Statue head of Hathor, Serabit el-Khadim. The goddess, clearly indicated from her horned headdress,

is depicted with the visage of Nefertari, chief wife of the Nineteenth Dynasty ruler Ramesses II.

Quartzite: height 25 cm. Fitzwilliam Museum E.4.1905 (Antiquities).(Fitzwilliam E 4 1905(2)

-

-

Vista general del templo de Serabit el-Khadim

-

www.touregypt.net/featurestories/serabit.htm

- Bonnet, Charles, Le Saout, F. and Valbelle, Dominique [1994], “Le temple de la déesse Hathor, maîtresse de la turquoise, à Sérabit el-Khadim. Reprise de l’étude épigraphique”, CRIPEL 16 (1994), pp.15-29.

- Gardiner, Alan H. and Peet, T. Eric [1952], The Inscriptions of Sinai, London, 1952, pl.92 (plan).

- Gundlach, R., “Serabit el-Chadim”, LdÄ V, 866-868.

- Mumford, Gregory [2006], “Egypt’s New Kingdom Levantine Empire and Serabit El-Khadim, Including a Newly Attested Votive Offering of Horemheb”, JSSEA 33 (2006), pp.159-203.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders, Researches in Sinai (with chapters by C.T. Currelly), London: J. Murray, 1906, pp.72-108, pls.85-113.

- Starr, R.F.S. and Butin, R.F. [1936], “Excavations and Protosinaitic Inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadim”, Studies and Documents VI, London, 1936.

- Valbelle, Dominique [1996], “Chapelle de Geb et temple de millions d’années dans le sanctuaire d’Hathor, maîtresse de la turquoise”, Genava, NS 44 (1996), pp.61-70.

- Valbelle, Dominique and Bonnet, Charles [1996], Le sanctuaire d’Hathor, maîtresse de la turquoise: Sérabit el-Khadim au Moyen Empire, Paris: Picard, 1996. ISBN 2708405144

- [1997], “The Middle Kingdom Temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim”, in Quirke, Stephen (ed.), The Temple in Ancient Egypt—New Discoveries and Recent Research, London: British Museum Press, 1997, pp.82-89. ISBN 0714109932

- -

-

Templo de Hathor,Serabit el-Khadim.Sinaí

-http://static.panoramio.com/photos/original/8430033.jpg

LAS TURQUESAS

La Turquesa es un fosfato de aluminio y cobre. Tiene brillo de cera a mate.Su origen es secundario en las partes superficiales de rocas con un elevado contenido en P y Cu,como en la zona de oxidación de algunos yacimientos de Cu. Existen cristales pequeños cerca de algunos yacimientos de Cu. Existen cristales pequeños cerca de maden(Irán).Otras localidades son Cortez,Nevada,Los Cerrillos,y Eureka(Nuevo Mexíco). Se conocen concreciones verde azuladas y azules masivas en Monte Ali Mirsai,cerca de Maden(Irán).

Otras localidades son Cortez,Nevada,Los Cerrillos y Eureka(Nuevo México), y Bisbee,Arizona(E.E.UU.).Se asocia a limonita,calcedonia.

Irán,durante al menos 2000 años,la region antes llamada Persia, se ha mantenido como la fuente principal de abastecimiento de Turquesas.

Estas turquesas,de “color perfecto”,sólo se encuentran en una mina ubicada en la cima de la montaña Ali-Mersai de 2.012 metros,a 25 km de Mashad,la capital de la provincia de Korashan.

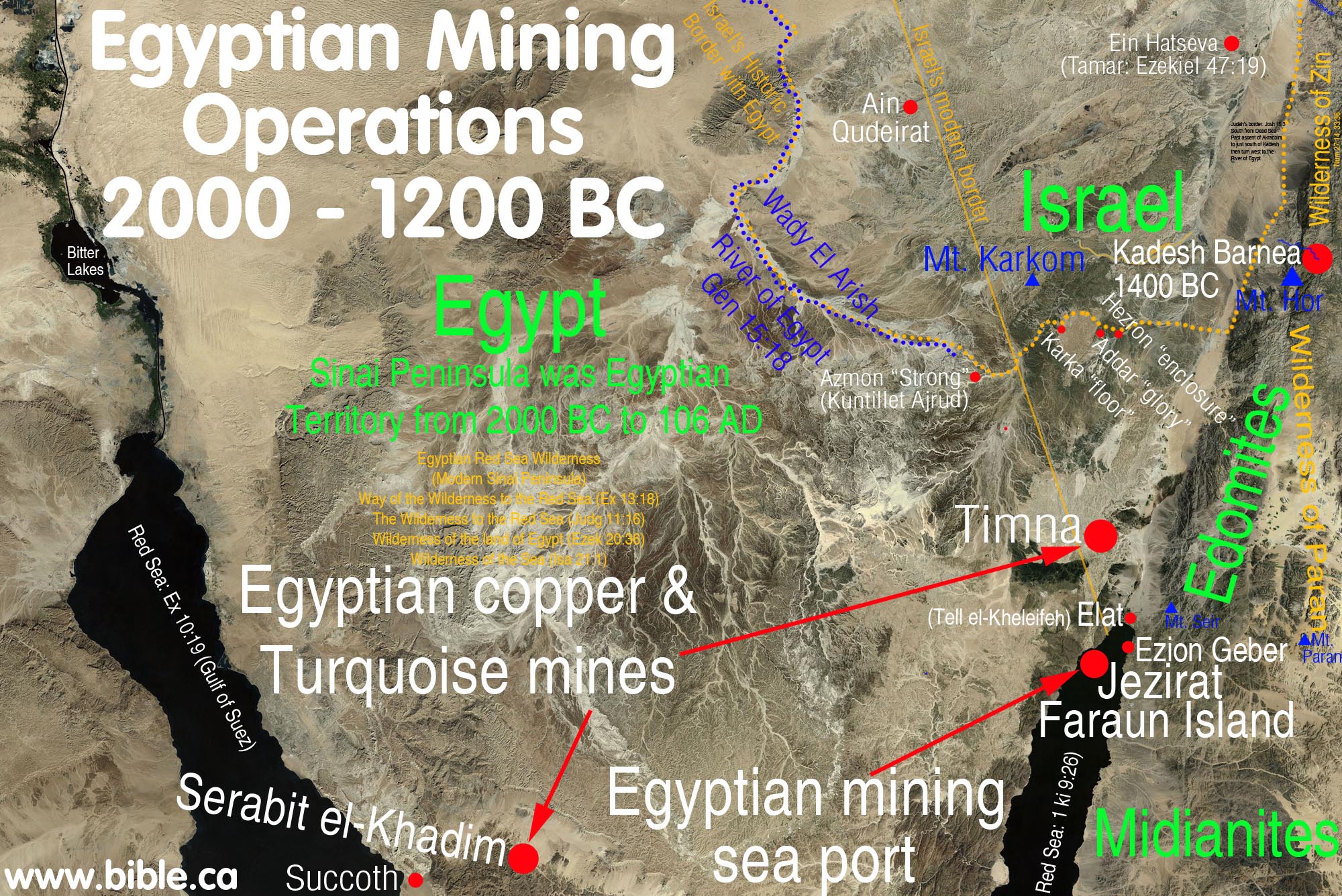

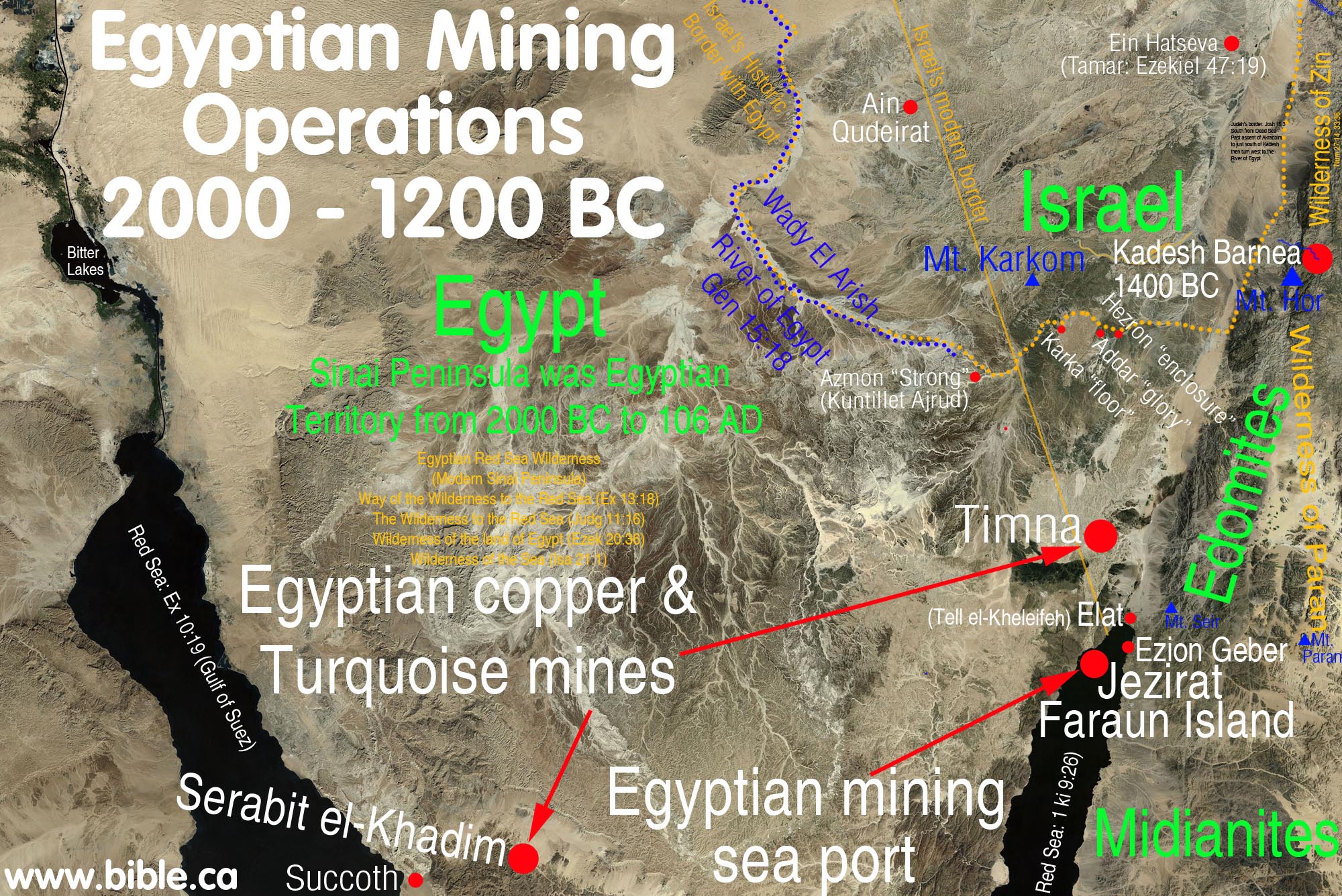

En la península egipcia del Sinaí,desde al menos la I dinastia(año 3000 a.C),las turquesas fueron utilizadas por los antiguos egipcios,que las extraían de la peninsula de Sinaí,llamada ¨Pais de Turquesas¨ por los nativos.

Hay 6 minas en la región,todas situadas en la costa sudoeste de la peninsula.

Las dos minas más importantes,desde un punto de vista histórico,estan en Serabit el-Khadim y Uadi Maghara,y se encuentran entre los yacimientos conocidos más antiguos.

_jpg/350px-Serabit_el-Khadim_(reconstruction).jpg)

Serabit-el-khadim

Artist’s reconstruction of the sanctuary at Serabit el-Khadim in the late New Kingdom period. After Sydney Aufrere L’Égypte Restituée: Sites et temples des déserts, 1994.

La mina esta localizada a unos cuatro kilometros de un antiguo templo dedicado a la diosa Hathor(divinidad cósmica,diosa del amor,de la alegría,la danza y las artes músicales,diosa nutricia y patrona de los ebrios en la mitologia egipcia).

En el sudoeste de los Estados Unidos se encuentran yacimientos significativos de turquesas:Arizona,California,Colorado,Nuevo México y Arizona,todos ellos son o eran especialmente ricos en este mineral.China ha sido un yacimiento de menor importancia hace 3000 años o más.Gemas de calidad en forma de nodulos compactos son encontradas en Yunxian y Zhushan,en la provincia de Hubei.Ademas Marco Polo relato haber encontrado turquesas en Shinchuan.

Minerales semejantes son la crisocola,más blando; azurita azul más intenso; variscita,claramente verde.

| Title |

Author |

Date |

Publisher |

|

| Complete Temples of Ancient

Egypt,The |

Wilkinson, Richard H. |

2000 |

Thames and Hudson, Ltd |

|

| Dictionary of Ancient Egypt,

The |

Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul |

1995 |

Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers |

|

| History of Ancient Egypt, A |

Grimal, Nicolas |

1988 |

Blackwell |

|

| Oxford History of Ancient

Egypt, The |

Shaw, Ian |

2000 |

Oxford University Press |

|

-

————————————————————————————————————————

-

Sinai’s turquoise goddess

A comprehensive restoration and documentation scheme is underway at a major temple and mine complex in Sinai, as

Nevine El-Aref reports

From pre-dynastic times, early Egyptians made their way to the Sinai Peninsula over land or across the

Red Sea in search of minerals. Their chief targets were turquoise and copper, which they mined and extracted in the Sinai mountains.

Archaeologists examining evidence left 8,000 years ago have concluded that some of the very earliest known settlers in Sinai were miners. In about 3,500 BC these mineral hunters discovered the great turquoise veins of Serabit Al-Khadim. Some 500 years later the Egyptians had mastered Sinai and set up a large and systematic mining operation at Serabit Al-Khadim, where they carved out great quantities of turquoise. They carried their loads down the Wadi Matalla to the garrison port at Al-Markha, south of the present village of Abu Zenima, where they set about loading them on board boats bound for the mainland.

The turquoise was so valued that it became an important part of ritual symbolism in ancient Egyptian religious ceremonies. They used it to carve sacred scarabs and fabricate jewellery, or ground it into pigments for painting statuettes, bricks, reliefs and walls.

To mine the turquoise, the Egyptians would hollow out large galleries in the mountains, carving at the

entrance to each a representation of the reigning Pharaoh who was the symbol of the authority of the Egyptian state over the mines.

A temple dedicated to Goddess Hathor was built during the 12th Dynasty, when Serabit Al-Khadim was the centre of copper and turquoise mining and a flourishing trade was established. One of few Pharaonic monuments known in Sinai, the temple is unlike other temples of the period in that it is composed of a large number of bas-reliefs and carved stelae showing the dates of various turquoise-mining missions in antiquity, the number of team members, and the goal and duration of each mission. From dynasty to dynasty, the temple was expanded and beautified, with the last known enlargement taking place in the 20th Dynasty.

To reach the temple the visitor must pass through a sequence of 14 perfectly-cut blocks that form ante-rooms, and even a small pylon, before reaching the central courtyard. At the far end of this courtyard are the sanctum and two grottos, where the gods Hathor and Sopdu were adored and where their images still remain. This part of the temple was accessible only to the priests and the Pharaoh. Regretfully, a colonial British attempt to reopen the mines in the mid-19th century led to some of the reliefs being destroyed.

The site of Serabit Al-Khadim, which lies on top of a mountain 2,600 feet above sea level, was discovered by British archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1905. Petrie unearthed several royal and private sculptures, stelae and sacrificial tools dating back to the time of the Fourth-Dynasty King Senefru.

Petrie also found vestiges of the Proto- Sinaitic script, believed to be an early precursor of our modern alphabet. These scripts began with hieroglyphic signs used to write the names of the people who worked in the mines and to keep account of their labours. The signs developed into an “Aleph-Beta” script that recorded a Proto-Canaanite language. The script that developed, Proto-Sinaitic, was used to write a Pan-Canaanite language.

The Serabit Al-Khadim temple resembles a double series of stelae leading to an underground chapel dedicated to the goddess Hathor. Many of the temple’s large number of sanctuaries and shrines were dedicated to Hathor who, among her many other attributes, was the patron goddess of copper and turquoise miners. As we have seen, the earliest part of the main rock-cut Hathor Temple, which has a front court and portico, dates from the 12th Dynasty and was probably founded by Pharaoh Amenemhet III, during a period of time when the mines were particularly active.

A number of scenes depict the role of Hathor in the transformation of the new Pharaoh, into the deified ruler of Egypt, which took place on his ascension to the throne. One scene depicts Hathor suckling the Pharaoh. Another scene from a stone tablet depicts Hathor offering the Pharaoh the ankh symbol, or key of life.

This older part of the temple was enlarged upon and extended during the New Kingdom by none other than Queen Hatshepsut, along with Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep III. This was a regeneration period for mining operations after an apparent decline in the area during the Second Intermediate Period. These extensions are unusual for a temple in the manner in which they are angled, that is to the west of the earlier structure.

On the north side of the temple is a shrine dedicated to the Pharaohs who were deified in this region. On one wall of the shrine are numerous stelae. A little to the south of the main temple is a shrine dedicated to Sopdu, god of the Eastern Desert, which is smaller than the northern shrine.

Today, the whole site is being subjected to restoration and documentation in order to make it more accessible to visitors and more tourist-friendly. Mohamed Abdel-Maqsoud, head of the central administration for Lower Egypt antiquities, said that the restoration, which will take about a year on a budget of LE500,000, would remove all the signs of time that marred the temple’s walls and reliefs. It would also consolidate them and strengthen the fabric and colours of the wall paintings. The restoration will be carried out by a mission from the SCA, while the documentation will be implemented in collaboration with CULTNAT which will provide the necessary technical assistance and equipment.

Zahi Hawass, secretary-general of the SCA, said that every relief would be photographed, drawn and videotaped on its four sides and then returned to its original position. A site management project would also be implemented.

Abdel-Maqsoud promises that by 2010 a proposal will be presented to the World Heritage Organisation for the Serabit Al-Khadim archaeological site to be included on the World Heritage List.

-

-

_jpg/350px-Serabit_el-Khadim_(reconstruction).jpg)