that no other eye might see him, the harbor master came to me, saying: `Wait until morning - so says the prince.’ So I said to him: `Aren’t you the one who spent the time coming to me every day to say: `Get out [of] my harbor? Aren’t you saying, `Wait’ tonight (45) in order to let the ship which I had found get away - and [then] you will come again [to] say: `Go away!’?’

So he went and told it to the prince. And the prince sent to the captain of the ship to say: `Wait until morning - so says the prince!’

When morning came, he sent and brough me up, but the god stayed in the tent where he was, [on] the shore of the sea. And I found him sitting [in] his upper room, with his back turned to the window, so that the waves of the great Syrian sea broke against the back (50) of his head.(7)

So I said to him: `May Amon favor you!’ But he said to me: `How long, up to today, since you came from the palace where Amon is?’

So I said to him: `Five months and one day up to now,”

And he said to me: `Well, you’re truthful! Where is the letter of Amon which [should be] in your hand? Where is the dispatch of the high-priest of Amon which [should] be in your hand?’

And I told him: `I gave them to Ne-su-B-neb-ded and Ta-net-Amon.’

And he was very, very angry, and he said to me: `Now see - neither letters nor dispatches are in your hand! Where is (55) its Syrian crew? Didn’t he turn you over to his foreign ship captain to have him kill you and throw you into the sea? [Then] with whom would they have looked for you too? So he spoke to me.

But I said to him, `Wasn’t it an Egyptian ship?’ Now it is Egyptian crews which sail under Ne-su-Ba-neb-Ded! He has no Syrian crews.’

And he said to me: `Aren’t there 20 ships here in my harbor which are in commercial relations with Ne-su-Ba-neb-Ded? As to this Sidon, (ii,1) the other [place] which you have passed, aren’t there 50 more ships there which are in commercial relations with Werket-El, and which are drawn up to his house?’ And I was silent in this great time.

And he answered and said to me: `On what business have you come?’

So I told him: `I have come after the woodwork for the great and August bark of Amon-Re, king of gods. Your father did [it] (5), your grandfather did [it, and you will do it too!' So I spoke to him.

But he said to me: `To be sure, they did it! And if you give me something] for doing it, I will do it! Why, when my people carried out this commission, Pharaoh - life propserity, health! - sent six ships loaded with Egyptian goods, and they unloaded them into their storehouses! You - what is that you’re bringing me - me also?’

And he had the journal rolls of his father brought, and he had them read out in my presence, and they found a thousand deben of silver and all kinds of things in his scrolls.[100]

So he said to me: `If the ruler of Egypt where the lord of mine, and I were his servant also, he would not have send silver and gold, saying: `Carry out the commission of Amon!’ There would be no carrying of a royal gift, such as they used to do for my father. As for me - me also - I am not your servant! I am not the servant of him who sent me either! - If I cry out to the Lebanon, the heavens open up, and the logs are here lying [on] the shore of the sea! Give (15) me the sails which you have brought to carry your ships which would hold the logs for [Egypt]! Give me the ropes [which] you have brought [to lash the cedar] logs which I am cutting down to make you … which I shall make for you [as] the sails of your boats, and the spears will be [too] heavy and will break, and you will die in the middle of the sea! See, Amon made thunder in the sky when he put Seth near him.(8) Now when Amon (20) founded all lands, in founding them he founded first the land of Egypt, from which you come; for craftsmanship came out of it, to reach the place where I am. What are these silly trips which they have had you make?’

And I said to him: `[That's] not true! What I am on are no `silly trips’ at all! There is no ship upon the river which does not belong to Amon! The sea is his, and the Lebanon is his, of which you say: `It is mine!’ It forms (25) the nursery for User-het-Amon, the lord of [every] ship! Why, he spoke - Amon-Re, King of the gods - and said to Herihor, my master: `Send me forth!’ So he had me come, carrying this great god. But see, you have made this great god spend these 29 (days) moored [in] your harbor, although you did not know [it]. Isn’t he here? Isn’t he the [same] as he was? You are stationed [here] to carry on the commerce of the Lebanon with Amon, its lord. As for you saying that the former kings sent silver and gold - suppose they had life and health!(9) Now as for Amon-Re, king of the gods - he is the lord of this life and health, and he was the lord of your fathers. They spent their lifetime making offering to Amon. And you also - you are the servant of Amon! If you say to Amon: `Yes, I will do [it]!’ and you carry out his commission, you will live, you will be prosperous, you will be healthy, and you will be good to your entire land and your people! [But] don’t wish for yourself anything belonging to Amon-Re, [king of] the gods. Why, a lion wants his own property! Have your secretary brought to me, so that (35) I may send him to Ne-su-Ba-neb-Ded and Ta-net-Amon, the officers whom Amon put in the north of his land, and they will have all kinds of things sent. I shall send him to them to say: `Let it be brought until I shall go [back again] to the south, and I shall [then] have every bit of the dept still [due to you] brought to you.’ So I spoke to him.

So he entrusted my letter to his messenger, and he loaded in the keel, the bow post, the stern post, along with our four other hewn timbers - seven in all - and he had them taken to Egypt. And in the first month of the second season his messenger who had gone to Egypt came back to me in Syria. And in the first month of the second season he messenger sho had gone to Egypt came back to me in Syria. And Ne-su-Ba-neb-Ded and Ta-net-Amon sent: (40)

4 jars and 1 kakmen of gold;

5 jars of silver;

10 pieces of clothing in royal linen;

500 kherd of good Upper Egyptian linen;

500 cowhides;

500 ropes;

20 sacks of lentils;

30 baskets of fish;

And he sent to me [personally]:

5 pieces of clothing in good Upper Egyptian linen;

5 kherd of good Upper Egyptian linen;

1 sack of lentils;

5 baskets of fish;

And the prince was glad, and he detailed three hundred men and three hundred cattle, and he put supervisors at their head, to have them cut down the timber. So they cut them down, and they spend the second season lying there.(10)

In the 3rd month of the 3rd season they dragged them [to] the shore of the sae, and the prince came out and stood by them. And he sent to me, saying: `Come!’ Now when I presented myself near him, the shadow of his lotus - blossom fell upon me. And Pen-Amon, a butler who belonged to him, cut me off, saying: `The shadow of Pharaoh - lief, prosperity, health! - your lord, has fallen on you!’ But he was angry at him, saying: `Let him alone.’(11)

So I presented myself near him, and he answered and siad to me: `See, the commission which my fathers carried out formerly, I have carried it out [also], even though you have not done for me what your fathers would have done for me, and you too [should have done]! See, the last of your woodwork has arrived and is lying [here]. Do as I wish, and come to load it in - for aren’t they going to give it it you?(50) Don’t come to look at the terror of the sae! If you look at the terror of the sea, you will see my own [too].’(12) Why, I have not done to you what was done to the messengers of Kha-em-Wasert, when they spent seventeen years in this land - they died [where] they were!’ And he said to his butler: `Take him and show him their tomb in which they are lying.’

But I said to him: `Don’t show it to me! As for Kha-em-Waset - they were men whom he send to you as messengers, and he was a man himself. You do not have one of his messengers [here in me], when you say: `Go and see you companions!’

Now shouldn’t you rejoice (55) and have a stela [made] for yourself and say on it: `Amon-Re, king of the gods, sent to me Amon-of-the-Road, his messenger - [life], prosperity, health! - and Wenalmon, his human messenger, after the woodwork for the great and August barque of Amon-Re, king of the gods. I cut it down. I loaded it in. I provided it [with] my ships and my crews. I caused them to reach Egypt, in order to ask fifty years of life from Amon for myself, over and aboce my fate.’ And it shall come to pass that, after another time, a messenger may come from the land of Egypt who knows writing, and he may read your name on the stela. And you will receive water [in] the West, like the gods who are (60) here!’(13)

And he said to me: `This which you have said to me is great testimony of words!’(14)

So I said to him: `As for the many things which you have said to me, if I reach the place where the high priest of Amon is and he sees how you have [carried out his] commission, it is your [carrying out of this] commission [which] will draw out something for you.’

And I went [to] the shore of the sea, to the place where the timber was lying, and I spied 11 ships belonging to the Tjeker coming in from the sea, in order to say: `Arrest him! Don’t let a ship of his [go] to the land of Egypt!’ Then I set down and wept. And the letter scribe of the prince came out to me,(65) and he said to me: `What’s the matter with you?’ And I said to him: `Haven’t you seen the birds go down to Egypt a second time?(15) Look at them - how they travel to the cool pools! [But] how long shall I be left here! Now don’t you see those who are coming again to arrest me?’

So he went and told it to the prince. And the prince began to weep because of the words which were said to him, for they were painful. And he sent out to me his letter scribe, and he brought to me 2 jugs of wine and one ram. And he sent to me Ta-net-Not, an Egyptian singer was with him,(16) saying: `Sing to him! Don’t let his heart take on cares!’ And he sent to me,(70) to say: `Eat and drink! Don’t let your heart take on cares, for tomorrow you shall hear whatever I have to say.’

When morning came, he had his assembly summond, and stood in their midst, and he said to the Tjeker: `What have you come [for]?’ and they said to him: `We have come after the [blasted] ships which you are sending to Egypt with your opponents!’ But he said to them: `I cannot arrest the messenger of Amon inside my land. Let me send him away, and you go after him to arrest him.’

So he loaded me in, and he sent me away from there at the harbor of the sea. And the wind casts me on the land of (75) Alashiya. And they of the town came out against me to kill me, but I forced my way through them to the place where Hetep, the princess of the town, was. I met her as she was going out of one house of hers and going into another of hers.

So I greeted her, and I said to the people who were standing near her: `Isn’t there one of you who understands Egyptian?’ And one of them said: `I understand [it].’ So I said to him: `Tell the lady that I have heard, as far away as Thebes, the place where Amon is, that injustice is done in every town but justice is done in the land of Alishiya. Yet, injustice is done here every day!’ And she said: `Why, what do you [mean] (80) by saying it?’ So I told her: `If the sea is stormy and the wind casts me on the land where you are, you should not let them take me [in charge] to kill me. For I am a messenger of Amon. Look here - as for me, they will search for me all the time! As to this crew of the Prince of Byblos which they are bent on killing, won’t its lord find ten crews of yours, and he also kill them?’

So she had the people summoned, and they stood [there]. And she said to me: `Spend the night …’

[At this point the papyrus breaks off. Since the tale is told in the first person, it is fair to assume that Wenamon returned to Egypt to tell his story, in some measure of safety or success.]

The Basest of the Kingdoms

Since the days of the Persian conquest under Cambyses, Egypt had been `the basests of the kingdoms’, Ezekiel 29:15. The prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel concerning the debasement of Egypt were fulfilled, not in their time, but at the close of Amasis’ reign, when Cambyses subjugated Egypt, humiliated its people, and ruined its temples, and for generations thereafter, through most of the Persian period.

When Golenishchev purchased the papyrus with Ourmai’s letter of laments, he obtained in the same transaction a papyrus containing another tale of woe - the story of Wenamon’s errand to Byblose on the coast of Syria. Like the letter of Ourmai, the above story of Wenamon dates from the 21st Dynasty; both were copied by the same scribe, but it is understood that Wenamon’s story relates events several generations more recent. Whereas Ourmai’s letter was translated and published in 1961, Wenamon’s story was published in 1899.

No document pictures Egypt’s lowly position among the nations during the later period of Persian occupation better than does Wenamon’s story.

During the time under discussion, traveling in Syria was filled with danger, Nehemia [2:7] and Ezra [8:22](17) both mention the insecurity of the roads, even for one on the king’s errand.

Picking up on the important clues in the story

It is of interest that quite a number of Hebrew words are used by Wenamon in his story: For `assembly’ he used the Hebrew word `moed’ and for `league’ or `alliance’ the word `hever’; other such instances of preferrence given to Hebrew words over Egyptian vocabulary are exhibited by Wenamon.

Two names in the text caused deliberation among scholars. One was Khaemwise (Kha-em-waset), in whose days messengers sent from Egypt were detained in Byblose against their will. The other was the name of the ship owner Werket-El or Birkath-El, who maintained commercial traffic between Sidon and Tanis.

No answer was found to the question of the identity of Khaemwise. Ramses IX or Neferkare-setpenre Ramesse-khaemwise-merer-amon and Ramses XI or Menmare-sepenptah Ramesse-khaemwise were considered bu rejected. Khaemwise was certainly a king’ (18) but, Ramses IX and Ramses XI having reigned only very recently, Wenamon, a priest and official, would not omit in referring to either of them the title `king’ - such titling being a matter of civility a priest and scribe would no violate.(19)

The other name found in the Wenamon Papyrus that caused deliberation is that of the shipping magnate with headquarters in Tanis. Of him the prince of Byblos said that in Sidon 50 ships `are in league’ with Birketh-El’ and sail `to his house.’

The eminent German Egyptologist read his name Birket-El to which M. Burchardt agreed. The name points to a semitic origin, most likely a Phoenician. It means `God’s blessing.’

In 1924, R. Eisler published a paper, `Barakhel Sohn und Cie, Rhedergesellschaft in Tanis’ (Barkhal Son & Co., Shipping House in Tanis)(20) in which he drew attention to the fact that a late Hebrew source contains a reference to the same shipping company called Berakhel’s Son.

The Testament of Naphthali is a pseudoepigraphic work the composition of which is placed in about 146 BC, the year Johnathan of the House of Hasshmnaim (Maccabees) conquered Jaffa and thus opened an access to the sea and maritime trade.

In the testament, a vision is narrated of a ship that passes near the shore of Jaffa with no crew or passengers. But on the mast of the ship is written the name of the owner, son of Berakhel. Berakhel and Birketh-El relate to each other like `God’s blessing’ and `blessing of God’ would in English.

In our estimate, Wenamon went on his travels not in 1100 BC but close to about 400 BC. |

|

|

Notes & References[0010] The identity of Nesubanebded and Tanetamon are not known as far as we know. Please be aware that some numbers in ( ) and [] were in the original text and do are not references from us.

[0020] Tanis was the capital of Egypt for much of that country’s time. Please check the Encyclopedia for comments on it. Also read the article on pottery.

[0030] Please check the Encyclopedia for info on the Tjeker and Dor. A prince named `Beder’ is not known from other sources as far as we know.

[0040] Compare the measures of quantity with our file on the Great Edict.

[0050] Again, on Weret and Mekmer we have no additional information. On Zerket-Baal and Byblos check the Encyclopedia.

[0060] Check also the EA letters for certain nouns and terms.

[0100] No comment at this time. |

|

THE HISTORY OF THE PHILISTINES

http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/phc/phc04.htm

Web del Museo Puskhin,Moscú(Col.Papiros)

http://www.trismegistos.org/tm/detail.php?tm=90154

http://www.trismegistos.org/coll/collref_list.php?tm=234&partner=tm

http://www.trismegistos.org/index.html

TRISMEGISTOS An interdisciplinary portal of papyrological and epigraphical resources

dealing with Egypt and the Nile valley between roughly 800 BC and AD 800

I. The Adventures of Wen-Amon among them

The Golénischeff papyrus 1 was found in 1891 at El-Khibeh in Upper Egypt. It is the personal report of the adventures of an Egyptian messenger to Lebanon, sent on an important semi-religious, semi-diplomatic mission. The naïveté of the style makes it one of the most vivid and convincing narratives that the ancient East affords.

Ramessu III is nominally on the throne, and the papyrus is dated in his fifth year. The real authority at Thebes is, however, Hrihor, the high priest of Amon, who is ultimately to usurp the sovereignty and become the founder of the Twenty-first Dynasty. In Lower Egypt, the Tanite noble Nesubenebded, in Greek Smendes, has control of the Delta. Egypt is in truth a house divided against itself.

On the sixteenth day of the eleventh month of the fifth year of Ramessu, one Wen-Amon was dispatched from Thebes to fetch timber for the barge called User-het, the great august sacred barge of Amon-Ra, king of the gods. Who Wen-Amon may have been, we do not certainly know; he states that he had a religious office, but it is not clear what this was. It speaks eloquently for the rotten state of Egypt at the time, however, that no better messenger could be found than this obviously incompetent person—a sort of Egyptian prototype of the Rev. Robert Spalding! With him was an image of Amon, which he looked upon as a kind of fetish, letters of credit or of introduction, and the wherewithal to purchase the timber.

Sailing down the Nile, Wen-Amon in due time reached Tanis, and presented himself at the court of Nesubenebded, who with his wife Tentamon, received the messenger of Amon-Ra with fitting courtesy. He handed over his letters, which (being themselves unable to decipher them) they caused to be read: and they said, ‘Yea, yea,

p. 30

[paragraph continues] I will do all that our lord Amon-Ra saith.’ Wen-Amon tarried at Tanis till a fortnight had elapsed from his first setting out from Thebes; and then his hosts put him in charge of a certain Mengebti, captain of a ship about to sail to Syria. This was rather casual; evidently Mengebti’s vessel was an ordinary trading ship, whereas we might have expected (and as appears later the Syrians did expect) that one charged with an important special message should be sent in a special ship. At this point the thoughtless Wen-Amon made his first blunder. He forgot all about reclaiming his letters of introduction from Nesubenebded, and so laid up for himself the troubles even now in store for the helpless tourist who tries to land at Beirut without a passport. Like the delightful pilgrimage of the mediaeval Dominican Felix Fabri, the modernness of this narrative of antiquity is not one of its least attractions.

On the first day of the twelfth month Mengebti’s ship set sail. After a journey of unrecorded length the ship put in at Dor, probably the modern Tantura on the southern coast of the promontory of Carmel. Dor was inhabited by Zakkala (a very important piece of information) and they had a king named Badyra. We are amazed to read that, apparently as soon as the ship entered the harbour, this hospitable monarch sent to Wen-Amon ‘much bread, a jar of wine, and a joint of beef’. I verily believe that this was a tale got up by some bakhshish-hunting huckster. The simpleminded tourist of modern days is imposed upon by similar magnificent fables.

There are few who have travelled much by Levant steamers without having lost something by theft. Sufferers may claim Wen-Amon as a companion in misfortune. As soon as the vessel touched at Dor, some vessels of gold, four vessels and a purse of silver—in all 5 deben or about 1 1/5 lb. of gold and 31 deben or about 7½ lb. of silver—were stolen by a man of the ship, who decamped. This was all the more serious, because, as appears later, these valuables were actually the money with which Wen-Amon had been entrusted for the purchase of the timber.

So Wen-Amon did exactly what he would have done in the twentieth century AḌ. He went the following morning and interviewed the governor, Badyra. There was no Egyptian consul at the time, so he was obliged to conduct the interview in person. ‘I have been robbed in thy harbour,’ he says, ‘and thou, being king, art he who should judge, and search for my money. The money indeed belongs to Amon-Ra, and Nesubenebded, and Hrihor my lord: it also belongs to Warati, and Makamaru, and Zakar-Baal prince of Byblos’

p. 31

[paragraph continues] —the last three being evidently the names of the merchants who had been intended to receive the money. The account of Abraham’s negotiations with the Hittites is not more modern than the king’s reply. We can feel absolutely certain that he said exactly the words which Wen-Amon puts in his mouth: ‘Thy honour and excellency! Behold, I know nothing of this complaint of thine. If the thief were of my land, and boarded the ship to steal thy treasure, I would even repay it from mine own treasury till they found who the thief was. But the thief belongs to thy ship (so I have no responsibility). Howbeit, wait a few days and I will seek for him.’ Wen-Amon had to be content with this assurance. Probably nothing was done after he had been bowed out from the governor’s presence: in any case, nine days elapsed without news of the missing property. At the end of the time Wen-Amon gave up hope, and made up his mind to do the best he could without the money. He still had his image of Amon-Ra, and he had a child-like belief that the foreigners would share the reverent awe with which he himself regarded it. So he sought permission of the king of Dor to depart.

Here comes a lacuna much to be deplored. A sadly broken fragment helps to fill it up, but consecutive sense is unattainable. ‘He said unto me “Silence!” . . . and they went away and sought their thieves . . . and I went away from Tyre as dawn was breaking . . . Zakar-Baal, prince of Byblos. . . there I found 30 deben of silver and took it . . . your silver is deposited with me . . . I will take it . . . they went away . . . I came to . . . the harbour of Byblos and . . . to Amon, and I put his goods in it. The prince of Byblos sent a messenger to me . . . my harbour. I sent him a message . . .’ These, with a few other stray words, are all that can be made out. It seems as though Wen-Amon tried to recoup himself for his loss by appropriating the silver of some one else. At any rate, the fragment leaves Wen-Amon at his destination, the harbour of Byblos. Then the continuous text begins again. Apparently Zakar-Baal has sent a message to him to begone and to find a ship going to Egypt in which he could sail. Why Zakar-Baal was so inhospitable does not appear. Indeed daily, for nineteen days, he kept sending a similar message to the Egyptian, who seems to have done nothing one way or another. At last Wen-Amon found a ship about to sail for Egypt, and made arrangements to go as a passenger in her, despairing of ever carrying out his mission. He put his luggage on board and then waited for the darkness of night to come on board with his image of Amon, being for some reason anxious that none but himself should see this talisman.

p. 32

But now a strange thing happened. One of the young men of Zakar-Baal’s entourage was seized with a prophetic ecstasy—the first occurrence of this phenomenon on record—and in his frenzy cried, Bring up the god! Bring up Amon’s messenger that has him! Send him, and let him go.’ Obedient to the prophetic message Zakar-Baal sent down to the harbour to summon the Egyptian. The latter was much annoyed, and protested, not unreasonably, at this sudden change of attitude. Indeed he suspected a ruse to let the ship go off; with his belongings, and leave him defenceless at the mercy of the Byblites. The only effect of his protest was an additional order to ‘hold up’ the ship as well.

In the morning he presented himself to Zakar-Baal. After the sacrifice had been made in the castle by the sea-shore where the prince dwelt, Wen-Amon was brought into his presence. He was ’sitting in his upper chamber, leaning his back against a window, while the waves of the great Syrian sea beat on the shore behind him’. To adapt a passage in one of Mr. Rudyard Kipling’s best-known stories, we can imagine the scene, but we cannot imagine Wen-Amon imagining it: the eye-witness speaks in every word of the picturesque description.

The interview was not pleasant for the Egyptian. It made so deep an impression upon him, that to our great gain he was able when writing his report to reproduce it almost verbatim, as follows:

‘Amon’s favour upon thee,’ said Wen-Amon.

‘How long is it since thou hast left the land of Amon?’ demanded Zakar-Baal, apparently without returning his visitor’s salutation. ‘Five months and one day,’ said Wen-Amon.

(This answer shows how much of the document we have lost. We cannot account for more than the fourteen days spent between Thebes and Tanis, nine days at Dor, nineteen days at Byblos—six weeks in all-plus the time spent in the voyage, which at the very outside could scarcely have been more than another six weeks.)

‘Well then, if thou art a true man, where are thy credentials?’

We remember that Wen-Amon had left them with the prince of Tanis, and he said so. Then was Zakar-Baal very wroth. ‘What! There is no writing in thy hand? And where is the ship that Nesubenebded gave thee? Where are its crew of Syrians? For sure, he would never have put thee in charge of this (incompetent Egyptian) who would have drowned thee—and then where would they have sought their god and thee?’

This is the obvious sense, though injured by a slight lacuna. Nothing more clearly shows how the reputation of Egypt had sunk

p. 33

in the interval since the exploits of Ramessu III. Zakar-Baal speaks of Mengebti and his Egyptian crew with much the same contempt as Capt. Davis in Stevenson’s Ebb-tide speaks of a crew of Kanakas. Wen-Amon ventured on a mild protest. ‘Nesubenebded has no Syrian crews: all his ships are manned with Egyptians.’

‘There are twenty ships in my harbour,’ said Zakar-Baal sharply, and ten thousand ships in Sidon—’ The exaggeration and the aposiopesis vividly mirror the vehemence of the speaker. He was evidently going on to say that these ships, though Egyptian, were all manned by Syrians. But, seeing that Wen-Amon was, as he expresses it, ’silent in that supreme moment’ he broke off, and abruptly asked—

‘Now, what is thy business here?’

We are to remember that Wen-Amon had come to buy timber, but had lost his money. We cannot say anything about whether he had actually recovered the money or its equivalent, because of the unfortunate gap in the document already noticed. However, it would appear that he had at the moment no ready cash, for he tried the effect of a little bluff. ‘I have come for the timber of the great august barge of Amon-Ra, king of the gods. Thy father gave it, as did thy grandfather, and thou wilt do so too.’

But Zakar-Baal was not impressed. ‘True,’ said he, ‘they gave the timber, but they were paid for it: I will do so too, if I be paid likewise.’ And then we are interested to learn that he had his father’s account-books brought in, and showed his visitor the records of large sums that had been paid for timber. ‘See now,’ continued Zakar-Baal in a speech rather difficult to construe intelligibly, ‘had I and my property been under the king of Egypt, he would not have sent money, but would have sent a command. These transactions of my father’s were not the payment of tribute due. I am not thy servant nor the servant of him that sent thee. All I have to do is to speak, and the logs of Lebanon lie cut on the shore of the sea. But where are the sails and the cordage thou hast brought to transport the logs? . . . Egypt is the mother of all equipments and all civilization; how then have they made thee come in this hole-and-corner way?’ He is evidently still dissatisfied with this soi-disant envoy, coming in a common passenger ship without passport or credentials.

Then Wen-Amon played his trump card. He produced the image of Amon. ‘No hole-and-corner journey is this, O guilty one!’ said he. ‘Amon owns every ship on the sea, and owns Lebanon which thou hast claimed as thine own. Amon has sent me, and Hrihor my lord has made me come, bearing this great god. And yet, though thou didst

p. 34

well know that he was here, thou hadst kept him waiting twenty-nine days in the harbour. 1 Former kings have sent money to thy fathers, but not life and health: if thou do the bidding of Amon, he will send thee life and health. Wish not for thyself a thing belonging to Amon-Ra.’

These histrionics, however, did not impress Zakar-Baal any more than the previous speech. Clearly Wen-Amon saw in his face that the lord of Byblos was not overawed by the image of his god, and that he wanted something more tangible than vague promises of life and health. So at length he asked for his scribe to be brought him that he might write a letter to Tanis, praying for a consignment of goods on account. The letter was written, the messenger dispatched, and in about seven weeks returned with a miscellaneous cargo of gold, silver, linen, 500 rolls of papyrus (this is important), hides, rope, lentils, and fish. A little present for Wen-Amon himself was sent as well by the lady Tentamon. Then the business-like prince rejoiced, we are told, and gave the word for the felling of the trees. And at last, some eight months after Wen-Amon’s departure from Thebes, the timber lay on the shore ready for delivery.

A curious passage here follows in the papyrus. It contains one of the oldest recorded jokes—if not actually the oldest—in the world. When Zakar-Baal came down to the shore to give the timber over to Wen-Amon, he was accompanied by an Egyptian butler, by name Pen-Amon. The shadow of Zakar-Baal’s parasol happened to fall on the envoy, whereupon the butler exclaimed, ‘Lo, the shadow of Pharaoh thy lord falleth on thee!’ The point of the witticism is obscure, but evidently even Zakar-Baal found it rather too extreme, for he sharply rebuked the jester. But he proceeded himself to display a delicate humour. ‘Now,’ said he, ‘I have done for thee what my fathers did, though thou hast not done for me what thy fathers did. Here is the timber lying ready and complete. Do what thou wilt with it. But do not be contemplating the terror of the sea’ (there cannot be the slightest doubt that Wen-Amon was at this moment glancing over the waters and estimating his chances of a smooth crossing). ‘Contemplate for a moment the terror of Me! Ramessu IX sent some messengers to me and’—here he turned to the butler—’ Go thou, and show him their graves!’

‘Oh, let me not see them!’ was the agonized exclamation of Wen-Amon, anxious now above all things to be off without further delay. Those were people who had no god with them! Wherefore dost thou not instead erect a tablet to record to all time “that Amon-Ra

p. 35

sent to me and I sent timber to Egypt, to beseech ten thousand years of life, and so it came to pass”?’

‘Truly that would be a great testimony!’ said the sarcastic prince, and departed.

Wen-Amon now set about loading his timber. But presently there sailed eleven ships of the Zakkala into the harbour—possibly those on whom he had made a rash attempt at piracy to recoup himself for his losses at Dor. The merchants in them demanded his arrest. The poor Egyptian sat down on the shore and wept. ‘They have come to take me again!’ he cried out—it would appear that he had been detained by the Zakkala before, but the record of this part of his troubles is lost in one of the lacunae of the MS. We despair of him altogether when he actually goes on to tell us that when news of this new trouble reached Zakar-Baal, that magnate wept also. However, we need not question the charming detail that he sent to Wen-Amon an Egyptian singing-girl, to console him with her songs. But otherwise he washed his hands of the whole affair. He told the Zakkala that he felt a delicacy about arresting the messenger of Amon on his own land, but he gave them permission to follow and arrest him themselves, if they should see fit. So away Wen-Amon sailed, apparently without his timber, and presumably with the Zakkala in pursuit. But he managed to evade them. A wind drove him to Cyprus. The Cypriotes came out, as he supposed, to kill him and his crew; but they brought them before Hatiba, their queen. He called out ‘Does any one here understand Egyptian?’ One man stepped forward. He dictated a petition to be translated to the queen—

And here the curtain falls abruptly, for the papyrus breaks off; and the rest of this curious tragi-comedy of three thousand years ago is lost to us.

We see from it that the dwellers on the Syrian coast had completely thrown off the terror inspired by the victories of Ramessu III. An Egyptian on a sacred errand from the greatest men in the country, bearing the image of an Egyptian god, could be robbed, bullied, mocked, threatened, thwarted in every possible way. Granted that he was evidently not the kind of man to command respect, yet the total lack of reverence for the royalties who had sent him, and the sneers at Egypt and the Egyptian rulers, are very remarkable.

We see also that the domain of the ‘People of the Sea’ was more extensive than the scanty strip of territory usually allowed them on Bible maps. Further evidence of this will meet us presently,

p. 36

but meanwhile it may be noted that the name ‘Palestine’ is much less of an extension of the name ‘Philistia’ than the current maps would have us suppose. In other words, the two expressions are more nearly synonymous than they are generally taken to be. We find Dor, south of Carmel, to be a Zakkala town; and Zakkala ships are busy in the ports further north.

Indeed, one is half inclined to see Zakkala dominant at Byblos itself. Wen-Amon was a person of slender education—even of his own language he was not a master—and he was not likely to render foreign names correctly. Probably he could speak nothing but Egyptian: he was certainly ignorant of the language of Cyprus, whatever that may have been: and possibly linguistic troubles are indicated by his rendering of the name of the lord of Byblos. Can it be that this was not a name at all, but a title (or rather the Semitic translation of a title, given by a Zakkala dragoman): that Zakar is not זכר ‘remember’, but the name of the Zakkala: and that Baal here, as frequently elsewhere, means ‘lord’ in a human and not a divine sense? If so, the name would mean ‘the lord of the Zakkala’, a phrase that recalls ‘the lords of the Philistines’ in the Hebrew Scriptures. The syntax assumed is of course quite un-Semitic: but it is often the case in dragomans’ translations that the syntax of the original language is preserved. Something like this idea has been anticipated by M. A. J. Reinach. 1

Zakar-baal was no mere pirate chieftain, however. He was a substantial, civilized, and self-reliant prince, and contrasts most favourably with the weak, half-blustering, half-lacrimose Egyptian. He understood the Egyptian language; for he could rebuke the jest of his Egyptian butler, who would presumably speak his native tongue in ‘chaffing’ his compatriot; and no doubt the interview in the upper room was carried on in Egyptian. He was well acquainted with the use of letters, for he knew where to put his finger on the relevant parts of the accounts of his two predecessors. These accounts were probably not in cuneiform characters on clay tablets, as he is seen to import large quantities of papyrus from Egypt. He is true to his old maritime traditions: he builds his house where he can watch the great waves of the Mediterranean beat on the shore, and he is well informed about the ships in his own and the neighbouring harbours, and their crews.

There is a dim recollection of a Philistine occupation of Phoenicia

p. 37

recorded for us in an oft-quoted passage of Justin (xviii. 3. 5), 1 in which he mentions a raid by the king of Ashkelon, just before the fall of Troy, on the Phoenician town of Sidon (so called from an alleged Phoenician word ‘Sidon’, meaning ‘fish’). ‘This is of course merely a saga-like tradition, and as we do not know from what authority Justin drew his information we can hardly put a very heavy strain upon it. And yet it seems to hang together with the other evidence, that in the Mycenaean period, when Troy was taken, there actually was a Philistine settlement on the Phoenician coast. As to the specific mention of Ashkelon, a suggestion, perhaps a little venturesome, may be hazarded. The original writer of the history of this vaguely-chronicled event, whoever he may have been, possibly recorded correctly that it was the Zakkala who raided Sidon. Some later author or copyist was puzzled by this forgotten name, and ‘emended’ a rege Sacaloniorum to a rege Ascaloniorum. Stranger things have happened in the course of manuscript transmission. 2

The Papyrus gives us some chronological indications of importance. The expedition of Wen-Amon took place in the fifth year of Ramessu XII, that is to say, about 1110 B.C. Zakar-Baal had already been governor of Byblos for a considerable time, for he had received envoys from Ramessu IX (1144–1129). Suppose these envoys to have come about 1130, that gives him already twenty years. The envoys of Ramessu IX were detained seventeen years; but in the first place this may have been an exaggeration, and in the second place we need not suppose that many of those seventeen years necessarily fell within the reign of the sender of these messengers. Further, Zakar-Baal’s father and grandfather had preceded him in office. We do not know how long they reigned, but giving twenty-five years to each, which is probably a high estimate, we reach the date 1180, which is sufficiently long after the victory of Ramessu III for the people to begin to recover from the blow which that event inflicted on them.

Footnotes

29:1 See Max Müller, Mittheilungen der deutschen vorderasiatischen Gesellschaft, 1900, p. 14; Erman, Zeitschrift far ägyptische Sprache, xxxviii, p. 1; Breasted, Ancient Records, iv, p. 274.

34:1 An inconsistency: he has added ten days to his former statement.

36:1 ‘Byblos, où règne un prince qui pourrait bien être un Tchakara sémitisé, si l’on en croit son nom de Tchakar-baal.’ Revue archéologique, sér. IV, vol. xv, p. 45.

37:1 ‘Et quoniam ad Carthaginiensium mentionem uentum est, de origine eorum pauca dicenda sunt, repetitis Tyriorum paulo altius rebus, quorum casus etiam dolendi fuerunt. Tyriorum gens condita a Phoenicibus fuit, qui terraemotu uexati, relicto patriae solo, Assyrium stagnum primo, mox mari proximum littus incoluerunt, condita ibi urbe quam a piscium ubertate Sidona appellauerunt; nam piscem Phoenices sidon uocant. Post multos deinde annos a rege Ascaloniorum expugnati, nauibus appulsi, Tyron urbem ante annum Troianae cladis condiderunt.’

37:2 On the other hand Scylax in his Periplus calls Ashkelon ‘a city of the Tyrians’.

-

-

Últimos comentarios