Arqueólogos de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén han descubierto en el norte de Israel la tumba de una mujer chamán, que incluye los caparazones de 50 galápagos, la pelvis de un leopardo y un pie humano de 12.000 años de antigüedad. Les Natoufiens existaient dans la région Méditerranéenne du Levant, il y a plus de 15 000 ans.

Cette découverte est précieuse, car le chamanisme est la première de toutes les religions, souvent pratiquée par des femmes qui avaient une connaissance de la nature, des animaux et des plantes étonnantes.

El hallazgo, que corresponde al período Neolítico, se cree que es uno de los más primitivos que se conocen del enterramiento de un chamán en toda la región, según refiere un comunicado difundido hoy por la universidad jerosolimitana.

Leore Grosman, del Instituto de Arqueología del centro académico y que dirige la excavación en Hilazon Tachtit, en la Galilea occidental, cree que los preparativos y el ritual empleados para el enterramiento, así como el método para sellar la tumba, sugieren que la sepultada tenía un papel destacado en la comunidad. Y sugiere que esta tumba podría señalar cambios ideológicos que tuvieron lugar en aquel entonces debido a la transición hacia la agricultura en la región.

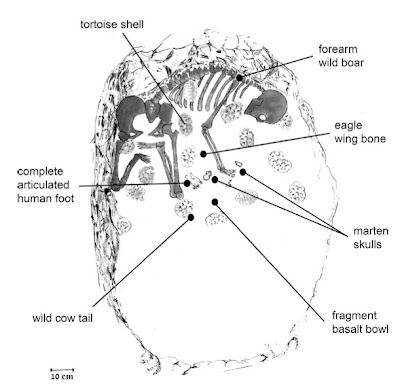

Dibujo de la tumba de la chamana hallada en Israel

CONTENIDO DE LA TUMBA.AJUAR.

PROTEGIDA POR UN ÁGUILA DORADA

La tumba contenía restos de varios animales, raramente encontrados en enterramientos del período Neolítico, como cincuenta caparazones completos de tortugas, la pelvis de un leopardo, la punta del ala de un águila dorada, la cola de una vaca, los esqueletos de dos hurones, y el antebrazo de un jabalí salvaje, que apareció alineado con el húmero izquierdo de la mujer.

APARIENCIA Y EDAD DE LA MUJER y OTROS RESTOS HUMANOS

Asimismo, fue descubierto un pie humano de un individuo considerablemente más alto que la sepultada, que era de pequeña estatura y tenía 45 años en el momento de fallecer, según análisis de sus huesos.

La chamán también tenía una apariencia asimétrica debido a una incapacidad vertebral que podría haber afectado su modo de andar, lo que pudo causarle cojera.

TEORÍA DE GROSMAN

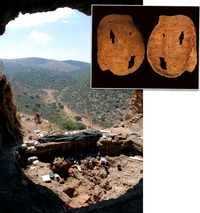

Death and dinner. Archaeologists claim that a great feast, including the consumption of 71 tortoises (inset), accompanied the burial of a woman at Israel’s Hilazon Tachtit cave.

Grosman considera que :

.1. Sepultura especial que refleja su status.

El enterramiento responde a lo que los expertos asocian con las tumbas de chamanes, pues generalmente los enterramientos reflejan el papel que desempeñaba el individuo, y suelen aparecer junto a los animales y otros objetos con los que se relacionaron en vida.

2.Método especial

El método de enterramiento también es peculiar:

-La mujer reposaba de lado, con su columna, pelvis y fémur derecho contra la pared curva de la tumba, que es de forma ovalada y sus piernas aparecieron separadas y dobladas hacia dentro a la altura de las rodillas.

-PIEDRAS

El arqueólogo menciona que sobre la cabeza, la pelvis y los brazos de la mujer fueron colocadas diez piedras en el momento de su sepultura, y que tras la descomposición del cuerpo, su peso provocó la desarticulación de algunas partes del esqueleto, como la separación de la pelvis de la columna vertebral.

Se cree que una de las razones de esta práctica fue evitar que la fallecida fuera comida por animales, o porque la comunidad trató de salvaguardar su espíritu dentro del ataúd.

-Restos del posible banquete funerario

También se presume que los cuerpos de las tortugas pudieron haber sido comidos como parte del funeral, ya que muchos de los huesos indican que la mayor parte fueron arrojados a la tumba junto a los caparazones tras su consumo.

“Claramente se ha invertido una gran cantidad de tiempo y energía para la preparación, arreglo y sellado de la tumba”, manifestó Grosman, quien agrega que el cuerpo también recibió un tratamiento especial antes de recibir sepultura.

El período Neolítico existió en la región del Creciente Fértil entre 15.000 y 11.500 años, y el arqueólogo explica que el descubrimiento podrá arrojar luz sobre los cambios ideológicos que se produjeron durante este período de transición a la agricultura e información sobre lo que se puede considerar “la primera religión de nuestra civilización”.

Las excavaciones se llevaron a cabo en una pequeña cueva donde han sido desenterrados los cuerpos de al menos 28 individuos de distintas edades del período Neolítico.

(See “Oldest Shaman Grave Found; Includes Foot, Animal Parts.”)

A study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Grosman and Natalie Munro, a zooarchaeologist at the University of Connecticut, reveals that the shaman’s burial feast was just one chapter in the intense ritual life of the Natufians, the first known people on Earth to give up nomadic living and settle in villages.

In the years that followed the burial, many people repeatedly climbed the steep, 492-foot-high (150-meter-high) escarpment to the cave, carrying up other members of the community for burial as well as hauling large amounts of food. Next to the graves, the living dined lavishly on the meat of aurochs, the wild ancestors of cattle, during feasts conducted perhaps to memorialize the dead.

New evidence from Hilazon Tachtit, in northern Israel’s Galilee region, suggests that mortuary feasting began at least 12,000 years ago, near the end of the Paleolithic era. These events set the stage for later and much more elaborate ceremonies to commemorate the dead among Neolithic farming communities.

In Britain, for example, Neolithic farmers slaughtered succulent young pigs 5,100 years ago at the site of Durrington Walls, near Stonehenge, for an annual midwinter feast. As part of the celebrations, participants are thought to have cast the ashes of compatriots who had died during the previous year into the nearby River Avon.

(See “Stonehenge Was Cemetery First and Foremost, Study Says.”)

The Natufian findings give us our first clear look at the shadowy beginnings of such feasts, said Ofer Bar-Yosef, an archaeologist at Harvard University.

“The Natufians,” Bar-Yosef said, “were like the founding fathers, and in this sense Hilazon Tachtit gives us some of the other roots of Neolithic society.”

Study co-author Grosman agrees. “The Natufians,” she said, “had one leg in the Paleolithic and one leg in the Neolithic.”

Prehistoric Feast Focused on Disabled Shaman

Perched high above the Hilazon River in western Galilee, Hilazon Tachtit cave was long known only to local goatherds and their families. But in the early 1990s Harvard’s Bar-Yosef spotted several Natufian flint artifacts scattered along the arid, shrubby slope below the cave and climbed up to investigate.

Impressed by the site’s potential, the Harvard University archaeologist recruited Hebrew University’s Grosman to take charge of the dig, and she and a small team began excavations there in 1995.

First Grosman and her team had to peel back an upper layer of goat dung, ash, and pottery sherds that had accumulated over the past 1,700 years. Below this layer they found five ancient pits filled with bones, distinctive Natufian stone tools, and pieces of charcoal that dated the pits to between 12,400 and 12,000 years ago.

At the bottom of one pit lay the 45-year-old shaman—quite elderly for Natufian times—buried with at least 70 tortoise shells [NM2] and parts of several rare animals.

Analyses showed that this woman had suffered from a deformed pelvis. She would have had a strikingly asymmetrical appearance and likely limped, dragging her foot.

Grosman examined historical accounts of shamans worldwide and found that in many cultures shamans often possessed physical handicaps or had suffered from some form of trauma.

According to Brian Hayden, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, “It’s not uncommon that people with disabilities, either mental or physical, are thought to have unusual supernatural powers.”

Source From Great Site : http://news.nationalgeographic.com

The evidence that these remains represent a real feast and not just ritual placement of animal parts into the burial is considerable, the authors contend. The wild cattle bones come from all parts of the skeleton (including the head, the neck, all limbs, and the feet), and the bones show clear signs of cut marks, indicating that the animals were butchered. The tortoise shells were broken in such a way to make the meat easily accessible, and some of them showed signs of burning, suggesting that they were roasted. Moreover, underscoring the woman’s apparent special status, her head was placed on top of one tortoise shell, and the other shells were arrayed above, below, and around her body. The researchers estimate that the total yield of cattle and tortoise meat, at least 17 kilograms, could have fed 35 or more people.

Brian Hayden, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, says that the new evidence is “very convincing” and represents the “best documented case” of early feasting to date. Hayden, who has argued that feasting was key to the social transition between hunter-gatherer and farming societies, suggests that the revelers at Tachtit Hilazon might have been part of a secret shamanistic society.

Ian Kuijt, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, agrees that the team has carried out “excellent research.” But he argues that Munro and Grosman have not fully proved that this was an actual feast rather than the remains of a communal meal without much symbolic significance. “Do all communal meals serve as feasts? No,” Kuijt says, adding that the size and scale of the event are not reliable indicators of feasting. He says that a large neighborhood barbecue might not commemorate anything in particular, whereas a small Thanksgiving dinner might have great symbolic meaning.

Archivado en: ACTUALIDAD, ARTÍCULOS, Arqueologia, Costumbres, Curiosidades, General, H. Próximo Oriente

Trackback Uri