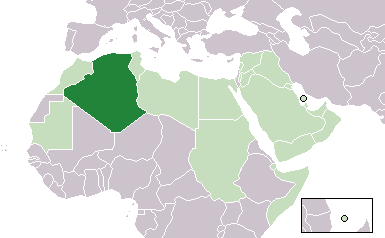

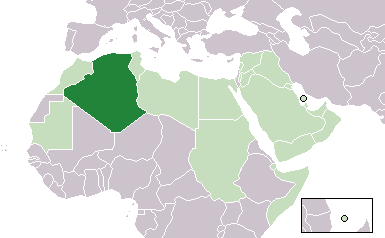

La República Argelina Democrática y Popular o Argelia, es un país del norte de África perteneciente al Magreb. Siendo el segundo país en superficie de África, limita con el Mar Mediterráneo al norte, Túnez al noreste, Libia al este, Níger al sudeste, Malí y Mauritania al suroeste, y Marruecos y el Sáhara Occidental al oeste.

Constitucionalmente se define como país árabe, bereber (amazigh) y musulmán. Es miembro de la Unión Africana y de la Liga Árabe desde prácticamente su independencia, y contribuyó a la creación de la Unión del Magreb Árabe (UMA) en 1988.

L’Algérie (arabe : الجزائر, tamazight: Dzayer en tifinagh :ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ), officiellement la République algérienne démocratique et populaire, est un État d’Afrique du Nord qui fait partie du Maghreb. Sa capitale, Alger, est située au nord, sur la côte méditerranéenne. Avec une superficie de 2 381 741 km², c’est le plus grand pays bordant la Méditerranée et le deuxième plus étendu d’Afrique après le Soudan. Il partage des frontières terrestres au nord-est avec la Tunisie, à l’est avec la Libye, au sud avec le Niger et le Mali, au sud-ouest avec la Mauritanie et le territoire contesté du Sahara occidental, et à l’ouest avec le Maroc.

L’Algérie est membre de l’Organisation des Nations unies (ONU), de l’Union africaine (UA) et de la Ligue des États arabes pratiquement depuis son indépendance, en 1962. Elle a intégré l’Organisation des pays exportateurs de pétrole (OPEP) en 1969. En février 1989, l’Algérie a pris part, avec les autres États maghrébins, à la création de l’organisation de l’Union du Maghreb arabe (UMA).

La Constitution algérienne définit « l’islam, l’arabité et l’amazighité » comme « composantes fondamentales » de l’identité du peuple algérien et le pays comme « terre d’Islam, partie intégrante du Grand Maghreb, méditerranéen et africain »[5].

Antigüedad

Argelia ha estado habitada por los bereberes desde hace más de diez mil años. Desde el año 1000 a. C. hay constancia de que éstos mantenían relaciones comerciales con los cartagineses, que habían construido colonias en la costa, y con los egipcios. En el siglo III a. C., los romanos denominan esta región Numidia, habitada por los bereberes masilianos y los maselinos. Éstos últimos se aliaron con los cartagineses en la Segunda Guerra Púnica, mientras que los primeros, aliados de los romanos y gobernados por Masinisa, acabaron recibiendo todo el reino de sus conquistadores.

— — — — — —

Retrato moderno de Masinisa, el león del Atlas

(c.241-148): king of the Massylians in Numidia (202-148)

Masinisa (c. 238 a. C. - c. 148 a. C.) king of the Massylians in Numidia (202-148).fue el primer rey de Numidia, con capital en Cirta, hoy Constantina (Argelia). Rigió sobre su propia tribu, los Maesilos, y la de los Masessilos, originalmente liderados por el pro-cartaginés Sifax. Comenzó como líder tribal de los bereberes, sucediendo a su padre Gaia. Aliado de Cartago, junto al general Asdrúbal Giscón derrotó al númida Sifax cuando contaba con tan sólo con 17 años (213 a. C. ó 212 a. C.). Luchó como aliado de Cartago en Hispania, dirigiendo a sus jinetes númidas y finalmente liderando una exitosa campaña de guerrilla contra los romanos.

Vuelta a Numidia

Tras regresar a su reino, sostuvo varias guerras civiles contra los régulos Sifax, Lacumazes y Mazetulo. Derrotado por Sifax, fue perseguido por uno de los generales de éste, Búcar, pero reunió un nuevo ejército. En una nueva batalla, el hijo de Sifax, Vermina, decidió la batalla a favor de su padre.

Exiliado por un tiempo, alrededor del 206 a. C. comenzó a cooperar con los romanos (según parece conocía personalmente a Lelio, comandante de caballería de Escipión), luchando a su lado en la Batalla de Zama (cercana a la ciudad actual de Maktar, Túnez). Durante la batalla, mientras la infantería cartaginesa se enfrentaba con relativo éxito a las legiones romanas bajo el mando de Escipión el Africano, la caballería de Masinisa había abandonado la batalla en persecución de la cartaginesa. Tras su regreso, los romanos consiguieron derrotar a los veteranos y levas dirigidas por Aníbal.

Rey de Numidia

Roma respaldó su recién fundado reino de Numidia, al oeste de Cartago. Esto convenía a los intereses latinos, dado que sus nuevos vecinos traerían más problemas a Cartago. Bajo el mando de Masinisa muchas de las tribus seminómadas se convirtieron en campesinos y granjeros. Sin embargo, aún había pocas áreas urbanizadas.

A lo largo de su vida, Masinisa extendió el reino, colaborando con Roma. Hacia el final de su vida, provocó a Cartago para que le declarase la guerra. Según Livio, los númidas comenzaron a saquear alrededor de 70 ciudades en las fronteras sur y oeste de Cartago. Airados por esta conducta, los cartagineses declararon la guerra a Masinisa, desafiando el tratado firmado tras la Segunda Guerra Púnica que prohibía a Cartago declarar la guerra a una tercera nación. El resultado fue la tercera y última guerra púnica. Antiguos textos indican que Masinissa vivió durante más de 90 años, y aparentemente seguía dirigiendo personalmente a sus ejércitos cuando murió.

Tras su muerte, Numidia fue dividida en varios pequeños reinos al cargo de sus hijos.

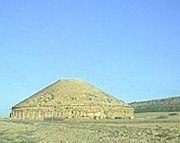

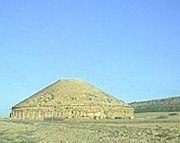

Tumba de Masinisa,cerca de Constantina,Argelia

Livius.org: Massinissa

When Massinissa was born, Numidia (more or less the north of modern Algeria) was a country on the edge of the urbanized world of the Mediterranean. Although many people were living in large villages that would eventually develop into cities, another part of the Numidian population was still roaming over the plains. Our word “nomad” is derived from “Numidia”.

There were two tribal federations, both in the process of becoming full-blown kingdoms. In the west lived the Masaeisylians, in the east the Massylians. (They are already confused in ancient sources.) It seems that the eastern kingdom, which was close to Carthage, was more sympathetic to this city, and it is possible that the Carthaginians had actively encouraged the rise of a pro-Carthaginian dynasty that would be a buffer against the western Numidians.

Massinissa was the son of king Gala (or Gaïa) of the Massylians, and was educated in Carthage - a kind way to say that he was in fact a hostage. In 212, when he was almost thirty years old, he served as commander of a Numidian cavalry unit in the Carthaginian army in Iberia. These were the years of the Second Punic War (218-202), in which Hannibal was fighting in Italy against the Romans. At the same time, the Romans tried to conquer Hispania, which was defended by Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal. In 211, he defeated and killed the two Roman commanders Publius and Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio, near Castulo.

However, the Romans were able to reorganize their army, which was commanded by Publius Cornelius Scipio, the son of the man who had been defeated by Hasdrubal. In 209, Scipio captured Carthago Nova, the Carthaginian capital in Iberia, and Massinissa is recorded to have been active in this area in the following year. By this time, Hasdrubal was trying to bring reinforcements to his brother in Italy (in vain), and the Carthaginian army, under new leaders, was slowly forced back to Andalusia. In 206, they were decisively defeated near Ilipa, and Scipio proceeded to capture the last Carthaginian strongholds.

At this moment, Massinissa must have understood that Rome was to win the war. He negotiated with his opponents, and both parties agrees that if the Romans would invade Africa, Massinissa would help them. The Massylian prince had good reasons to conclude this deal, because in the meantime, his father had died, and the kingdom had been taken over by his brother Oezalces. The Romans could help Massinissa become king.

Unfortunately, Rome did not strike immediately. Scipio was first sent to Sicily, from where he first had to reconquer the “toe” of Italy to secure the Strait of Messina. Meanwhile, the two competing Massylian factions were easy victims for another enemy, king Syphax of the Masaeisylians. Massinissa was still able to assist a first Roman expedition to Africa, commanded by Scipio’s deputy Laelius -together they looted the camp of Syphax- but in the end, Massinissa lost his position, and when Scipio finally made his appearance in Africa in 203, the Numidian could offer only 200 cavalry.

Yet, now that the Romans were there, he was able to recover his ground. In the battle on the great plains, Syphax and the Carthaginian commander Hasdrubal, son of Gesco, were defeated, and while the Roman general concentrated on Carthage, Massinissa followed Syphax to Cirta, where he took him prisoner.

Among the captives was also Syphax’s wife Sophoniba (daughter of Hasdrubal), with whom Massinissa had once been engaged. He now married her, and when Scipio showed interest in this woman, who was a fierce Carthaginian patriot, Massinissa decided to poison her.

In the meantime, Hannibal had arrived on the scene, but on 19 October 202, Scipio defeated the Carthaginian general near Zama. Massinissa’s cavalry played an important role in this battle. Almost immediately, Carthage surrendered. Massinissa was rewarded with the throne of all Numidia. His reign was to last more than half a century.

In this period, he developed the country economically. Cities multiplied and continued to grow, trade benefited, agriculture was intensified. In 179, Numidia produced a surplus, and Massinissa could present himself as the benefactor of the Greek island of Delos, which gave him credentials in the Greek-Roman world as leader of a civilized nation. In the company of Scipio and his relatives, Massinissa also met the Greek historian Polybius of Megalopolis, who seems to have liked the Numidian king and describes him as a cultivated man, whose mission it was to civilize his country. The positive tone of our sources is essentially based on Polybius’ portrait.

As an ally of Rome living near its arch-enemy, Massinissa could always raid Carthaginian land, or simply claim that it was his. Rome would always help him (e.g., in 193, 182, 174, 172). So he gained ports in the north and east (e.g., Sabratha, Oea [in 162/161], and Lepcis Magna).

Coin of Massinissa, showing an unidentified man and a horse (©!!)

In 154, Carthage decided to strike back, and began to build an army. Immediately, the Romans, who learned from it from an envoy of Massinissa, investigated the case, and they tried to strike a compromise. But Massinissa’s raids continued, and in 151, the Carthaginians declared war upon the Numidians. The king, who was now ninety-two years old, defeated his enemies, who were commanded by Hasdrubal. Carthage now also incurred a war against the Romans. In 146, the city was sacked.

Massinissa died in 148, shortly after the Roman invasion. The Roman historian Livy records that he had been “so vigorous that among the other youthful exploits that he performed during his final years, he was still sexually active and begot a son when he was eighty-six” (Periochae, 50.6). He left his kingdom to his three sons Micipsa, Gulussa, and Mastanabal.

King Jugurtha, who was to be a famous enemy of Rome by the end of the second century, was a son of Mastanabal.

En Francais

In the third century BC Massinissa was king of the Numidians. His Father, Gaia, was king of the Massylies.

On the death of the father, the inheritance received allowed the son to achieve unity of the 2 tribes, the Masaesyles and the Massyles into a single people. Thus began the building of the western history of North Africa. In this northern region of the African continent, if the distant past of Egypt and Libya has been clearly established, the countries located to the west of Tripolitania is only known in a hypothetical manner before the advent of Carthage.

But then came Massinissa and North Africa enter the history of the world. And it may be because of this exceptional reputation that European and Arab writers, perhaps anxious to shine chapters relating to their own countries, have dodged the person and work of this prestigious character: the King of Numidia.

It seems that the name of Massinissa is a nickname rather ripe for a nickname. First, we must decompose the name in “Mass”, and “Inissa”. “Mass” means “Sir”, as “Massa” means “Lady”. Then it is likely that this king has been nicknamed “Inissi” word meaning Hedgehog, which has become “Inissa” by use or by distortion. Indeed this chief had a reputation for being picky and uncompromising, or “prickly” in its relations, just as he should have a tendency to withdraw into himself to literally become an impregnable ball when under adversity. That did not prevent him from being recognized of high value.

Upon his accession to the throne, now unified under his leadership, Massinissa began to realize a vast empire across this vast west Mediterranean area. That dream immediately bumped into a double hostility:

that of Carthage, who did not want to see its prestige eclipsed on the extent of the land of Africa and,

that of Rome, which opposed any competition of its force in the Mediterranean.

He should therefore strengthen itself to impose his mark on those two powerful neighbors, dominant to Africa and rival between them. The measures taken at the domestic level were:

1. settle mainly nomadic population to cultivate and develop the country’s wealth; 2. establish fixed markets fueled by economic circuits; 3. create and lead an army commander composed of infantry and cavalry used separate or combined; 4. innovate militarily using elephants as part of heavy fighting.

As expected from the outside, the rivalry between Rome and Carthage has degenerated into what was called the Punic wars. In this case, Carthage, mistress of Africa, had money but lacked experienced troops to support combat. It was therefore natural that Massinissa was asked to help Phoenicians washing the affront received at their defeat against the Roman army. The bargaining were accompanied by numerous offers from Carthage, in case of common victory, involving Moors and Numidians in the conduct of war operation. To various clauses regarding expenditure and rewards, it was included the granting of citizenship of Carthage with the advantages related to the benefit of combatants and their relatives.

The organizational Expeditionary Force reserved the supreme command of the convoy to the Phoenician Hannibal, who joined the convoy in transit and surrounded by a consequent commandment. The operational management of troops remain to the Numidian Massinissa, especially because of the African languages spoken by the fighters of the Expeditionary Force in Africa. The war was won. But the Carthaginian Senate disowned its commitments regarding the promised granting of citizenship. This alliance thus betrayed was therefore forced to break. Therefore, Carthage, reduced again to its own elements, was again defeated by the Romans, and this time destroyed.

The lessons learned from this adventure are fabulous:

1. prodigious entry of the battles Berber forces in the history of the universe; 2. revelation of a major Numidian warlord ; 3. creating of a great tool of war with:

organization and training of combat units on foot, and / or horseback;

introduction of elephants in the battle-group;

organizing and training of transportation’s units : on land, and sea;

organization and training of command levels ;

organization and training of media;

organization and training of stewards to man and animals;

coordination of food supply and resources of combat;

coordination of all elements in static position and / or movement;

coordination of combatants during the rough-and-tumble;

organization of groups, en route stops, or forehead;

separation of powers and areas in: tactics, strategy, logistics, command execution, and replacement, etc..

That is what the Carthaginians were wasted by losing their alliance with the Africans. That is also what the Romans discovered at Massinissa and they seek to recover for their armies.

Another famous Berber will reuse these values to his ascension, since he will provide the leadership of Rome: Septimius Severus.

In addition to the worth of this illustrious ancestor, worth being included in the gallery of heroes models of all time, it should be noted:

the rule of multi weapon command, multi army and intercontinental command, imposed by the technician es-profession of arms;

the now accepted dominant role of Africa in the western Mediterranean;

the invention of an emblem that would be perpetuated through space and time as the flag.

NUMIDIA DESPUES DE MASINISA

A la muerte de Masinisa en 148, Escipión el Africano dividió el reino entre sus hijos. En 113, Yugurta se alzó contra los romanos y acabó derrotado, tras lo cual Numidia fue gobernada por un rey vasallo de Roma hasta que, bajo Diocleciano, se convirtió en una simple provincia del imperio y finalmente volvió a manos de los bereberes hasta la invasión de los vándalos en 430.

A principios del siglo VI, las tropas de Justiniano I expulsaron a los vándalos y recuperaron el reino para el Imperio Bizantino, que lo gobernó de manera precaria hasta la llegada de los árabes en el siglo VIII.

Los romanos dejaron importantes ciudades en el norte de Argelia, entre las que destacan Iol Caesarea, Tipasa (Tipaza), donde se encuentra una de las necrópolis más antiguas conocidas en el Mediterráneo, Cuicul, Calama, Thubursicu-Numidarum (Khemissa), Madaure, Thamugadi (Timgad), Diana Veteranorum, Theveste (Tébéssa) y Lambaesis.

EL PUEBLO BEREBER

Berber people

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are discontinuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke various Berber languages, which together form a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Today many of them speak Arabic. Between 30 and 40 million Berber-speakers live within this region, most densely in Algeria and Morocco, becoming generally scarcer eastward through the rest of the Maghreb and beyond.

Many Berbers call themselves some variant of the word Imazighen (singular: Amazigh), possibly meaning “free people” (the word has probably an ancient parallel in the Roman name for some of the Berbers, “Mazices”). According to Leo Africanus, Amazigh meant “free men”, though this has been disputed because there is no root of M-Z-Gh meaning “free” in modern Berber. It also has a cognate in the Tuareg word amajegh, meaning “noble”).[5][6] This is common in Morocco, but elsewhere within the Berber homeland a local, more particular term, such as Kabyle or Chaoui, is more often used instead.[7] Historically Berbers have been variously known, for instance as Libyans by the ancient Greeks,[8] as Numidians and Mauri by the Romans, and as Moors by medieval and early modern Europeans. The modern English term is probably borrowed from Italian or Arabic, but the deeper etymology of “Berber” is not certain. (See also: Berber (Etymology).)

The best known of them were the Roman author Apuleius, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus, and Saint Augustine of Hippo.[9] A famous Berber living today is the international football star Zinedine Zidane.

[edit] Etymology

Because “Berber” appeared for the first time after the end of the Roman Empire, the relevance of its use for the previous period is not accepted by all historians of antiquity [10], and is still considered wrong.

The use of the term spread in the period following the arrival of the Vandals at the major invasions. Described as “barbarians” by the Romans in Roman Africa, and from the Iberian peninsula where their camps were subjected to repeated attacks of the Romans. On the hills to the east of Numidia was assembled coalition numido-vandal, who will remove Carthage and Rome’s influence throughout Africa. The story of the Roman consul in Africa fit reference for the 1st time the term “barbarian” to describe Numidia. Arab historians, some time after, will appoint the Berbers[11].

[edit] Prehistory

A Berber family crossing a ford - scene in Algeria

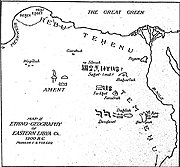

Medghasen tomb, one of the earliest tombs known

Tingis (Tangiers)

according to Berber mythology, the town was built by Sufax, son of Tinjis, the wife of the Berber hero Antaios.

Early inhabitants of the central Maghreb left behind significant remains including remnants of hominid occupation from ca. 200,000 B.C. found near Saïda. Neolithic civilization (marked by animal domestication and subsistence agriculture) developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghrib between 6000 and 2000 B.C. This type of economy, so richly depicted in the Tassili-n-Ajjer cave paintings in southeastern Algeria, predominated in the Maghreb until the classical period. The amalgam of peoples of North Africa coalesced eventually into a distinct native population. The Berbers lacked a written language and hence tended to be overlooked or marginalized in historical accounts.

The Berbers have lived in North Africa between western Egypt and the Atlantic Ocean for as far back as records of the area go. The earliest inhabitants of the region are found on the rock art across the Sahara. References to them also occur often in ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sources. Berber groups are first mentioned in writing by the ancient Egyptians during the Predynastic Period, and during the New Kingdom the Egyptians later fought against the Meshwesh and Libu tribes on their western borders. From about 945 BCE the Egyptians were ruled by Meshwesh immigrants who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty under Shoshenq I, beginning a long period of Berber rule in Egypt. They long remained the main population of the Western Desert—the Byzantine chroniclers often complained of the Mazikes (Amazigh) raiding outlying monasteries there.

For many centuries the Berbers inhabited the coast of North Africa from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean. Over time, the coastal regions of North Africa saw a long parade of invaders and colonists including Phoenicians (who founded Carthage), Greeks (mainly in Cyrene, Libya), Romans, Vandals and Alans, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans, and the French and Spanish. Most if not all of these invaders have left some imprint upon the modern Berbers as have slaves brought from throughout Europe (some estimates place the number of European slaves brought to North Africa during the Ottoman period as high as 1.25 million).[12] Interactions with neighboring Sudanic empires, sub-Saharan Africans, and nomads from East Africa also left impressions upon the Berber peoples.

In historical times, the Berbers expanded south into the Sahara (displacing earlier populations such as the Azer and Bafour), and have in turn been mainly culturally assimilated in much of North Africa by Arabs, particularly following the incursion of the Banu Hilal in the 11th century.

The areas of North Africa which retained the Berber language and traditions have, in general, been the highlands of Kabylie and Morocco, most of which in Roman and Ottoman times remained largely independent, and where the Phoenicians never penetrated far beyond the coast. But, these areas have been affected by some of the many invasions of North Africa, most recently including the French.

Some pre-Islamic Berbers were Christians[13] (but evolved their own Donatist doctrine),[14] some were Jewish, and some adhered to their traditional polytheist religion. There were three African popes of probable Berber ancestry who came from the Roman province of Africa.[citation needed] Pope Victor I served during the reign of Roman emperor Septimus Severus, of Roman/Berber ancestry, who had led Roman legions in Roman Britain and against the Arsacid Empire.[15]

[edit] History of Berber people in the Maghreb

Berber population in Egypt

During the pre-Roman era, several successive Independent States (Massylii) existed before the king Massinissa unified the people of Numidia.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches (Botr and Barnès), descended from their ancestor Mazigh, which were further divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (eg Sanhadja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, Berghwata, etc). All these tribes had independence and territorial decisions.[22][23]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb, Sudan, Andalusia, Italy, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Egypt, etc. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarizing the Maghreb dynasties: Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid , Meknassa, ,,… Hafsides dynasties.[24][25]

They belong to a powerful, formidable, brave and numerous people; a true people like so many others the world has seen - like the Arabs, the Persians, the Greeks and the Romans. The men who belong to this family of peoples have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.

—

Ibn Khaldun, 14th century Arab historian[14]

[edit] Numidia

Numidia (202 BC – 46 BC) was an ancient Berber kingdom in present-day Algeria and part of Tunisia (North Africa) that later alternated between being a Roman province and being a Roman client state, and is no longer in existence today. It was located on the eastern border of modern Algeria, bordered by the Roman province of Mauretania (in modern day Algeria and Morocco) to the west, the Roman province of Africa (modern day Tunisia) to the east, the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Sahara Desert to the south. Its people were the Numidians.

The name Numidia was first applied by Polybius and other historians during the third century BC to indicate the territory west of Carthage, including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 100 miles west of Oran. The Numidians were conceived of as two great tribal groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii under their king Gala were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli under king Syphax were allied with Rome. However in 206 BC, the new king of the eastern Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax of the Masaesyli switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa of the Massylii. At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa’s territory extended from Mauretania to the boundary of the Carthaginian territory, and also southeast as far as Cyrenaica, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage (Appian, Punica, 106) except towards the sea.

After the death of Masinissa he was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa’s illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, of Berber origin who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarrelled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.

After Jugurtha defeated him in open battle, Adherbal fled to Rome for help. The Roman officials, allegedly due to bribes but perhaps more likely because of a desire to quickly end conflict in a profitable client kingdom, settled the fight by dividing Numidia into two parts. Jugurtha was assigned the western half. (Later Roman propaganda claimed that this half was also richer, but in truth it was both less populated and developed.)