Akkadian cuneiform Origin

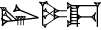

lú.shab.tur shumallû `pupil’

The Akkadian cuneiform script was adapted from Sumerian cuneiform in about 2350 BC. At the same time, many Sumerian words were borrowed into Akkadian, and Sumerian logograms were given both Sumerian and Akkadian readings.

61 MU

- phonetic: mu

- phonetic:, new: ia5

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: mu

- logograms: MU MU

umu `name’ MU zakäru `to speak’ MU zikru `name’ MU

umu `name’ MU zakäru `to speak’ MU zikru `name’ MU  attu `year’, `harvest time’ MU.AN.NA

attu `year’, `harvest time’ MU.AN.NA  attu `year’, `harvest time’

attu `year’, `harvest time’

In many ways the process of adapting the Sumerian script to the Akkadian language resembles the way the Chinese script was adapted to write Japanese. Akkadian, like Japanese, was polysyllabic and used a range of inflections while Sumerian, like Chinese, had few or no inflections.

The Akkadian script was used until about the 1st century AD and was adapted to write many other languages of Mesopotamia, including Babylonian and Assyrian.

Notable features

* Between 200 and 400 symbols were used to Akkadian, though in some texts many more appear.

* The symbols consisted of phonograms, representing spoken syllables, determinatives, which indicated the category a word belonged to and logograms, which represented whole words.

* Many of the symbols had multiple pronunciations.

Used to write:

Akkadian, a Semitic language that was spoken in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq and Syria) between about 2800 BC and 500 AD.

Sample text

Links Free Akkadian fonts (TeX and LaTeX only)

http://space.tin.it/clubnet/bxpoma/akkadeng/cf_fonts.htm

The Akkadian language pages - details of the Akkadian language and writing system: http://www.sron.nl/~jheise/akkadian

http://www.sron.nl/~jheise/akkadian

Other cuneiform scripts Akkadian, Elamite,-Elamite,-

Old Persian Cuneiform,-Old Persian Cuneiform—

Ugaritic-Ugaritic-

http://images.google.es/imgres?imgurl=http://www.geocities.com/stonerdon/Genesis/GcsumermapB.gif&imgrefurl=http://www.geocities.com/stonerdon/Genesis/ContextGenesis.html&usg=__9xiKNIstFVuLLuEIFnJhizqNalI=&h=271&w=326&sz=19&hl=es&start=54&um=1&tbnid=baA5bFTz_iH_HM:&tbnh=98&tbnw=118&prev=/images%3Fq%3DLarak%2Bsumerian%2Bcity%26ndsp%3D20%26hl%3Des%26lr%3D%26rlz%3D1G1GGLQ_ESES297%26sa%3DN%26start%3D40%26um%3D1

Chapter 4 of John Heise’s ‘Akkadian language’ on the origin and development of cuneiform.

[

Back to main Index]

Quick to the chapters [

Intro] [

Mesopotamia] [

Texts] [

Language] [

Books] [

Links]

4. Cuneiform writing system

Table of contents

- Origin

- 3-dimensional clay tokens

- pictograms

- Clay tablets

- Physical appearance of cuneiform signs

- Order of cuneiform signs in sign lists

- value of cuneiform signs

- phonogram (homophony, polyphony)

- logogram

- phonetic complement

- determinative

- Cuneiform Signs Lists

- cuneiform fonts for use in TeX and LaTeX

Writing is one of the essentials and characteristics of civilization. Urbanization, capital formation and writing are closely related. Writing developed at the end of the 4th millennium in the Middle East. The prime motivation was of an economic nature: the desire to administer economical and trade transactions. Almost all of the early cuneiform texts and a very large fraction of the 2nd millenium texts concern economy and administration.

A comprehensive theory concerning the origin of writing was developed by Denise Schmandt-Besserat, University of Texas.

1.1 Three dimensional clay tokens

Already from the 9th millennium onwards clay tokens (Lat. calculi) where used to depict objects and abstract numbers and was widely spread: from present day Sudan to Iran. The clay tokens in various forms and shapes were used as counters. Each type of counter represent e.g. a bull’s head, a sheep, a basket, a bar of gold etc. They were, in many cases at least, pictographicallly used: that is, they depicted concrete objects. They have meaning in any language. Further specification was obtained with diacritical marks, such as scratches and strokes. It was the first steps towards an abstract notation.

In the second half of the 4th millennium clay bullae developed. (see a later example in this external image, or this external description): envelopes of clay used to contain the tokens. The bullae were used in transactions, as trafel documents, waybill, contract of carriage etc. To certify the content cylinder seals where used (see example in this external image, or this external description) that were roled over the wet clay.

It seems that a further step was to imprint the tokens on the outside of the clay bulla. The content could thus easily be identified. It was the first step in the development of a writing system. Numbers were given as simple strokes: one stroke for ‘one’, two strokes for ‘two’ etc. Note that the same is true for our currentthe symbols for the number 1, 2 and 3. The writing of the number 2 is merely two horizontal strokes, in cursive writing written with ‘pen down’ in between. Our symbol for the number 3 developed from three horizontal strokes on top of each other in cursive writing.

Larger units are obtained as an impression of the round rear side of a reed stylus.

Hold vertically the impression would be

A skew impression would give

Still larger units could be a combination

The actual meaning of these number symbols may depend on the units measured: one, six, ten, sixty, ten times sixty etc. In the famous stratification layer Ur-IVa (around 3200 BC) in the ancient city of Ur also symbols that represent the unit 100 are found. The symbols were collected in sections. The order of the signs within a compartment was not important.

A diacritical mark on a three dimensional token was often not clearly copied on the outside of a clay bulla and had to be inscribed by hand. In the two dimensional writing a symbol like could stand for ‘sheep’, not a pictogram anymore. Further diacritical marks, like removing a segment could indicate ‘ewe’ (female sheep) where as removing two segments could be an indication of a sheep in gestation.

1.2 Pictograms

At the end of the 4th millennium an explosion of new signs suddenly appeared, most of which have no counterpart as 3-dimensional token, of which there are only a dozen or so. (This, by the way, is also seen as sever criticism of the development from 3-dimensional tokens sketched above). This development took place simultaneously with the building of the first cities, large palaces and temples etc. In general with an economy that was more centralized and where the emphasis was shifted gradually from concentration of villages to larger units.

The writing system was born, basically as pictograms. The signs were curvilinear in shape. Symbols that never appear in a 3-dimensional form are:

A hand, that showed like

A head looked like

A foot was

The pubic triangle of a women as and stands for ‘woman’ or ‘female’ in general.

The word ‘day’ was symbolized as the sun at the horizon

Since the drawing of curvilinear lines in clay is cumbersome, lines are imprinted (stamped) with a reed stylus and curvilinear shapes gradually make place for straight lines, and the shapes simplified. Specific meaning was obtained with further diacritical marks, such as

and so cuneiform (In English and French, from Lat. cuneus ‘wedge shaped’, German ‘Keilschrift’) was born. In the Akkadian writing more than a millennium later one can still recognize (knowing the intermediate steps) the pictographic origin of the signs. The Akkadian logogram (word sign) for ‘woman’,'female’ is the sign munus developed from a straight line approximation and rotation over 90 degree from the pubic triangle

The logogram for ‘mountain’ kur was an actual drawing of a mountain peak. Mountains, however, are not present in Mesopotamia, which is in the alluvial plains around the rivers Eufraat and Tigris. The word ‘mountains’ (north of Mesopotamia) therefore also symbolizes ‘abroad’, ‘foreign country’. The Sumerian word (and later the Akkadian logogram) for ‘female slave’ is represented by the composite logogram, in Akkadian:

munus.kur a combination of ‘woman’ and ‘foreign/mountain’, thus the word for ‘female slave’ is ‘woman from the mountains/from abroad’

(Note that the English word ‘slave’ has a similar origin: Slavic people where brought in large numbers as slaves to western Europe in the 10th century, during an intense period of ”Christianization”)

Pictografic writing would have meaning in any language, but the development is usually ascribed to the Sumerians. The Sumerian language has no proven relation with any other language.

Some of the earliest tablets can be seen on the Web, see Catalogue.

(to be written)

Cuneiform (from Latin meaning ‘wedge-shaped’) is composed of a series of short straight wedge-shaped strokes made with a stylus into a tablet of soft clay. The strokes are thickest at the top, like , on harder material it more looks like . At first, symbols were written from top to bottom; later, they were turned onto their sides and written from left to right. In later periods harder materials were also used.

Five basic orientations are applied: horizontal, two diagonals, a hook and a vertical stroke:

The up-diagonal stroke has limited use. These five components occur in two different sizes. A small hook often not being distinguishable from a short diagonal. The two diagonal strokes are not used as an individual sign, but the other types are. Reverse orientations (e.g. with the head of the wedge at the bottom) are hardly attested. The inverse vertical is rare on old tablets (sometimes the vertical in the sign for ‘hand’, which normally is . Already from the Old Babylonian period onwards this orientation is not seen anymore. A stroke from right to left does not occur at all, a characteristic on the basis of which one may recognize simple falsifications.

The signs underwent a significant evolution in the course of time (e.g. Old Babylonian in the 18th century BC, versus New Babylonian almost a millennium later), slightly different in the various dialects. Present day sign lists are sorted to New Assyrian shapes. The field of study is called Assyriology and originated in the previous century with the discovery of the Assyrian Library in Nineve. New Assyrian shapes are more quadratic. They void diagonal and hook shaped components as compared with the contemporary Babylonian scripts. E.g. the sign ni is in Assyrian form  and in Babylonian form .

and in Babylonian form .

Students usually start learning cuneiform signs in New Assyrian orthography. For the grammar Old Babylonian is studied as a starting point. For educational purposes I have included an Old Babylonian text (the Codex Hammurabi) in New Assyrian transliteration, combining Old Babylonian grammar with easier-to-learn signs.

[ Back to main Index] [Back to cuneiform Index]

The present day order of cuneiform signs such as used in sign lists is based on the following (arbitrary) sequence:

Also within the sequence starting with a horizontal stroke, this order applies to the remaining strokes. Within the signs starting with the sign precedes  etc.

etc.

The different orthography of some of the signs makes this sequence not completely unique.

[ Back to main Index] [Back to cuneiform Index]

The function of cuneiform divide in four basic ways, summerized here and described in somewhat more detail below

- phonogram,

representing a speech sound combination like ka, ak, kak, also called syllabogram when representing an entire syllable. [see 5.1]

- logogram,

representing an entire word or concept, also called Ideogram. In Akkadian logograms are often named Sumerograms, because they originate from Sumerian or quasi-Sumerian (=following the pattern of Sumerian). [see 5.2]

- phonetic complement, to select the choice of logograms and indicate grammatical form. [see 5.3]

- determinative

indicating a semantic content of a preceding or following word (either a logogram or a sequence of phonograms), e.g. when this word is to be considered the name of a deity, a man, a city, a thing made of wood, etc. They are not pronounced. Sometimes both preceding and following determinative are used. [see 5.4]

[ Back to main Index] [Back to cuneiform Index]

A phonogram is a signs that stands for a syllable, in general a two or three letter combination. It is said that the sign has phonetic value. With C a consonant and V a vowel, most signs have either CV or VC phonetic value, but (especially later in New Babylonian) CVC values occur more frequently. Akkadian phonograms are usually transcribed in italics, to distinguish it from logograms (capital or small capital).

The phonetic values are listed in the sign lists. Some of the signs have identical values throughout the Mesopotamian history and all of the dialects. Others are limited to the first half of the second milllenium, designated as “old” in the sign list, and mainly in use in the Old Babylonian Period. Sign values in use after this period are designated as “new” in the lists. An indication of geographical differences in the use of the signs are in these lists restricted to Assyrian (Ass.) and Babylonian (Bab.).

Homophony, different signs for the same value. The same sound combination may be represented by different signs. This is called homophony (from Greek

homos ‘same’,

phonè ‘sound’).

In transliterations the same sounds that are represented by different cuneiform signs are distinguished with an accent or an index. The signs for

ni, ní (i with accent-egu),

nì (i with accent-grave), ni

4, ni

5, …

are all different cuneiform symbols.

ní may be called (and pronounced among Assyriologists)

ni2 and

nì as

ni3.

These accents thus have nothing to do with word accent. Example:

ni

ní

nì

ni4

ni5

Since the use of accents is cumbersome in the htm-language of this document (and because accents are difficult to read at some servers) I will often use ni2 for ní etc. and ni3 for nì

Polyphony, same sign for different values. The same sign may stand for different syllables, all given in the sign lists. This is called

polyphony (from Greek ,i>polus, ‘many’,

phonè ‘sound’).

ni, né,lí,lé,ì,zal

and in later times also scal, dik, diq,tíq (sc for tsadeh, emphatic s, also written here with capital S: Sal)

The signs may be used within the same word for both values, e.g.

ì-lí = ili, the genitive of ilu ‘god’, or ilï (long i, not indicated in the writing) genitive plural ‘(of the) gods’

The choice of phonetic values for a sequence of cuneiform symbols is made such that a sensible word comes out. Surprisingly, the choice is in most cases unique and rarely one is left with some ambiguity. Polyphony makes the reading of cuneiform difficult for the layman.

Polyphony and homophony of cuneiform signs exists already since the early times (3000 BC), since the pictographic origin.

[

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index]

A logogram is the function of a sign as a concept, usually represented by an entire word. In Akkadian logograms are also called Sumerogram because most logograms have their origin in the Sumerian language, either taken from the Sumerian or as quasi-Sumerian: formed according to the rules of the Sumerian language (like Latin was used for new ‘Latin-like’ words in the church long after native Latin speakers existed).

The value of a logogram is usually transliterated in capital or small capital, using the Sumerian value, e.g. the sign used as a logogram for ilum ‘god’ is transliterated as DINGIR or dingir where dingir is the Sumerian word for ‘god’.

Grammatical forms of a word (e.g. the case for a nomen or the conjugation for a verb) are not expressed in a logogram. A logogram could stand for a nomen or adjective, but the same logogram could also be used as a verb, e.g. in the present tense or the past conjugation.

[

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index]

A logogram may be complemented with a phonogram, called phonetic complement. It is the last phonetic value of the word for which the logogram stands. It can be used to determine which particular choice of the logogrammatic value is meant, and often it helps in the interpretation of the grammatical function.

An English example would be the logogram X that could stand for either ‘cross’ or ‘Christ’. To facilitate reading and indicate what is meant the logogram is written with a phonetic complement -ing or -mas:

X-ing stands for ‘crossing’, e.g. in Ped X-ing ‘pedestrian crossing’

X-mas is logogram X + phonetic complement -mas for ‘Christmas’

Akkadian example: É + phonetic complement

= É, has logographic value bïtum ‘house’ (derived from Sumerian é meaning ‘house’)

= É, has logographic value bïtum ‘house’ (derived from Sumerian é meaning ‘house’)

The sign is developed from a pictogram showing a house. The ending -um (later -u) is the nominative (e.g. used when ‘house’ is subject in a phrase. The genitive (‘of the house’) is used to indicate that the word belongs to a noun (it modifies a noun). In Akkadian the genitive is also always used after prepositions. The genitive would be bïtim, with ending -i(m). One could write

É-tim = bïtim

É-tim = bïtim

that is the logogram É with phonetic complement -tim to indicate that the genitive is meant.

Akkadian example: AN + phonetic complement

The sign AN as logogram could mean the god Anum and amû ‘sky’, ‘heaven’. But with phonetic complement ú

AN-ú

AN-ú

it would mean amû ‘sky’, ‘heaven’.

[

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index]

A determinative (also called classifier) is the use of a sign to indicate to what class the following or preceding word belongs. This word could be either a logogram or a syllabically written word.

Example 1.

The sign AN is also used as a determinative to signal that the following word is a deity (or a demon). In that function the sign is in transcriptions abbreviated as d for Sumerian dingir ‘god’ (or an abbreviation of Latin deus ‘god’), written in raised position:

d UTU, the sun god Shamash, Sumerian utu (where utu here is used as an Akkadian logogram)

The god Anum which logographically is also written as AN, and is not preceded by a determinative.

Example 2.

My signature under these htm-documents

lú.shab.tur shumallû ‘pupil’

uses lu2 as a determinative for ‘man’ followed by e.g. the name of a profession. lu2 is also a logogram for awïlum ‘man’, ‘(male) person’. ab.tur is a logogram. Some clay tablets contain the name of the scribe followed by this logogram, indicating that the texts was copied by a student.

See e.g. list of determinatives for other examples.

A noun in plural could be represented by a reduplication of the logogram:

dingir.dingir = ilü (ü is long u) ‘the gods’

or as one of the logograms, e.g.:

dingir.dingir.gal = ilü rabütu ‘the great gods’, or:

dingir.gal.gal = ilü rabütu ‘the great gods’

A special type of determinative are the signs to indicate plural use of a logogram, mainly the sign ME

dingir.mesh = ilü ‘the gods’

[

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index]

6. Lists of cuneiform signs

- cuneiform sign lists as Web-pages

- cuneiform fonts for use in word processors TeX and LaTeX

[

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index] Quick to the chapters [

Intro] [

Mesopotamia] [

Texts] [

Language] [

Books] [

Links

]

As part of a colophon the ancient scribe could write the following (first 3 logograms and than phonetic values; bi is a Sumerian suffix, in Akkadian -shu, the pronoun ‘his’):

gim sumun.bi shà-thir-ma u ba-rì

‘as its original written and inspected’

by: j.heise @ sron . ruu . nl,

lú.shab.tur shumallû ‘pupil’

first installation on jan 6, 1995

last modification on May 4, 1995

With this top-20 one could read 50% of the signs in the Codex Hammurabi (whereas 40 signs would be good for 75% of the text, the remaining 25% is scattered over a large number of less frequently used signs). The total number of cuneiform signs is of order 600. The frequency of the use of the signs depends very much on the epoch and type of the text.

The sign list contains at least three items:

-a number from Borger’s book; Babylonisch-assyrische Zeichenliste’

-the cuneiform sign in New Assyrian orthography

-the name of the sign or one of its values.

Top-20 sign list

signs sorted by decreasing frequency of occurence in the Codex Hamurabi

70 NA

- phonetic: na

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: na

- e.g. used in the preposition a-na `for’, `to’, and

the preposition i-na `in’

- logogram: NA = awïlu (ï here for long i) `man’, `senior’ (NA mainly in use in omina)

579 A

- phonetic: a

the vowels a, e, i and u each have their own sign, which occur frequenly

- logogram: A = mu `water’.

In Sumerian A is `water’.

It developed (before rotation over 90 degree) from a pictogram showing waves.

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: a a

353

A (Sha)

- phonetic:

a (sha)

a (sha)

- a is also the possesive pronomen 3 fem.singular `her’; it is used as a suffix e.g.

a is also the possesive pronomen 3 fem.singular `her’; it is used as a suffix e.g.

shar- a `her king’

a `her king’

bël- a `her lord’

a `her lord’

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

a

a

354

U

- phonetic:

u (shu)

u (shu)

- u is also the possesive pronomen 3 masc.singular. `his’, hence its frequent occurence; it is used as a suffix e.g.

u is also the possesive pronomen 3 masc.singular. `his’, hence its frequent occurence; it is used as a suffix e.g.

ar-

ar- u `his king’

u `his king’

bël- u `his lord’

u `his lord’

- logogram:

U = qätu `hand’

U = qätu `hand’

It developed from a pictogram showing a hand.

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: and

343 GAL

- logogram: GAL = rabû `great’

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: GAL

461 KI

- phonetic: ki, ke, qí

- logogram: KI = erSetu `earth’ (S for sade, emphatic s)

- logogram: KI = a

ru `place’ (or ashru sh for shin)

ru `place’ (or ashru sh for shin)

- logogram: KI = kï preposition `as’, `like’ (ï for long i)

- determinative: after city names

61 MU

- phonetic: mu

- logogram: MU

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

342 MA

- phonetic: ma

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

214

BI

- phonetic: bi

- logogram: BI

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

13 AN, DINGIR

- phonetic: an

- logogram: AN = Anum the god of heaven, Sumerian AN

- logogram: AN =

amû `heaven’, Sumerian AN

amû `heaven’, Sumerian AN

- determinative: before gods and demons, in transcriptions abbreviated as d for Sumerian dingir `god’ e.g.

dUTU, the sungod  ama

ama , Sumerian utu

, Sumerian utu

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: DINGIR.ME

(ME

(ME is plurial sign) ilü ‘(the) gods’

is plurial sign) ilü ‘(the) gods’

DINGIR.ME (ME

(ME is plurial sign) ilü ‘(the) gods’

is plurial sign) ilü ‘(the) gods’

143 KÁM

142 I

Sumerian

i means `five’, the sign shows 5 strokes.

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

399 IM

- phonetic: im

- logogram: IM

318

Ú

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: and

449

I

- phonetic:

i,

i,  e20, igi, lim

e20, igi, lim

( i only in UTU-

i only in UTU- , =

, =  am

am i)

i)

- phonetic, new: lì, pàn

- logograms: IGI, LIM

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: IGI

69

BAD

- phonetic: be, bad/t/T

- phonetic, new: pát/T, bít, pít, mid/t/T, til, zis, ziz, sun, Ass.: qìt

- logograms: BAD, IDIM, SUN, SUMUN

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: bad bad

86 RI

- phonetic: ri, re

- phonetic, new: dal, tal, Tal, tala

- logograms:

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: tal

232

IR

- phonetic: ir, er

- logograms:

328 RA

- phonetic: ra

- logograms: RA

- examples in New Assyrian orthography: ra ra

381 UD, U

4

logogram: U

4 = UD =

ummu `day’

logogram: UTU =

ama

ama

the sungod, written with the determinative for deities as:

logogram: BABBAR = peSu `white’

= É.BABBAR Ebabbar

= É.BABBAR Ebabbar

`the White House’, famous temples of the sungod Shamash.

examples in New Assyrian orthography:

It developed (before rotation over 90 degrees) from a pictogram and showing sunset, hence the meaning `day’, `white’, `radiant’.

94 DIM

- phonetic: dim, tim, Tim

- phonetic, new: tì

- logograms:

231

NI

- phonetic: ni, né, lí, lé, ì, zal

- phonetic, new: Sal, dik/q, tíq

- logograms: Ì

- examples in New Assyrian orthography:

[

Next list] [

sign list index] [

Back to main Index] [

Back to cuneiform Index]

John Heise

Last change: Nov 14 1996

lú.shab.tur shumallû `pupil’

Maintained and updated by: j.heise @ sron . ruu . nl,

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

written in TeX or LaTeX with the use of cuneiform fonts, and obtainable in postscript file format.

-

e-nu-ma e-li

e-nu-ma e-li

Babylonian epic of creation, Enuma elish, tablet I

- cuneiform text + transliteration

(in .ps-file format, 8 pages)

with cuneiform on uneven pages and transliteration to syllables and words on even pages.

Or cuneiform text only in .gif-file format, in sets of separate images:

And transliteration in .gif-file format, in sets of separate images:

- About the epic of creation (to be written)

- First few lines explained in detail

- For translation see Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia

- a translation of all tablets is given elsewhere on the net [dead link?]

- Codex Hammurabi

[

Back to Main Index]

Quick to the chapters [

Intro] [

Mesopotamia] [

Cuneiform] [

Language] [

Books] [

Links]

Enuma elish, the Babylonian creation epos

The Babylonian Epic of Creation Enuma elish is written on seven tablets, each between 115 and 170 lines long. It was to be recited at the New Year festival in Babylon and reports about the success of the hero-god Marduk, the city-god of Babylon: how Marduk became the supreme deity, king over all gods of heaven and earth.

About the literary style

The epos is written in a style which is different from every day speach at the time. It uses an extended word variation with literary words that are normally not very frequent. This is characteristic for poetry. In prose texts there is no such inclination to use alternative formulations, like in the bible in Genesis I: ”And God saw …, and God saw …, and God created …, and God created ….” with little variation.

The text is constructed from two-line verses (sentence units). A concept is explained in two lines, a distich (from Greek di ‘two’ and stichos ‘verse’). The two members maintain a relation that one could call ”rhyme in an abstract sense” on the level of meaning. The meaning content of each verse appears in two parallel formulations often separated by leaving a blanc space, the so called parallelismus membrorum. The second part either emphasize the first part in different wording thereby extending the meaning, or the second part is an opposite statement, contrasting the first part. Compare the opening verse:

When above: the heaven has not been named

Nor earth below: pronounced by name

Metre in the strict sense in which Greek and Latin literature is composed (groups of long and short syllables) was not used, but a line often has three to four (rarely five) stresses/beats. End rhyme nor alliteration occurs.

The first primaeval beings: Tiamat and Apsu and their offspring

In the epic of creation Tiamat is the first primaeval being, primaeval Chaos, a kind of primordeal godlike creature that existed before the gods were created. These beings were thought of as being monstrous and having cosmic dimensions. In Akkadian tiamat means ‘sea’ and is used for the Perzian Golf (‘Nether sea’) and the Mediterranean Sea (‘Upper sea’), ‘nether’ and ‘upper’ with respect to the course of the rivers Euphrates and Tigre.

Tiamat is the (female) personification of ‘Sea’ and ‘sea water’. She appears as such in other epics as well. Names like Tiamat and the other primaeval beings to be mentioned (Apsu, Mummu) are missing the determinative sign for divinity . The reason is unknown but should not be seen in relation to their wicked disposition, because e.g. names of demons do carry this determinative sign.

Apsu, the second primaeval being that existed before the creation of heaven and earth, is the male personification of subterranean waters. The personification of Apsu (as somebody who acts and speaks) is unique in the epic of creation, probably induced by the personification of Tiamat. In other texts Apsu is used in the objective/impersonal sense as the ‘underground water’, representing the depot of precipitation and mineral water, something that can be reached by digging a hole. It is the domain of the (water)god Ea, who controls this water supply. The Apsu feeds the rivers with respect to their continuous water supply. The seasonal changes and the precipitation itself are the domain of the (weather)god Adad; Ea and Adad both are responsible for the fertility of the fields. On cylinder seals one sees the Apsu as a shrine with Ea seated on his throne with running water aside.

The Apsu borders the underworld, the residence of the deceased, the domain from which no return is possible. In other contexts Apsu is sometimes equivalent with the underworld.

Tiamat and Apsu create their offspring. Apsu is called the begetter of the great gods in line 29 of tablet I. The first pair of children are

Lahmu and Lahamu. These names (‘the hairy one’ or ‘muddy’) known in Sumerian times in the 21st century BC (texts of Gudea, Cylinder A). They have three pairs of curls. Lahmu is the gatekeeper of the Apsu, seen as the domain of the god Ea (Sumerian Enki). In other texts there are more Lahmu‘s, sometimes 8, but also 50. Gudea (on lay Cylinder cylinder A) speaks about 50 Lahama’s of the engur (approx. syn. with abzu). This large number is in this creation epic Enüma elish reduced to the pair Lahmu and Lahamu (man and wife? It is not written down!) because of the analogy in this theogony to other pairs.

Anshar and Kishar Sumerian an ‘sky’, ‘heaven’. Anshar (masculine) ‘whole sky’ paired with Kishar (Sumerian ki ‘earth’) is presented as father of the heaven god Anu.

(to be continued)

Explanation of the first lines

For cuneiform text and transcription click here,

And

see translation in English.

A

translation of all tablets is given elsewhere on the net.

I.1

e-nu-ma e-lish la na-bu-ú shá-ma-mu

enüma elish lä nabû shamämü

e-nu-ma e-lish la na-bu-ú shá-ma-mu

enüma elish lä nabû shamämü

‘When above heaven was not (yet) named’

Enüma is the temporal conjunction ‘when’; also inüma and inu.

I use ï, ä, ü to indicate long vowels for lack of anything better within the htm-limitations. They are usually written with a macron on top of the vowel.

sh denotes the letter shin as in shashlick

Contracted vowels are transcribed with circonflex, like in many languages. They are pronounced as a long vowel as compensation for the lost consonant. E.g. French hôpital (long o, < hospital with lost s).

elish is an adverb formed with the ending -ish and associated with elû which is (as verb) ‘to be high’, as adjective ‘high’.

lä is the negation ‘not’, here with a verb in the so called stative form.

nabû <nabiu is a verb in the stative conjugation ‘to be named’, here in 3rd person singular ‘is/was named’ which happens to be identical to the infinitive.

shamämü is a literary form of the plural shamä’ü or shamû ‘sky’, ‘heaven’

I.2

shap-lish am-ma-tum shu-ma la zak-rat

shaplish ammatum shuma lä zakrat

‘(and) below the earth was not pronounced by name’

shaplish ‘below’ is an adverb formed with the ending -ish from shaplu ‘under’, ‘lower side’.

ammatum is a (rare) literary word for ‘earth’; the ending -atum is nominative feminine. It is apparently a feminine word and has the nominative case because it is subject.

shuma is the accusative case for shumu ‘name’; it is object in this phrase.

zakrat is a stative form of the verb zakäru(m) ‘to speak’. In the static sense translated as a passive: ‘is pronounced’. The form of the verb is 3rd person feminine, because the subject ‘earth’ is feminine. In Akkadian some verb conjugations discriminate between masculine and feminine.

‘Above’ and ‘below’ are often used to indicate ‘heaven’ and ‘earth’, but sometimes also ‘earth’ (or ‘the world of the living’) and ‘underworld’ (or ‘the world of the dead’) as a contrasting pair. In combination it could mean ‘everywhere’.

I.3

zu.ab-ma resh-tu-ú za-ru-shu-un

abzu-ma rështû zärûshun

‘and Apsu, the first one/the ancient Apsu, their begetter

logogram zu.ab, Sumerian Abzu, Akkadian Apsu extended with an enclitic particle -ma. This particle has more functions, but here it has conjunctive force ‘and’, which (unlike the simple coordinating conjunction u ‘and’) implies a temporal or logical sequence between two clauses. It may often be translated ‘and’, ‘and then’, but other translations may be required by the context.

rështû < rështiu ‘eldest (son)’, ‘first born’, ‘ancient’; the -t- is not a ”feminine -t-” but part of an ending -tiu that makes here an adjective out of a noun stem. The meaning is related to rëshu ‘head’, ‘front part’, ‘upper part’, ‘beginning’.

The contracted and therefor long vowel at the end is here spelled explicitly with an extra ú as resh-tu-ú

zärûshun < zäriu+ suffix shun ‘their’.

zäriu or zëriu is ‘begetter’, ‘offspring’, It is a participle. The participle normally functions as a noun and indicates ‘the person who…’, ‘he who …’.

The possessive pronouns ‘my’, ‘your, ‘his’,…’their’ are in Akkadian expressed as a suffix.

The 3rd person singular ‘his’ is in Old Babylonian texts usually -shu, but in later times (as here in this text) often written as shú (shu2).

The 3rd person plural ‘their’ is -shunu often spelled as shu-nu or shú-nu, but here we see the short (apocope) form -shun, spelled as -shu-un.

I.4

mu-um-mu ti-amat mu-al-li-da-at gim-ri-shú-un

Mummu Tiämat mu(w)allidat gimrishun

‘(And) maker Tiamat, who bore them all’

logogram for amtu ‘virgin’ and has only in the combination with ti the phonetic value amat to form the proper name Ti-amat.

Mummu ‘clever person’, ‘a person of genius’; it is a proper name, the craftsman god, Apsu’s vizier, usually used as an epithet of the wise god Ea/Enki (later in the text it is explained why). The word is here used as something like ‘maker’.

mu(w)allidat is a participle in the socalled D-stem of the verb. The infinitive in the basic stem is (w)alädu (the w in Old Babyloninan time is later falling off). It means (in both stems) ‘to bear’. The D-stem often indicates the factitive (expressed with ‘to make …’, e.g. the D-stem of ‘to be good’ is ‘to make good’).

The participle is ‘she who bears’, ‘begetter’. The participle in all other stems except the basic stem, is formed with the prefix mu-. In the D-stem (D from doubling) the middle radical (the middle consonant of the root) is doubled (here l). The ending -at is for a feminine participle. It is here in the construct form (e.g. no case endings like -um) because it is followed by a noun in the genitive.

gimru is a noun indicating ‘totality’, here in the construct state genitive gimri- followed by a possessive suffix -shun ‘their’, litt.: ‘their totality’. Forms of gimru are often translated with words like ‘all’, ‘entire’.

I.5

a.mesh-shú-nu ish-te-nish i-hi-qu-ú-ma

mêshunu ishtënish ihïqüma

‘(and when they) had mixed their waters together’

a.mesh is logogram for mû ‘water’ (a plural form, as indicated by the logogram mesh for plural), here in the accusative case (object of ‘to mix’) mê with an added suffix for the possesive pronoun -shunu ‘their’, here not in abbreviated form.

ishtënish an adverb ‘first’, ‘equally’, also: ‘together’

ihïqü present tense (3rd person plural ‘they’) of the verb with infinitive hâqu < hiäqu ‘to mix’

The prefix i- is characteristic for the 3rd person, the ending on long -u marks the plural: ‘they’ (the subject is Tiamat and Apsu). It is the present tense of the ongoing action ”while they mixed”, so it is not translated in the present tense.

The background of the expression ”mixing their waters” may be as follows: Tiamat is the personification of the sea and the salt water, while Apsu represents the fresh water. The mixing symbolizes the proces seen in the marshes of the southern part of Mesopotamia (the area where presently the remaining marsh-Arabs are hiding and in the past the culture of the Sumerians had prospered). In the mixing of these waters reed grows. At first floating islands are formed, which are ultimately transformed into new and fertile land, that brings prosperity.

I.6

gi-pa-ra la ki-isc-scu-ru scu-sca-a la she-’u-ú

gipa(r)ra lä kiscscurü scuscä lä she’û

‘(but when) pastures were not (yet) formed , nor reed-beds were made’

I denote the letter tsade as sc, the emphatic s; it is usually written with a dot under an s. A double tsade becomes scsc, a little bit awkward, I admit.

stand for the letter ‘aleph’ in any combination of any vowel, so it could be a’, e’, i’, u’ or ‘a, ‘e, ‘i, ‘u

giparu or giparru is ‘pasture’, here object (in accusative case with ending -a)

kiscscurü < *kitscurü (the so called t-infix which marks a special stem, the Gt-stem, is here assimilated to the following tsade to form a double tsade)

This verbal conjugation is the stative (either 3rd person plural or as subjuntive, in a relative clause depending on enüma) in the Gt-stem. The basic infinitive is kascäru ‘to twist’. The Gt-stem often adds ”iterative” meaning to the action described in the verb. Since ‘to twist’ is already an ”iterative” action, this verb often appears in the Gt-stem. ‘to twist a pasture’ in the sense ‘to make/form/create a pasture’.

A stative should formally not appear with an object (such as ‘pasture’ here). In this literary text, however, one often finds such a transitive stative. They have the meaning of a present or preteritum tense.

scuscû ‘marsh land’, ‘reed beds’

she’û means ‘to search’, also 3rd person stative as subjunctive or plural: ”when reeds were not searchable”

I.7

e-nu-ma dingir.dingir la shu-pu-u ma-na-ma

enüma ilü lä shüpû manäma

‘When none of the gods were (yet) manifest,

logogram dingir.dingir is plural ilü ‘gods’, nominative (subject)

shüpû is the stative 3rd person plural in the Shin-stem of the verb (in basic stem) wapû ‘to manifest’, ‘to become visible’; meaning in the Shin-stem: ‘to make visible’, ‘to glorify’; stative: ‘being made visible/manifest’

manäma ‘somebody’ (also manamma, mamman) and with the negation lä ‘nobody’, ‘not one of …’, here a aposition to ‘gods’: ‘none of the gods’

[

Back to main Index]

[

Back]

To the chapters [

Main Index] [

Intro] [

Mesopotamia] [

Texts] [

Cuneiform] [

Language] [

Books] [

Links]

.

Prologue to the Codex Hammurabi,

details on the first few lines

See cuneiform text

in New Assyrian form and transcription

The prologue of the Codex Hammurabi (approx. 1850 BC) describes how Hammurabi, ruler of a great empire in the Ancient Middle East in the Old Babylonian time, obtained the Laws from the gods.

(Moses, a millennium or so later, was not the only one who got his laws from god).

The structure of the prologue is basically one main sentence, with many subordinate clauses. The verb in Akkadian comes at the end and the verb of the main sentence appears in tablet V line 23. The dependent clauses in between are often epithets describing the deeds of the gods and the good works of Hammurabi. Without the dependent clauses the prologue is simple:

‘I, Hammurabi, established:’ (followed by the actual codes)

With the notation for tablets and line numbers, the structure of the first introducing clause is

- I.1 When (the gods Anum and Enlil) …..,

I.27 when (they elected) me, Hammurabi, ……,

I.49 they elected;

I.50 I, Hammurabi, ……..,

V.23 I established

V.24 and I let the people prosper

V.25 Then:

(and hereafter follow the Codes of Law)

One of the first things to do with a text is searching for the verb at the end of a clause.

Explanation of the first few lines

| I.1 |

|

|

|

|

ì-nu |

AN |

sci-ru-um |

|

inu |

Anum |

Scïrum |

|

When |

Anum, |

the sublime, |

Anum, Sumerian AN, is the supreme god, god of heaven;

inu is the temporal conjunction ‘when’; later (as in the Enüma eli epic) it is enüma or inüma;

epic) it is enüma or inüma;

Sc here stands for tsade, the emphatic s, usually written with a dot under the s;

I use ï, ä, ü to indicate long vowels for lack of anything better within the htm-limitations. They are usually written with a macron on top of the vowel;

AN has more meanings but is here logogram for the god Anum, which is in this case the same word as the Sumerian name AN plus the usual Akkadian ending -um is added (-um is the ‘default case’ and also masc. nominative singular).

| I.2 |

|

|

|

|

LUGAL |

d. |

A-nun-na-ki |

|

ar ar |

|

Anunnaki |

|

‘King of the Anunnaki’ |

Anunnaki, a Sumerian loan word, is here the collective name for all the gods. The word carries the determinative d for deities. It is used sometimes interchangeably with ‘Igigi’. In other texts the gods are divided into gods of heaven (‘Igigi’) and gods of the underworld (‘Anunnaki’).

ar (where

ar (where  denotes the letter shin as in shashlick) is the so called construct state of the noun

denotes the letter shin as in shashlick) is the so called construct state of the noun  arrum ‘king’. The construct state is used when the noun is followed by a noun in the genitive or by a possessive pronoun. (Anunnaki is a virtual genitive: you can’t see it from the form (case endings) because proper names are often not declined), e.g.

arrum ‘king’. The construct state is used when the noun is followed by a noun in the genitive or by a possessive pronoun. (Anunnaki is a virtual genitive: you can’t see it from the form (case endings) because proper names are often not declined), e.g.

- ‘Landlord’ would in Akkadian be written as ‘lord land’, with ‘lord’ in the construct state and ‘land’ in the genitive.

ar

ar  arrï (with long i, here written as ï, the genitive masc.plural)

arrï (with long i, here written as ï, the genitive masc.plural)

‘king of the kings’

The form of the construct state often is the shortest form of the noun which is phonetically possible.

The logogram LUGAL for  arrum ‘king’ (nominative case) could also be used for other cases (genitive or accusative), and also (as here) for all cases of the construct form.

arrum ‘king’ (nominative case) could also be used for other cases (genitive or accusative), and also (as here) for all cases of the construct form.

| I.2 I.3+4+5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d. |

En-líl |

be-el |

a-me-e a-me-e |

ù |

er-Sce-tim |

|

d. |

Enlíl |

bël |

amê amê |

u |

erScetim |

|

|

‘(and) Enlil, |

lord of |

heaven |

and |

earth’ |

bël is the construct state of bëlum ‘lord’ and is followed by the genitive of  amû ‘heaven’, ‘sky’ and erscetum ‘earth’.

amû ‘heaven’, ‘sky’ and erscetum ‘earth’.

The word for ‘heaven’ is a contraction from  amä’ü with two long vowels and an aleph in between. It is plural. Contracted vowels are transcribed with circonflex, like in many languages. They are pronounced as a long vowel as compensation for the lost consonant. E.g. French hôpital (long o, < hospital with lost s).

amä’ü with two long vowels and an aleph in between. It is plural. Contracted vowels are transcribed with circonflex, like in many languages. They are pronounced as a long vowel as compensation for the lost consonant. E.g. French hôpital (long o, < hospital with lost s).

u is a word by itself ‘and’. It is here written as u3, but one could also encounter

-

u2, or

u2, or

u (rarely)

The word for ‘heaven’ and ‘earth’ is written phonetically, but is often represented logographically with

- AN ‘heaven’ and KI ‘earth’,

also elsewhere in the Codex.

Enlil is the sky-god. The gods Anum and Enlil are both supreme gods, king of heaven and earth. In tables of deities they are listed first in hierarchy, followed by the mother goddess and three astral gods Sin (Moon), Shamash (Sun) and the goddess Ishtar (Venus).

In pictures Anum and Enlil carry 10 pair of horns, the same emblem for both of them: in the world of the gods Kingship is shared. In some texts (like this one here) there appears a division of tasks, where Anum is King of the gods and Enlil is Lord of heaven and earth. In mythology Anum is a somewhat dim personality, whereas Enlil has a definite character, central in many epics.

| I.6+7 |

|

|

|

|

a-i-im a-i-im |

i-ma-at i-ma-at |

KALAM |

|

ä’im ä’im |

imät imät |

mätim |

|

who decreed |

the fates of |

the land |

ä’im is the (active) participle of the verb with infinitive

ä’im is the (active) participle of the verb with infinitive  iämum or

iämum or  âmum ‘to decree’; the participle normally functions as a noun and indicates ‘the person who…’, ‘he who …’. It is here in the construct state (nominative ending -um falling off), because it is followed by a combination of construct state plus genitive.

âmum ‘to decree’; the participle normally functions as a noun and indicates ‘the person who…’, ‘he who …’. It is here in the construct state (nominative ending -um falling off), because it is followed by a combination of construct state plus genitive.

imät is the construct state of the fem. plural form

imät is the construct state of the fem. plural form  imätum of

imätum of  imtum ‘fate’.

imtum ‘fate’.

KALAM is logogram for mätum ‘land’, here as a genitive ‘of the land’.

An important task of the supreme god Enlil is to decree the fates of mankind (kings, ordinary people, countries etc.). The fates have been determined in the assembly of the gods, presided by Enlil.

To the chapters [

Main Index] [

Intro] [

Mesopotamia] [

Texts] [

Cuneiform] [

Language] [

Books] [

Links]

Akkadian Cuneiform, Chapter I Introduction

Chapters: [Intro] [Mesopotamia] [Cuneiform texts] [Writing system] [Akkadian language] [Books] [Links]

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Mesopotamia

Intro

Prehistory

Protohistory

Bronze Age

Iron Age 3. Cuneiform texts

Edubba Trajactina

Enuma elish

Codex Hammurabi 4. Writing system

Origin

Clay tablets

Physical appearance

Sign values

Sign Lists 5. Akkadian language

Intro

Semitic lang.

Dialects

Grammar

Dictionaries

6. Books

7. Links