The achievements of antiquity are being re-attributed so that all of humanity can claim it as a joint accomplishment. Somehow, and not by coincidence, it is the Greeks who are being written out of this history.

Here is a brief consideration of two claims:

PURPLE

Murex, la concha de la que se obtiene la púrpura

1/ It is claimed that at c. 1200 BC, the Phoenicians invented “Tyrian purple”, a dye made from the murex sea-snail.

www.daimonas.com/…/editing-greeks-history.html

However, archaeological findings in Krete (Crete) at Komos has unearthed murex shells which show that the Minoans cultivated the sea-snail in factory farms for the production of the purple dye at least 300 years before it appeared in Tyre ( this was popularised by Bettany Hughes’ recent documentary series shown in October 2004 in the UK & May 2005 in Australia

http://search.abc.net.au/search/cache.cgi?collection=abconline&doc=http/www.abc.net.au/tv/guide/netw/200505/programs/ZY7203A001D8052005T193000.htm)

Indeed even in Homer’s Odyssey (put into writing in the early 8th century BC, reciting events from 5 centuries earlier) the importance of the colour purple to the Mycenaean royalty is made repeatedly showing that the royal purple predates 1200 BC. (The latest entry in the wikipedia now dates the production of “Tyrian purple” to 1700 BC and attributes it to Krete).

ALPHABET

2/ Around 1600 BC, the Phoenicians invent the first purely phonetic alphabet. The Greeks it is argued had nothing to do with the creation of the alphabet other than to add vowels to it. However this too is a gross simplification.

THE GREEK BASIS OF THE “PHOENICIAN” ALPHABET

The Phoenicians never developed an alphabet. Their achievement was a consonantal script , not an alphabet, which was written in cuneiform: reed imprints.

The assumption that the Greeks learnt the alphabet from the Phoenicians is based on Herodotus who made that claim in his Histories. What Herodotus did not know was that his ancestors were literate. Nearly one thousand years before his birth Achaean Greeks were writing in the script we know as Linear B. Indeed, the history of Mycenaean civilization, its subsequent collapse and the colonies these Mycenaeans set up in Kyprus (Cyprus) and along the Levantine coast to Gaza, is instrumental in understanding how the “Phoenicians” came to adopt Greek-Mycenaean symbols to write with; and then adopted Greek/Mycenaean shipping to trade along the same sea-routes that had been established by the Minoans & then Mycenaeans before them. (And as to what the ships used by the Minoans and Mycenaeans looked like, we can learn from the wall-paintings at Thera which date to before c. 1623 BC).

There is some inkling of the Mycenaean basis of what came to be the phenomenon of “Phoenician” civilization.

“During the 14th and 13th centuries Aegean Mycenaeans were arriving on the island [Kyprus (Cyprus)], at first as merchants, but towards the end of this period as settlers also, and they were also settling in some numbers… not only in north syria at Ugarit… but in Phoenicia proper and further south as well… Thus some of the interconnections between Phoenicia and Cyprus from the 13th century onwards may have been due more to the existence of Mycenaeans in both than of Phoenicians.” p. 52 The Phoenicians by Donald Harden. And, “Cypro-Poenician connections were strong… the so-called Cypro-Phoenician pottery of the 9th century and later is really descended from Mycenaean wares…” p. 53 (Harden)

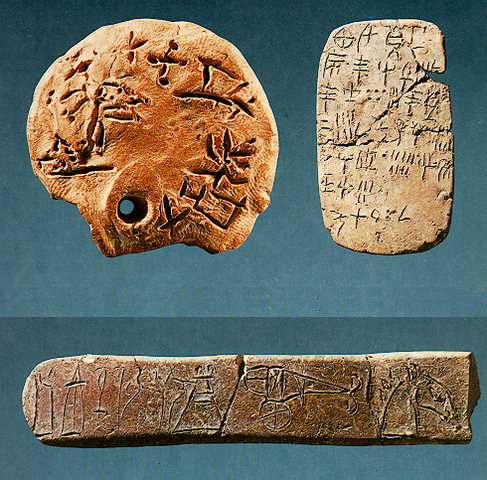

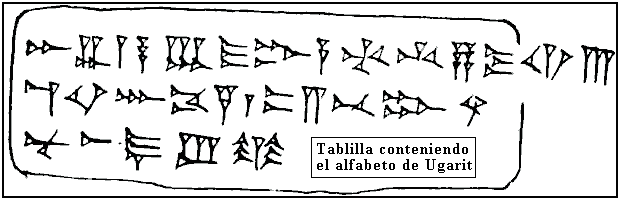

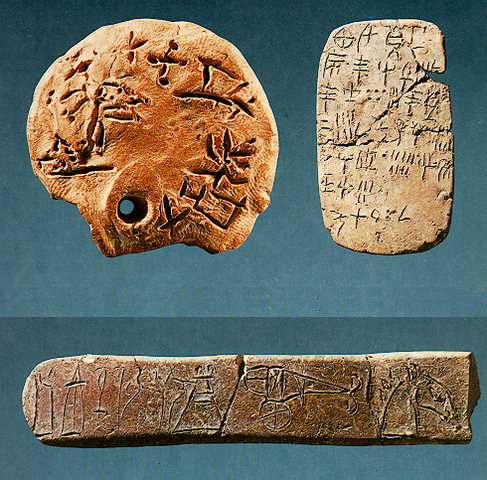

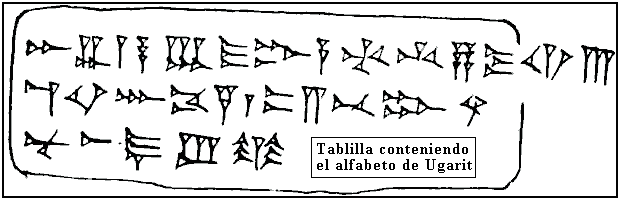

Tablilla de Ugarit con 28 signos

In Ugarit , the Semites there were already using a pseudo-alphabetic script written in cuneiform, not the script of symbols we are familiar with as “the alphabet”. However, this was no true alphabet, for one group of sounds was not represented: vowels. This is a consonantal script, not an alphabet.

The deciphering of Linear B by Michael Ventris in 1953 was accomplished because the Cypriot Script was already understood & known to be Greek.

It is of interest that the Phoenicians set up posts in the 9th century BC in Kyprus (Cyprus), & that the Semites of the Syrian coast already had a consonantal script written in cuneiform ( Ugarit tablets). Cyprus already had Mycenaean colonists in the west of that island from the 12th century BC which predate the Phoenician settlements which are founded during the 9th century BC.

The development of the alphabet and the introduction of a script of symbols to replace the cuneiform is not explained in current assessments. It is only when it is realised that this script was derived from the Minoan/Mycenaean Linears A and B (respectively), that an explanation becomes possible.

Tablilla con signos en Lineal A minoicos

And it is this script which was introduced to the Levant from the west which occurs only after the Mycenaeans settled in the Levant en masse after the collapse of Bronze Age civilizations. To understand how the alphabet proper which accommodates all sounds (and not simply consonants) could have developed, has to take into account all historical information, and not limit itself to propounding what has become orthodox ideologically-driven dogma. The Greek Linear B was a syllabic system which combined a consonant with a vowel.

The pre-”Phoenician” (as they later came to be called by Greeks) Canaanites themselves had a history of adopting different writing systems and throwing out as ballast sounds other than consonants.

These pre-Phoenician “Canaanites” already used, in this way, Egyptian logograms and cuneiform to express consonants. Therefore the adoption of another system, this time one from Mycenae, could be seen to be consistent with their history. However, the “Phoenicians” simply took up incised symbols replacing their reed-imprint symbols; that is they adopted and adapted for their use the syllabic symbols of the Linear A/B/Cypriot Scripts & used those symbols to represent their own consonantal script. On this basis it would appear that the Greeks then took back their own Minoan/Mycenaean script which had been modified by Phoenicians and modified it again by re-introducing vowels. The only problem that remains here is the question of why abandon the cuneiform when it obviously worked? It has to be remembered that cuneiform was never replaced in the hinterland for another 700 years after the “Phoenicians” adopted an incised script - so it is not as if it was any more difficult to express ideas using reed-imprints. This could be answered in the context of the changing traditions in writing materials and technology. The increasing use of papyrus would have made it increasingly cumbersome to draw small triangles when a series of lines would be a far simpler and clearer task. Even when using clay, it is much simpler to incise lines than to make multiple imprints into a pattern which is the basis of cuneiform. But it is only when it is taken into consideration that the “Sea-People” Philistines were Mycenaean, as evidenced at settlements such as those at Ekron, that any explanation of why those who wrote their Semitic language in cuneiform adopted the Greek “grapsas” can be explained: In Ekron the Mycenaean Philistines had, by 900BC, abandoned their own language and adopted the Semitic language of the people they had settled among. Mycenaean-Greek scribes adapted the Semitic language to their grapsas style of writing. Yet the Philistines, despite being Semiticised, always maintained some contact with their homealnd, as has been shown at Ekron, and this Mycenaean adaptation of their grapsas script to the Semitic was reapplied by these Semiticised Mycenaeans of the Levantine coast, the so-called “Phoenicians”, to the language they originally spoke: Greek. The evidence actually points to Mycenaean scribes adapting the same (similar) sets of symbols to represent both languages. The evidence actually shows that the Greek alphabet and the Phoenician alphabet have the same common point of origin in the lands in which settled the already literate Sea-People. The so-called “phoenician” alphabet using incised symbols arose at the same time as did the Greek.

| The Jewish Old Testament refers to both Phoenicians, and Philistines as being Kretans: Jeremiah 47.1-4“This is the word of the LORD that came to Jeremiah the prophet concerning the Philistines before Pharaoh attacked Gaza…the day has come to destroy all the Philistines and to cut off all survivors who could help Tyre and Sidon. The LORD is about to destroy the Philistines, the remnant from the coasts of Caphtor [Krete].”The Septuagint version of the same passage reads: Jeremias 24.1-4 “Behold, waters come up from the north… in the day that is coming to destroy all the Philistines: and I will destroy Tyre and Sidon… for the Lord will destroy the remaining inhabitants of the islands.”The Philistines and Phoenicians were considered to be the same people whose origins lay in the islands and were not native to the Levantine coast. |

Donald Harden writes The Phoenicians :

“From Mycenaean times there must have also have been some Aegean element in Phoenician religion, but it was not till much late, in the second half of the first millennium BC, that classical Greek influences began to predominate. From then on cult objects, figurines architecture and even coffins are made in the Greek spirit and - no doubt -mainly made by Greek artists. This happens in Carthage, too, from the fourth century onwards, and is an earnest of how all-pervading Greek influence was and how impossible it proved for any nation to withstand its onslaught.” p. 76

What is evident is that the Semites of the Levantine coast came under successive waves of Hellenic influence from the time of the Achaean Greeks of Mycenae to the Greeks of the Hellenistic period.

The antiquity of European writing

The tablets from Tartaria, Rumania with inscriptions. They are from the 6th millennium BC, thus predating writing in mesopotamia by 2000 years.This is the writing system to which “Old European” has been ascribed. It includes the scripts/inscriptions of Neolithic Greece.Reference source:

The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe : Myths and Cult Images

By: Marija Gimbutas isbn: 0520046552 |

Inscribed spindle-whorl from Neolithic Greece. Inscriptions in the form of “pot marks” continued in Greece (particularly at Lerna) until the period of the creation of Linear A in the 17th/16th century BC in Krete.

Reference source:

The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe : Myths and Cult Images

By: Marija Gimbutas isbn: 0520046552 |

An example of Linear B script. This was translated by Michael Ventris and shown to be Greek. Linear B has been dated to no earlier than 1375 BC. It replaced the Linear A of Krete, and shared many of the symbols and associated sound values. |

The antiquity of European writingThe following comes from the Chapter “The signs of Old Europe: Writing or Pre-Writing?” from Richard Rudgley’s book Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age.“…the signs of the Tartaria tablets were also similar to those found in the Minoan scripts of Crete although they were clearly not Cretan. The string holes , whilst absent in Mesopotamia, were a common feature of Cretan tablets…” (p.61). The speculation regarding the tablets was that if they were writing then their origin had to lie in transmission from the Near East, on the supposition/assertion that “The barbaric priests of Europe [merely] sought to imitate their cultural ‘superiors’ from the east by superstitiously seizing upon writing for magical purposes..” (p.61) without really understanding it.Yet, even if the “Vinca signs” did not quite represent writing, “The Vinca signs thus represent a sophisticated system of communication… a system of pre-writng.” (p.66) The problem for scholars however has been the age of this “script” and what that implies:“…scholars on realising that the Vinca signs were simply too early to be derived from Mesopotamia, abruptly dropped the question of the European script. Without the comfort of leaning on Near Eastern origins, few of them dared to pursue the question of an independent emergence of writing in Europe.” (p.68)Rudgley comments on the absurdity of the situation. As long as the Tartaria symbols were considered newer than Sumerian writing, they were unquestioningly accepted as writing. Once they were found to predate Sumerian writing, “the tablets were dismissed as meaningless jumbles of signs.” p.68 !The appearance of Linear A in Krete too corresponds to the revised dating of Kretan civilization and appears to be in use after c. 1600 BC with the arrival of new peoples to the island. (Professor N. Platon has developed a chronology to replace that of Arthur Evans based on the palaces’ destruction and reconstruction. He divided Minoan Krete into Prepalatial (2600-1900 BC), Protopalatial (1900-1700 BC), Neopalatial (1700-1400 BC), and Postpalatial (1400-1150 BC). The palaces of the Protopalatial period were destroyed in c. 1700 BC by either an earthquake, or invaders. It seems a little too coincidental that a new script appeared on the island shortly after this and that the earlier Kretan hieroglyphic script (Phaestos disc) is replaced.Bulgaria is the most likely source of this influx and accounts for the similarities of the Linear A, with the “Old European” Vinca symbols which are known to have had a long history there. That Linear A has been found there shows that there were links between Bulgaria and Krete. Additionally the model of appropriating symbols that served different purposes to the people that had used them supplies us with the model of how a new modified model would come about. |

The two images above show the similarity between the symbols on the Tartaria Tablets with those of the Minoan Linear A (Left). The image on the right shows Linear A compared to Linear B found on the Greek mainland and in Krete with the Cypriot-Greek Script and gives the respective sound-values.According to H. Haarmann, as quoted in Rudgley’s book Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age “It would be a misconception to say that the Cretan Linear A is a derivation from the Old European script. However, almost one third of the sign inventory of the Old European script [above left] has been revived in the Linear A sign list where these elements make up almost half the total inventory.” p. 70

Both Linears A and B were preceded by what are referred to as “pot marks” (illustrated below) which were used by potters in neolithic Greece (e.g., Lerna) and in the Aegean islands.

Illustration of Greek potmarks which precede both Linears A and B.

The illustration is from Greece in the Bronze Age by

Emily Vermeule

Mycenaeans transported their wares across the Mediterranean, from Sardinia to Egypt. Below is illustrated a Mycenaean stirrup jar which features Linear B writing on it. This example was excavated in Thebes and was imported from Krete. Archaeological evidence shows that Thebes had extensive trade contact with the Near East. Cuneiform tablets have been unearthed in Thebes. However, Mycenaean scribes never took up the Near Eastern form of writing preferring their own. Conversely, niether did those with whom the Tebans traded in the Near East take up the Greek writing - at least not until after the collapse of the Myceanaean world and the “Sea People” settled in the Near East following the Mycenaean’s collapse. The Greek word for writing “grafos” (familiar to Anglophones in examples such as photograph) comes from the word “grapsas”, to scratch, as used by Homer in the Iliad. According to the way in which history is told, the Greeks, though in contact with the Near East and familiar with the Near East writing style of reed-imprints (cuneiform) preferred instead to scratch symbols. In accordance to this historical scheme, writing was a Near Estern invention which radiated from its Near Eastern source. However, the Greek “grapsas” not only has an independant evolution from the Near East, but eventually came to replace the various forms of writing like cuneiform that had been employed for writing in the Near East for at least a millennium. |

There is a concerted push to attribute to the Near East all manner of history. However, the reality contradicts such an attribution, despite how passionately the desire for this to be so might be. The motivation to so attribute civilization to the Near East is not guided by scholarship, but by a desire not to “Eurocentricise” history as it is assumed was done in the Third Reich. There are authors like ML West, a translator of classical Greek writing, who attributes most of the Greek achievement to the Near East.

The means by which West et al achieve this, is by the deliberate omission of pre-Classical Greek artefacts, like the snake goddess and her votary found at Knossos (on display in the Museum of Herakleion) . These predate Hesiod’s mention of Hecate by nearly a millennium. Thus when, in Apollonius’ Argonautica, appears the night wandering snake festooned Hecate Brimo the convenience of omission explains her as an “appearance” due to “Near East influence”. Though the Kretan snake-goddess is the best known snake motif in pre-classical civilization on Greek soil, she is not an isolated instance. She is also depicted on Mycenaean gems (illustrated below) dating to c.1500 BC, and coiled clay snakes have been found in Mycenae. “Hecate Brimo”, rather than being an appropriation by Hesiod (in c. 700 BC) from the Near East (specifically Anatolia), was already part of the Greek pantheon.

Illustration from p.43 Art of Crete, Mycenae, and Greece by

German Hafner

The snake goddess, adorned with horns, appears in Late Neolithic Krete showing the pedigree of the snake goddess on Krete as well as her extreme antiquity (note her feet which taper into “snake-tails”):

Image source:

The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe : Myths and Cult Images

By: Marija Gimbutas isbn: 0520046552

Rather than a Near East component, the truth is closer to Greek soil. Elements in Hesiod which have come to be attributed to the Near East by authors such as West is the conflation and reconciliation of separate indigenous traditions with very old pedigree coexisting within Greece which has nothing to do with the Near East.

Claims that aspects of Greek mythology, such as Typhon, who it has come to be claimed came from a foreign (non-Greek) source, can only be made if it is not realised what role “myths” played in pre-literate societies. Mythology is not mere fanciful folk-telling, but the technical scheme by which events are told with the intention that they be remembered. In the example of Typhon, he is the volcanic eruption at Thera which occurred in 1623. This was a force from the core of earth (Gaia) who challenged and fought the gods of heaven. This momentous event was seen as a challenge of the god who reigned in the overworld by the gods of the underwolrd. That Hurrian and Hittite tales appear to tell a similar tale, though with differing motifs, is because all these cultures witnessed the same event and recounted it according to their understanding of what forces were at play, and in the context of the cosmology they believed in. Indeed, the tale travelled from west to east, and not vice-versa, becoming, on reaching India, the clash of Indra with Vritra.

The influences that are evident in Greece actually emanate from the north and west, (and the Aegean islands) especially when seen in the context of the association of Linear A in Bulgaria and Krete (remembering that no Linear A has ever been found on the Greek mainland) and that the Vinca culture, like that of Krete, worshipped the snake-goddess (after Haarmann p.68 Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age) .

History is being written contrary to the evidence available and is guided by motives that are outside the bounds of historical pursuit: the desire to be inclusive of the sensitivities of others, in some instances; whilst in others it is attempting to demonstrate the validity of the “wisdom” of the Bible by attributing civilization to the Near East to ‘prove’ the delusion that the bible is an historical document, ‘the word of god’, and that it is thus the basis for all human ‘wisdom’. Such pursuits are not genuine history, and are simply the perpetration of a cultural fraud. The achievement of the Greeks can best be understood as the achievement of a hybridised people, an ‘indigenous’ development that only arose when the non-Indo-European “Old European” peoples of the Greek mainland, the Aegean islands and Krete became absorbed with the invading Indo-European Greeks. The Greek world rather than being the western rump of Near Eastern civilization was instead independent of it. Phoenician civilization instead was the eastern rump of a western civilization; they were Hellenised (Mycenaeanised) Semites who absorbed Mycenaean colonists (refer recent archaeological evidence from Ekron), who for a while became the sole challengers to the Greeks. Their greatest city Carthage came to rival Alexandria - until the Romans sacked it so completely that we can never properly reconstruct it.

Maybe by 2010-2012 I will have finished my research and written my book. This essay serves only as an introduction to a thesis.

Additional references:

[ An online reference to the development of Cypriot writing:

http://www.allenwood.org/essays/cypruswriting.html ]

[ Linear B and Related Scripts by John Chadwick ]

[ The Mycenaeans (Ancient Peoples and Places) by William Taylour ]

[ The Use and Appreciation of Mycenaean Pottery in the Levant, Cyprus and Italy (ca. 1600-1200 BC)

(University of Chicago Press link) by Gert Jan van Wijngaarden ]

[ Greek Writing from Knossos to Homer: A Linguistic Interpretation of the Origin of the Greek Alphabet and the Continuity of Ancient Greek Literacy

by Roger D. Woodard

Quoting from the Amazon Editorial Review:

"'In this book, Woodard examines the origin of the Greek alphabet. Deviating from previous accounts, he places the advent of the alphabet at a point within an unbroken continuum of Greek literacy beginning in the Mycenean era. Woodard argues that the creators of the Greek alphabet, or, more accurately the adapters of the Phoenician consonantal script, were scribes accustomed to writing Greek with the syllabic script of Cyprus. Certain characteristic features of Cypriot script, gestures which arose from the idiosyncratic Cypriot strategy for representing consonant sequence and from the intersection of this strategy with elements of Cypriot Greek phonology, were transferred to the new alphabetic script. Proposing this Cypriot origin to the alphabet at the hands of previously literate adapters clears up various problems of the alphabet, such as the Greek use of the Phoenician sibilant letters. The alphabet, though rejected by the post-Bronze Age "Mycenaen" culture of Cyprus, was exported west to the Aegean, where it gained a foothold among a then illiterate Greek people emerging from the Dark Age." ]

![[image]](../../online/reviews/aphrodite/thumbnails/goddess.gif)

![[image]](../../online/reviews/aphrodite/thumbnails/hittite.gif)

![[image]](../../online/reviews/aphrodite/thumbnails/egyptian.gif)

![[image]](../../online/reviews/aphrodite/thumbnails/aegean.gif)

![[image]](../../online/reviews/aphrodite/thumbnails/priestess.gif)