El Palacio de Topkapı (Topkapı Sarayı en turco, literalmente el ‘Palacio de la Puerta de los Cañones’ — por estar situado cerca de una puerta de ese nombre), situado en Estambul, fue el centro administrativo del Imperio otomano desde 1465 hasta 1853. La construcción del palacio fue ordenada por el Sultán Mehmed II en 1459, y fue completada en 1465. El palacio está situado entre el Cuerno de Oro y el Mar de Mármara, y desde él se tiene una espléndida vista del Bósforo. Está formado por muchos pequeños edificios construidos juntos y rodeados por cuatro patios.

Sultan Mehmed II ordeno la h. 1460s

El palacio está construido siguiendo las normas de la arquitectura seglar turca, siendo su máximo ejemplo. Es un entramado complejo de edificios, unidos por patios o jardines siendo la superficie total del complejo de 700.000 m², rodeados por una muralla bizantina.

Modelo del palacio de Topkapı hacia los siglos 17th -18th que se exhibe en el mismo palacio.Modelo a escala del Serrallo con el complejo del Palacio de Topkapı

En 1853, el Sultán Abdulmecid decidió trasladar su residencia al recién construido y moderno Palacio de Dolmabahçe. En la actualidad, el Topkapı es un museo de la época imperial, siendo una de las mayores atracciones turísticas de Estambul.

00000000000000000000000000000

Para los extranjeros, el Palacio Museo de Topkapi es una de las principales atracciones de Estambul. Las fabulosas colecciones de joyas, porcelanas europeas y chinas, armas, vestimentas históricas y vajilla confirman el esplendor que siempre se asocia con el Imperio Otomano.

Modelo de Palacio de Topkapi,Estambul

Conviene reservar todo un día para una visita detallada del museo y hasta se puede almorzar en él. Hay un restaurante y una cafetería desde los que se tiene una magnífica vista del Bósforo.

Tetera de oro y piedras preciosas

Asimismo, es conveniente referirse a las distintas secciones del palacio en sendas notas. La parte más célebre de Topkapi, aquella a la que se precipitan todos los visitantes, es el legendario tesoro.

Los objetos que se encuentran en él consisten en botines de guerra, trofeos, regalos, piezas que pertenecieron a los grandes dignatarios, a los visires, a los emperadores, muchas de ellas realizadas por los orfebres del palacio.

Después de la derrota infligida al sha Ismail por Yavuz Selim I y de la conquista de Egipto llegaron a Estambul los gobeletes y brazales de oro de Ismail, así como los candelabros de los mamelucos del siglo XIV y los espejos de la época seldjukide. Entre las reliquias religiosas se halla el supuesto cráneo de San Juan Bautista guardado en un relicario de oro.

Obsequios fabulosos

De los regalos, ofrecidos a los sultanes, se destaca el trono que le envió Mahmut I (1730-1754) al sha Nadir de Irán. Cuatro pies, en verdad casi columnas de balaustrada, en forma de floreros soportan el asiento alargado; los lados son redondeados y salientes. El trono está hecho en oro y adornado con piedras preciosas (rubíes, esmeraldas, diamantes) y delicados detalles de esmaltes.

Hay más tronos notables en exhibición. El visir Ibrahim Pacha le hizo hacer al bey Misirli Dervis uno para que se lo regalara al sultán Murad II. Está hecho en madera de nogal y recubierto de diez placas de oro que pesan en conjunto 250 kilos y están incrustadas con 954 olivinos.

Una de las piezas más importantes de Topkapi es el diamante Ksikci Elmasi. Tiene forma de pera, pesa 86 quilates y está montado en una doble hilera de 49 brillantes. El diamante mide 7 centímetros por 6 y está protegido por una placa de plata recubierta de oro.

0000000000

The entire length of the dagger is about 35 cm, inclusive of its handle. The curved blade of the dagger alone may be just over two-thirds of its length, and closely fits into curved sheath. The sheath is made out of gold with enameled flower motifs and encrusted with diamonds. The enameled flower motif at the center of the sheath represents a bouquet of flowers placed in a vase. The diamonds encrusted on the sheath also form a design on either side of the enameled flower motif, one towards the base and the other towards the tip of the sheath. The diamond motif at the base of the sheath consists of 31 diamonds, mostly rectangular in shape arranged in a symmetrical pattern. The other diamond motif towards the tip of the sheath is made up of 21 diamonds, also placed symmetrically. The tip of the curved sheath is occupied by a large emerald.

Overall the emerald dagger and its enclosing sheath represent a masterpiece of the highest artistic traditions, and the art of jewelry making, that reached a highly refined status in the 17th century Ottoman Empire. A diamond-studded gold chain attached to the handle of the dagger enhances the ornamental value of this artistic creation.

Gigantesco broche de esmerala y perlas del Tesoro del Imperio Otomano Topkapi palace museum, istanbul, turkey

Topkapi Palace built by Sultan Mehmet II between 1465 and 1479

The Topkapi Palace was the palace and the main administrative center of the Ottoman empire for 400 years from the 15th to the 19th centuries. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmet II shifted the capital of his empire from Edirne to this city, which came to be known as Istanbul. Sultan Mehmet II at first built his palace at a site which is now occupied by the University of Istanbul. Subsequently in the year 1465, he ordered the construction of a new palace at point Seraglio, overlooking the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara, the site of the ancient Acropolis of the Byzantine empire. The palace was completed in 1479, and occupied by Sultan Mehmet II in the same year, and was referred to as the “New Palace,” the palace which he earlier occupied being known as the “Old Palace.”

Estatua de perla, Museo Topkai,Estambul

The Topkapi Palace served a dual function both as the residence of the Sultan and the main administrative center of the Ottoman empire

Floor plan of Topkapi palace

- A The first court

- B The second court

- C The third court

- D The fourth court

- 1 The middle gate (gate of greeting)

- 2 The kitchens (Chinese and Japanese Porcelain - Silverware)

- 3 The hall of Divan

- 4 The tower of justice

- 5 The armoury

- 6 The gate of Felicity

- 7 The Throne room

- 8 The costumes

- 9 The treasury

- 10 The Miniature painting collection

- 11 The clocks

- 12 The Pavilion of the Blessed Mantle

- 13 Mecidiye Pavillon

- 14 Iftariye (breakfast) and Baghdad Pavilion

- 15 The Harem

The “New Palace” which was one of the most magnificent palaces ever built, eventually came to be known as the “Topkapi Palace” after the installation of the huge cannons outside the main gate of the palace. Unlike other palaces in the western monarchies, the “Topkapi Palace” served not only as the residence of the Ottoman Sultans and their families, but also as the center of Government of the Ottoman empire where the cabinet of ministers met. Besides the palace also housed the various ministries of the government, the imperial treasury, the imperial mint, the imperial archives, and advanced educational institutions of the government that trained civil servants, managers and accounting officers for different government institutions. Civil servants who graduated from this school were posted to the far flung corners of the vast empire where they served the Sultan and his empire faithfully and helped in the administration of the vast domain. Most of the viziers and grand viziers were graduates of this administrative school.

In other words the Topkapi Palace was the vital nerve center of the highly centralized administrative structure of the vast Ottoman empire, one of the most powerful and sophisticated empires in the world, which at its height ruled the entire Balkans, Hungary, Crimea, the Arab East, North Africa, and at times parts of Italy, Poland and Ukraine. The Turks in their long and ancient history founded 16 empires, but the Ottoman empire was the largest, most successful and long lasting of all, that existed for 622 years, exercising its benevolent governance on peoples of European, Asian and African lands in the neighborhood of the Mediterranean and Black seas. The empire was governed by 36 sultans during its existence, and beginning from the early 16th century the sultans also became the spiritual heads of the Islamic world as caliphs. During this period the Topkapi Palace and its neighborhood, and the City of Istanbul became a cosmopolitan environment, where people of different ethnic groups, speaking different languages and professing different religions, from the far corners of the empire, lived and worked together in peace, creating a culturally dynamic society, that was responsible for the creation of the architectural and artistic marvels of this period, which attained a very high state of refinement.

The Topkapi Palace, a lasting monument to the typical Turkish palace architecture

The Topkapi Palace is a typical example of Turkish palace architecture. The most distinctive feature of this architecture is a series of tree-shaded open courtyards, each meant for a particular purpose, and interconnected by large and impressive gates. The periphery of the courtyards are occupied by buildings that perform various functions of government. Ever since the palace was built in the 15th century, it has undergone constant development and expansion, as each sultan, depending on his tastes, made his own alterations and additions. The “Harem” consisting of about 400 rooms was constructed only a century later during the reign of Sultan Murad III. Keeping pace with the expansion of the palace, the number of residents in the palace also dramatically increased. Initially the number of residents in the palace were about 700 to 800, which rose to about 5,000 towards the latter period of the empire, rising to nearly 10,000 during periods of festival. The Janissaries, the elite corps in the service of the Ottoman empire, constituted the largest part of the palace population, and were based within the first courtyard of the palace. Thus the Topkapi Palace with a total area of 700,000 meter square and surrounded by a wall of 5 km became the largest palace in the world.

Abandoning of the Topkapi Palace in 1853. Restoration of the Topkapi Palace and its conversion to a national museum

In 1853, after the construction of the new Dolmabache (filled up garden) palace by Sultan Abdul Megid, Topkapi’s importance as the official royal residence diminished, and the palace was almost abandoned. Deterioration set in and parts of the enormous palace began to crumble. Finally after the demise of the Ottoman empire following its defeat in World War I, Turkey was proclaimed a republic on October 29, 1923, and Mustafa Kemal Ataturk became its founder president. President Ataturk realizing the importance of preserving the national heritage of Turkey, ordered the preservation and restoration of all sites of historical and archaeological importance. Under this plan the restoration of the Topkapi palace was given pride of place, and Ataturk ordered that the ancient palace be converted into a national museum. After almost five decades of restoration work, the Topkapi palace has now been restored to its former pristine glory, and houses one of the world’s largest collection of artworks and artifacts, which include ceramic, glass and silver ware, imperial costumes, arms and armor, miniatures and manuscripts, clocks, gold and silver jewelry set with precious stones, jewel encrusted objects like daggers, jewel encrusted thrones, rough emeralds and other gemstones etc.

The First Courtyard of the Topkapi palace

The Imperial Gate or Bab-i-Humayun

The main entrance to the first and outermost courtyard, known as the “Courtyard of the Regiments” is through the Imperial gate known as Bab-i-Humayun. The portal of Bab-i-Humayun is flanked by two towers built during the time of Sultan Mehmet II. In the past the severed heads of traitors were displayed at the gate. The portal was guarded by a special regiment of palace guards. However, the general public could have access through this gate as the first courtyard was open to the public.

Fountain of Sultan Ahmed III

The fountain just outside the gate is the fountain of Sultan Ahmed III, which is the most striking example of 18th century “Meydan” fountains.

The service buildings, the tiled pavilion, the archaeological museum, Haghia Eirene church

Around the periphery of the first courtyard were the service buildings, which included a hospital, bakery, mint, accommodation for palace servants and guards and the firewood depots. There was an area in the first courtyard that was reserved for cultivating vegetables, which were supplied to the palace. A building of significance in this courtyard was the Cinili Kosk (the tiled lodge or pavilion), the first building constructed in the Topkapi palace complex, and which is now a ceramics museum, exhibiting Turkish ceramics from the 12th century to the present day. Next to the tiled pavilion is the Archaeological museum which houses one of the most outstanding collections in the world, and consists of archeological exhibits dating from ancient Byzantine period. Another building of historical importance is the Haghia Eirene, a 6th century Byzantine church which was converted into a military museum, and later restored and used as a concert hall because of its excellent acoustics. An ancient Gothic Column from the Byzantine period erected in the 3rd century A.D. is also preserved in the first courtyard.

m info :

Historical Background on the Topkapi Palace

Museum contact and visitor’s information

Books and documents about Topkapi Palace Museum

Guide to Topkapi Palace

Main sections :

Harem

Palace attire and garments

Imperial Treasury

Books, Maps and Calligraphic documents.

Miniatures from the Topkapi Museum.

Portraits of the Sultans.

Clocks

The chambers of the Sacred Relics

Porcelains in the Topkapi Museum

Guns and Armory

Various Sections of the Topkapi Palace

Links to related sites

Home

Layout of the Topkapi Palace Museum

A The first court

B The second court

C The third court

D The fourth court

1 The middle gate (gate of greeting)

2 The kitchens (Chinese and Japanese Porcelain - Silverware)

3 The hall of Divan

4 The tower of justice

5 The armoury

6 The gate of Felicity

7 The Throne room

8 The costumes

9 The treasury

10 The Miniature painting collection

11 The clocks

12 The Pavilion of the Blessed Mantle

13 Mecidiye Pavillon

14 Iftariye (breakfast) and Baghdad Pavilion

15 The Harem

The Second Courtyard

Babus-selam or the “Gate of Salutation”

From the first courtyard, entry to the second courtyard is gained through the gate known as the Orta Kapi or Babusselam which may mean “the gate of greeting” or the “peace gate.” This gate is also flanked by two towers on either side, and today this gate is the formal entrance to the Topkapi museum.

Divan Odasi or the Chamber of State buildings

The administrative center of the state and the government, the “Divan Odasi” or the “Chamber of State” are situated in this courtyard, on the left as one enters through the Babusselam. The “Council of State” met four days in a week under the chairmanship of the Grand Vizier. Other participants at the meetings were the Viziers and their secretaries. The Sultan normally did not participate in the meetings, but had the privilege of listening to the deliberations if he so wished from a high window masked by curtains, in one of the walls separating the council chamber from the Harem. The hall of the “Council of State” was also the venue for the occasional feasts given in honor of visiting foreign missions. The “Tower of Justice” the only tower in the palace grounds, is also situated among the “Council of State” buildings. The tower was so named because justice in the name of the state was dispensed from the buildings surrounding this tower.

The state treasury buildings, a display house for old weapons

The large eight-domed building adjoining the “Council of State” buildings, with broad eaves was the state treasury. Today this building houses an exhibition of a rich collection of old weapons. Armor and weapons on display include those used by the Sultans, the palace guard, the national army, and weapons captured from foreign armies in battle.

Venue for state ceremonies and receptions

The second courtyard was the venue for state ceremonies as well as for receptions for foreign emissaries. The large extent of the second courtyard which had an area of 22 acres, sometimes enabled a crowd of up to 10,000 people to attend these ceremonies. Whenever the Sultan participated in such events the imperial throne was placed at the opposite end of the courtyard, just in front of the “Gate of Felicity”. Perfect silence prevailed during such ceremonies, and as a show of respect the crowds assembled stood up with their hands clasped in front, before the ceremonies started. On normal working days of the week, citizens who had official business to attend to, were allowed access into this courtyard, and so were the representatives of the Janissary Corps on paydays.

The palace kitchens, display area for the world’s largest collection of porcelain ware

On the right periphery of the second courtyard is the row of palace kitchens, with twenty chimneys. It is said that during the period of rule of the Sultans, the palace kitchens employed over a thousand cooks and assistants who cooked and served meals to the different sections of the palace. Today the restored palace kitchens have been converted to an exhibition hall that displays a representative collection of about 2,500 pieces out of a total of 12,000 pieces, the largest collection of porcelain ware , glassware and silverware in the world. The porcelain ware are classified according to their country of origin. One section displays porcelain ware and glassware produced in Istanbul. A second section displays porcelain ware and silver ware originating from Europe. Another section is allocated to the Chinese porcelain collection, which included the unique Chinese celadons, which were said to change color when the food was poisoned. Sections are also allocated to the Japanese porcelain collection and the blue and white, mono and polychrome porcelain objects. The last section of this display was allocated to everyday kitchen utensils, coffee sets and gold-plated copper ware.

The Harem

Harem which in Arabic means forbidden, refers to a restricted area in the palace which is the living quarters of the sultan and his family, which includes his mother, brothers, sons and daughters, his female consorts and their woman servants. Other residents of this restricted area were an elite corps of male guardians who were castrated black slaves from Ethiopia, commonly referred to as eunuchs who acted as servants and administrators of the harem. The sultan’s mother was the sole ruler of the harem, and there was no title in the empire as the “Empress” normally found in western monarchies.

Photo from Istanbul Government Website

The harem consists of long narrow hallways, with about 400 rooms scattered around small courtyards. The part of the harem which was allocated to the mother of the sultan consisted of 40 rooms. Besides the rooms, spacious domed halls, Turkish baths, fireplaces and hearths, pools and fountains and other special halls and rooms are also found in the harem. Over the years the harem had undergone alterations and extensions. A large hall that dates to the reign of Murad III, has a pool filled by fountains and decorated with beautiful 16th century tiles. This hall leads to a small library and the “fruit room” decorated with paintings of fruits and flowers. Two rooms constructed in the 16th century with rich wall decorations and matching stained glass windows, were allocated to the Crown Prince, who according to the laws of succession of the Ottoman empire was the eldest member of the dynasty, instead of the eldest son of the reigning sultan. This gave a sense of security to the children of the sultan, who could live without any fear of assassination. The total floor area covered by the harem is as big as the area covered by the 3rd or 4th courtyards. The harem which is on the left side of the palace, is situated partly to the left side of the rear of the second courtyard and partly to the left of the front side of the third courtyard. The present access to the harem is through the second courtyard via the Divan Odasi or the Chamber of State buildings.

The concubines serving the sultan and his family were selected from the most attractive and healthy young maidens belonging to different races or ethnic groups, some of whom were sent to the sultan as gifts. The girls usually entered the harem at an early age and were brought up by elderly ladies of the harem in a strict disciplinary environment. The girls were taught everything about the rules, customs and traditions of the palace and the rules of protocol in the palace. When the girls had matured into beautiful maidens and were conversant with all the rules of the palace, they were allowed to serve the sultan. Some of these maidens who were able to attract the attention of the sultan and earn his favors eventually end up as his wives. Being human, the wives of the sultan had their jealousies, hatred and rivalries, and vying with each other and being part of intrigues to get closer to the sultan were part of the daily life in the palace. But being matured, intelligent and benevolent individuals the Sultans always adopted an impartial attitude towards their wives, and peace and tranquility usually prevailed in the harem.

The Third Courtyard

Entry to the third courtyard from the second is through the “Babus-sade” or the “Gate of Felicity,” which was guarded by the white eunuchs. The third courtyard was the private domain of the sultan and therefore entry was restricted to the sultan, who normally passed through “Babus-sade” on horseback, and only a favored handful of statesmen and trusted intimates. Important buildings in this courtyard were the throne room, the sultan’s treasury, the sacred relics chambers, the imperial university and the library of Ahmet III.

The Throne Room or the Audience Chamber

The throne room or the audience chamber which was situated very close to the “Babus-sade” was the place where the sultan met high government officials and received foreign ambassadors. The Grand Vizier and members of the Divan came to the audience chamber to present their resolutions to the sultan for ratification. It is said that for security reasons the lower grades of workers in the audience chamber were recruited from deaf and mute persons.

Trono de oro,Palacio de Topkapi, Estambul

The Library of Ahmet III

Just after the audience chamber almost at the center of the courtyard is the library built by Ahmed III in the early 18th century. This building is a typical example of a structure that blends harmoniously the baroque and Turkish architectural styles.

The Imperial University

The buildings on the right side of the audience room were the classrooms and lecture halls of the Imperial University, which was a training school for producing civil servants, who after graduation were posted to positions of responsibility in the government, such as administrators, accounting officers etc. in different regions of the vast empire. The Viziers and Grand Viziers of the government were graduates of this school. The managers of the Imperial school were military officers, who also served the sultan at the same time in various other capacities.

The Imperial Costume Collection

Today the same buildings that served as the Imperial school, houses the Imperial costume section of the Topkapi Palace. These imperial costumes were made of fabric that were woven in the palace looms, and embroidered with silk. gold and silver thread. There are a total of 2,500 of these handmade costumes, that had been preserved carefully in special chests since the 15th century. Truly, the unique collection of the sultan’s wardrobes, is undoubtedly an outstanding collection of its kind in the whole world. Apart from garments other items displayed in this section include silk carpets and prayer rugs used by the sultans.

The Treasury

The former treasury of the sultan has been converted today to the treasury of the Topkapi Museum, which houses in its four rooms the most valuable collection in the museum, which include jewels and jewelry, jewel-encrusted thrones, jewel-encrusted daggers and other objects, enameled objects etc. This collection is undoubtedly one of the richest collections of its kind in the world. Besides masterpieces of the Turkish art of jewelry manufacture belonging to different periods, exquisite jewelry creations from Europe, India and the far east are also found in this collection. In each one of the four rooms or salons where the collection is exhibited an Imperial throne of a different era is also included.

Cuna de oro

Trono de Ahmed I

The throne was the work of the architect of Sultanahmed mosque, Mehmet Aga.

Room I

Important exhibits in the first room of the treasury include the following:-

1) The complete battle armor of Sultan Mustafa III, made up of iron mail that afforded full protection to the wearer from head to toe, and also included his sword and shield and foot gear for his mount. The battle dress was encrusted with gold and precious stones.

2) Qura’n covers decorated with pearls, including a black velvet cover decorated with pearls and a diamond in the center, with three pearl tassels.

3) The ebony throne of Sultan Murad IV, inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearls and covered with 17th century Turkish hand-woven fabric.

4) The diamond-studded walking stick of Abdulhamid II, that was gifted by Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany.

5) An ornate Indian music box.

6) Turkish and Iranian pots, vases, jugs, sherbet set in gold,

7) Gold candelabras, gold water pipes,

8) Solid jade vases and ports.

Jade tankard with lid

16th century

The throne of Nadir Shah, 18th century.

Irano - Indian. This throne was presented by the Shah of Iran to Mahmud I (1730-1754). Gold, precious stones and enamel embellish the throne.

Sultan’s crest. 18th century.

28cms in height. Bears an emerald (4×5 cms), a ruby (3 cms), and framed by a row of diamonds and pearls.

Room II - Emerald Room

1) Emerald praying beads and arrow quivers encrusted with gold and with flower motifs of diamonds and emeralds.

2) An emerald pendant belonging to Sultan Andulhamid I, with three large emeralds set in a triangle, surrounded by leaf patterns on a gold framework, and 48 strings of pearls forming the tassel.

3) A six-sided pendant set with emeralds, pearls, diamonds and sapphires, on a gold framework, Commissioned by Sultan Ahmet I in 1617.

4) An aigrette with a heavy gold pin encrusted with two 5 cm long emeralds and a garnet, with diamond-encrusted gold leaves and loops of pearls attached.

5) Emerald dagger gifted to Sultan Mehmet IV at the time of dedication of Yeni Mosque. The dagger is 31 cm long with an emerald encrusted handle and a jewel-encrusted gold sheath.

6) Uncut emeralds some weighing up to several kilograms each.

7) The 35 cm long “Topkapi Emerald Dagger” the subject of this web article, a gift to the Persian emperor Nadir Shah by Sultan Mahmud I, but never delivered, as Nadir Shah was assassinated before the embassy carrying the gift reached him.

9) The throne of Sultan Ahmet I, a rare and unique masterpiece of 17th century woodwork executed in walnut and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, tortoise shell and other precious stones.

10) Hand carved works of jade.

11) The golden cradle in which newborn prospective sultans were presented to their fathers, the reigning Sultans. The cradle decorated with flower motifs and encrusted with diamonds and emeralds has dimensions of 103 X 54 cm. A jewel-encrusted pendant overhangs the cradle.

Room III

1) More Qur’an covers decorated with precious stones.

2) A jewel-encrusted gold dessert-set belonging to sultan Abdul Hamid.

3) A pendant carrying the seal of Sultan Mahmud II, encrusted with diamonds, on a blue and pink enamel background.

4) A collection of very famous cut diamonds.

5) Brooches, rings and other jewelry items.

6) A gold tray and gold incense burner.

7) The 86-carat “Spoonmaker’s Diamond” one of the most famous diamonds in the world, set in silver and surrounded by 49 smaller diamonds, which is the most prominent exhibit in this room. Please click here for separate web article on “Spoonmaker’s Diamond.”

8) The twin solid gold candelabras, each weighing 48 kg and decorated with 6,666 diamonds. The set was commissioned by Sultan Abdulhamid.

9) Several medals and decorations, which were gifts from heads of state from around the world.

10) The magnificent Holiday Throne of the Ottoman Sultans, made of gold and encrusted with jewels, used during coronations and religious holidays. The throne that weighs 350 kg was a gift to Sultan Murat III, by the Egyptian Governor Ibrahim Pasha in 1585.

Caja con el sagrado manto de Mahoma

Chests containing the Holy Mantle of Prophet Muhammad and the banner ((Sancak-i Serif).

Espada de Mahoma

http://www.ee.bilkent.edu.tr/~history/topkapi.html

Room IV

1) The most prominent exhibit in this room is the throne of Sultan Mahmud I, a gift by the Persian King Nadir Shah in 1747, just before he was assassinated. The throne with a green and red background encrusted with emeralds and pearls, is a masterpiece of Indian craftsmanship. The throne is also known as the “Peacock Throne” as it has some resemblance to the original “Peacock Throne” of Shah Jahaan, said to be the most splendorous throne ever made in the history of mankind, that was carried away as war booty by Nadir Shah when he invaded Mughul India in 1739. Before leaving India, Nadir Shah also got his unwilling host, the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah, to commission a replica of the “Peacock Throne” using his court artisans, which too he carried away to Iran. It is believed that the “Peacock Throne” in the Topkapi museum treasury, is actually the replica of the original “Peacock Throne” made by Emperor Muhammad Shah at Nadir Shah’s insistence. The original “Peacock Throne” of Shah Jahaan was stolen and dismantled after the death of Nadir Shah, during the period of anarchy that prevailed in the immediate aftermath of his assassination.

2) Swords, rifles, spoons and prayer beads, all extravagantly decorated.

3) The chest in which the mantle of the Holy Prophet Muhammad was once kept.

Portrait and Miniature Exhibit Hall

This hall is located in the building with a colonnade that stands between the Treasury and the Sacreds Relics Chamber, on the opposite end of the courtyard from the Audience Chamber or Throne Room. The museum offices are also located in this building, and a large exhibition hall where temporary exhibitions are organized from time to time.

This section has a rich collection of miniatures, manuscripts, books and writing tools, and some of the rare items have been put out on display. Oil portraits of the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire adorn the walls of the galleries of the hall. The ground floor of the hall displays artwork from the Islamic World from the 13th to 20th centuries.

The Clock Collection

On the same side as the Portrait and Miniature Exhibit Hall, and just adjacent to it, is the hall exhibiting the clock collection. The collection of clocks in this section is perhaps the richest collection of clocks in the world originating from the 16th to 19th centuries. They consist of wall and table clocks and watches of a variety of makes, manufactured in different countries and presented as gifts to the palace. There are also clocks made by Turkish masters. Some of the watches carry the portrait of Abdulmejid and Abdulaziz. A bird cage hanging from the dome displays an enameled clock from its underside. The largest clock in the room, which is of English origin, has a height of 3.5 m and a width of 1.0 m, and contains an organ.

The Sacred Relics Chamber

The Sacred Relics Chamber is located in the domed hall which was previously used as the throne room, before the construction of the new throne room next to the Babus-sade. It is situated directly opposite the treasury on the other side of the courtyard. The walls of the hall are covered with 16 th century Iznik tiles.

Some hairs from the beard of the Prophet Muhammad (Lihye-i Saadet)

Algunos pelos de la barba del profeta Mohamed (Lihye-i Saadet)

The building houses the sacred relics of Islam, brought to Turkey after the conquest of Egypt in the 1517 by Yavuz Sultan Selim I. Among the most important items in this sacred collection are one of the first manuscripts of the Qur’an written on deer skin, authenticated by the Othman the 3rd Caliph of Islam., the keys of the Ka’aba in Mecca, and some personal items and weapons used by the Prophet and his Caliphs. Among the weapons are the swords and the bow of the Prophet Muhammad and his Caliphs.

Among the personal items used by the Prophet is a mantle or cloak used by the Prophet. Other items include the seal of the prophet, a letter written by the Prophet, and some relics from his body such as hairs from his beard, some of his extracted teeth, his footprint and soil from his graveyard. The sterling silver chest that held the sacred relics for centuries is also kept in this chamber.

The Fourth Courtyard

Access from the 3rd to the 4th courtyard is by a passage. The 4th court yard is the rear most section of the Topkapi palace, within which are located several pavilions surrounded by gardens. One pavilion in this courtyard is the “Revan Pavilion” which is the only wooden pavilion in the palace complex, and built by architect Koca Kasim in 1635. The “Baghdad Pavilion” also built by Koca Kasim in 1639 is an octagonal-shaped pavilion much bigger than the “Revan Pavilion.” Between the “Revan pavilion” and the “Baghdad Pavilion” is the circumcision room and the place where the Sultans normally broke their daily fasting at sunset during the month of fasting (Ramazan).

The Mecidiye Pavilion at the right extreme corner of the courtyard was the last addition to the palace.

El harem

Bibliografia

1.The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition - 2008

2.Ottoman Web Site - www. osmanli700.gen

3.Mahmud I - from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

4.The Turkish Journal of Collectable Art - May 1985, Issue 2.

5.Topkapi (film) - From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

6.Overview of Topkapi (1964) - website of Turner Classic Movies.

7.Topkapi Palace Museum - www.ee.bilkent.edu

8.Topkapi Palace - website of the Government of Istanbul

S

El emblema del palacio es el magnífico puñal, conocido precisamente como Topkai . Fue hecho por Mahmud I en 1741 para regalárselo al sha Nadir de Irán. Pero como hubo problemas entre los dos países, la magnífica joya quedó en el palacio. Una de las caras de la daga tiene tres impresionantes esmeraldas ovales de 3 a 4 centímetros, mientras que el reverso del arma está decorada con motivos florales esmaltados y perlas.

La empuñadura está coronada por una tapa redonda formada por una esmeralda octogonal de 3 centímetros de diámetro, se halla bordeada de diamantes y si se la levanta se descubre un reloj que lleva la marca Londres.

La vaina de oro, decorada con motivos florales esmaltados, lleva diamantes incrustados en los dos extremos. Las tres esmeraldas de la empuñadura sorprenden por el tamaño y, en verdad, parecen ser una sola gema de forma irregular, pero muy bella.

Una cuna exclusiva

El público se asombra y hasta se escandaliza cuando se ve frente a una cuna de oro, destinada a los hijos de los sultanes, incrustada con piedras preciosas. Es un mueble tan excepcional por el material precioso con que ha sido realizado como por su función.

Los pendentifs con sus borlas de gemas se cuentan entre las piezas más llamativas del tesoro. Las esmeraldas y los rubíes que componen estas joyas tienen un tamaño descomunal. Uno podría creer que se trata de trozos de mármol, no sólo por las dimensiones y por su aspecto macizo, sino también porque su espesor y su tallado hace que la luz no brille tanto como en las piedras más facetadas.

Mapa de Piri Reis

Las esmeraldas por momentos pueden parecer negras, precisamente por el grosor. De algunos de estos pendientes cuelgan largas hileras de perlas finas. Un hermoso pendentif imperial (nunca se supo quién fue su propietario) está compuesto por una placa de oro, adornada de esmeraldas, rubíes y diamantes, cuyo madroño está trabajado con diferentes piedras.

Hay también un bol de jade firmado por Fabergé y regalado por el zar Nicolás II. En una vitrina se exhibe un estupendo carcaj de oro. Está cubierto de flores en relieve dibujadas con diamantes, rubíes y esmeraldas. Las gemas más grandes son las esmeraldas que forman figuras regulares cuyo centro es la esmeralda mayor del conjunto. Junto a esta pieza excepcional, hay otro carcaj, relativamente más modesto, de terciopelo verde, bordado con diamantes, rubíes y esmeraldas.

Este carcaj fue enviado al sha Nadir en 1746 por Mahmut I y, a la muerte del monarca persa, fue devuelto al soberano otomano. Las exclamaciones de los visitantes en el tesoro merecerían grabarse. Sólo las fabulosas descripciones de las riquezas en los relatos de Las mil y una noches pueden parangonarse con estas joyas que representan a la perfección el refinamiento de la cultura otomana

Actualmente el Palacio alberga un Museo donde se exponen parte de las riquezas del tesoro imperial. Entre los tesoros más espectaculares que encontramos cabe destacar: la sala de las perlas, el puñal más caro del mundo elaborado con piedras preciosas y oro, las pertenencias de Mahoma y el tercer diamante más grande del mundo

Puñál de esmeraldas

A blurry photo (very difficult conditions!) of the Kasikci diamond, on display in one of the treasury rooms of the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, Turkey.

The pride and joy of the treasury room, the central diamond has a weight of 86 carat , and it is surrounded by 49 very large brilliant cut diamonds.

The story goes that it was found in a rubbish bin in Egrikapi during the reign of Mahmed IV (1648-87) and it was brought by a street peddler for three spoons.

A jeweller then bought it, realising its worth then later a dispute arose about the price at which it was sold. The grand vezir Mustafa Pasa heard about the matter and offered to buy it. When the Sultan learned of the matter he brought the diamond to the palace where it was first made into a ring, then later surrounded by the brilliant cut diamonds and made into a turban

El Spoonmaker Diamond’s (turco: Kasikci Elması), el orgullo del Museo del Palacio de Topkapi y el Anexo de más valiosa, como parte de la Tesorería de Imperial, es de 86 quilates (17 g) de pera de diamantes en forma. Surrounded by a double row of 49 old mine-cut diamonds and well spotlighted, it hangs in a glass case on the wall of one of the rooms of the treasury. Rodeado por una doble fila de 49 vieja mina de diamantes talla y bien puesto de relieve, se cuelga en una vitrina en la pared de una de las habitaciones de la tesorería. The surrounding separate brilliants give it the appearance of a full moon lighting a bright and shining sky amidst the stars. Los alrededores brillantes por separado le dan la apariencia de la luna llena en medio de encender un cielo claro y brillante de las estrellas.

Historia

Various stories are told about the Spoonmaker’s Diamond. Varias historias se cuentan sobre el diamante del cucharero Spoonmaker’s. According to one tale, a poor fisherman in Istanbul near Yenikapi was wandering idly, empty-handed along the shore when he found a shiny stone among the litter, which he turned over and over not knowing what it was. Según un relato, un pobre pescador en Estambul cerca de Yenikapi estaba vagando sin hacer nada, con las manos vacías a lo largo de la orilla cuando se encontró una piedra brillante entre la basura, que se volvió una y otra vez sin saber lo que era. After carrying it about in his pocket for a few days, he stopped by the jewelers’ market, showing it to the first jeweler he encountered. Después de realizar sobre ella en el bolsillo de unos días, se detuvo en el mercado de los joyeros “, mostrando que el joyero primero que encontró. The jeweler took a casual glance at the stone and appeared disinterested, saying “It’s a piece of glass, take it away if you like, or if you like I’ll give you three spoons. You brought it all the way here, at least let it be worth your trouble.” El joyero tomó una ojeada a la piedra y parecía desinteresado, diciendo: “Es un pedazo de vidrio, quitar si se quiere, o si quieres te doy tres cucharas. Usted trajo hasta aquí, al menos que sea digno de su problema “. What was the poor fisherman to do with this piece of glass? ¿Cuál fue el pobre pescador que ver con este pedazo de vidrio? What’s more the jeweler had felt sorry for him and was giving three spoons. Lo que es más que el joyero había sentido lástima por él y se den tres cucharas. He said okay and took the spoons, leaving in their place an enormous treasure. Dijo que está bien y se las cucharas, dejando en su lugar un enorme tesoro. It is for this reason they say that the diamond’s name became the “Spoonmaker’s Diamond”. Es por esta razón se dice que el nombre del diamante se convirtió en el “Diamond Spoonmaker’s” o “Diamante del cucharero”.

Según otro relato, la persona que haya descubierto el diamante era una cucharero o fabricante de cucharas por lo que al diamante se le dio este nombre porque se parecía a el cuenco de una cuchara. Incluso hoy, no se sabe cómo este diamante llegó al Palacio de Topkapi, o como se obtuvo . A pesar de que un anillo con una piedra preciosa llamada Diamante delCucharero , que pertenecía al sultán Mehmet IV parece que figura en los registros del museo, esta piedra junto con su oro peso sólo 10-12 g (-10 quilates), que es mucho menor que la Spoonmaker Diamond’s.

Una otra historia es que durante la Batalla de Nicópolis, que que participaron los días 12-13 October 1798 en Preveza, DF, Epiro, Grecia, 700 granaderos franceses de Napoleón el Grande con el General La Salchette, más 200 ciudadanos armados griegos, más 60 griegos contra 7,000 guerreros turco-albaneses de Ali Pasha de Tepelena y su hijo Muhtar.

Los turcos ganaron la batalla, y nueve oficiales franceses fueron detenidos y enviados al sultán Selim III en Estambul. One of the French prisoners was Captain Camus, the 47 years old lover of Napoleon Bonaparte’s mother Letizia Ramolino . Uno de los prisioneros fue el capitán francés Camus, amante de los 47 años de edad de la madre de Napoleón Bonaparte Letizia Ramolino. After receiving the bad news, Letizia has been in contact with Sultan Selim III, and immediately has sent a “Big Diamond” by ship to Preveza as a present for the sultan with the expectation of her lover’s liberation. Después de recibir la mala noticia, Letizia ha estado en contacto con el Sultán Selim III, e inmediatamente envió una “Big Diamond” por barco a Preveza, como un regalo para el sultán, con la expectativa de la liberación de su amante. The diamond went from Preveza to Ioannina and then to Istanbul. El diamante fue de Preveza de Ioannina y luego a Estambul. A history says that Mrs. Vassiliki, wife of Ali Pasha wear the diamond. Una historia dice que la señora Vassiliki, esposa de Ali Pasha usar el diamante. Finally, Captain Camus and the French soldiers had been liberated. Por último, el capitán Camus y los soldados franceses habían sido liberados. Captain Camus’ memoirs are available in three volumes. Memorias de Camus Capitán “están disponibles en tres volúmenes. Informations says that the diamond belonged to Marie Antoinette . Información dice que el diamante perteneció a María Antonieta. As we know, later Sultan Selim III has been murdered and the diamond passed to his successor Mahmud II . Como se sabe, más tarde el sultán Selim III ha sido asesinado y el diamante pasó a su sucesor, Mahmud II.

It has sometimes been suggested that the gem is one and the same as the Pigot Diamond, which was obtained by Lord Pigot in India and brought to London , probably in 1764. A veces se ha sugerido que la gema es uno y el mismo que el diamante Pigot, que fue obtenida por el Señor Pigot en la India y traído a Londres, probablemente en 1764. After a complex history, in which it was disposed of by lottery in 1800, sold a few years later by Christie’s and then offered to Napoleon. Después de una historia compleja, en la que se eliminarán por sorteo en 1800, vendió unos años más tarde por Christie’s y luego se ofreció a Napoleón. It did indeed reach Turkey via Egypt , but the recorded weight of the Pigot Diamond was just 47.38 carats (9.48 g). [ 1 ] Es, efectivamente, llegar a Turquía a través de Egipto, pero el peso registrado del diamante Pigot fue sólo 47,38 quilates (9,48 g). [1]

Los 49 brillantes fueron ordenados o dispuestos, ya sea por Ali Pasha, o por Mahmud II. Estos brillantes le otorgan una belleza adicional a la Diamond Spoonmaker y aumentaron su valor por otro tanto.

El oro, la plata, el rubí, la esmeralda del Tesoro de Palacio de Topkapi no obstante, el Diamante del Spoonmaker hasido el favorito de reinas y madres de los sultanes.

Filed under: ACTUALIDAD,Arte Antiguo,ARTÍCULOS,Ciudades,Costumbres,Curiosidades,Diamante y joyas,Europa,General,H. Próximo Oriente,HISTORIA ANTIGUA,Hombres de la Historia,OPINIONES,PERSONAJES,PERSONALÍSIMO,VIAJES

Trackback Uri

_JPG/642px-Model_Topkapi_Istanbul_(3).JPG)

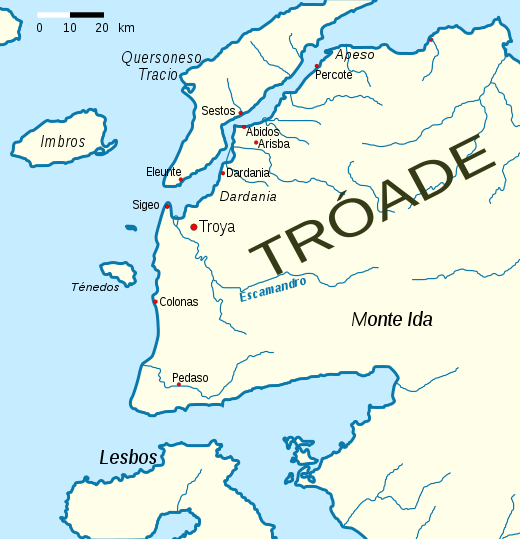

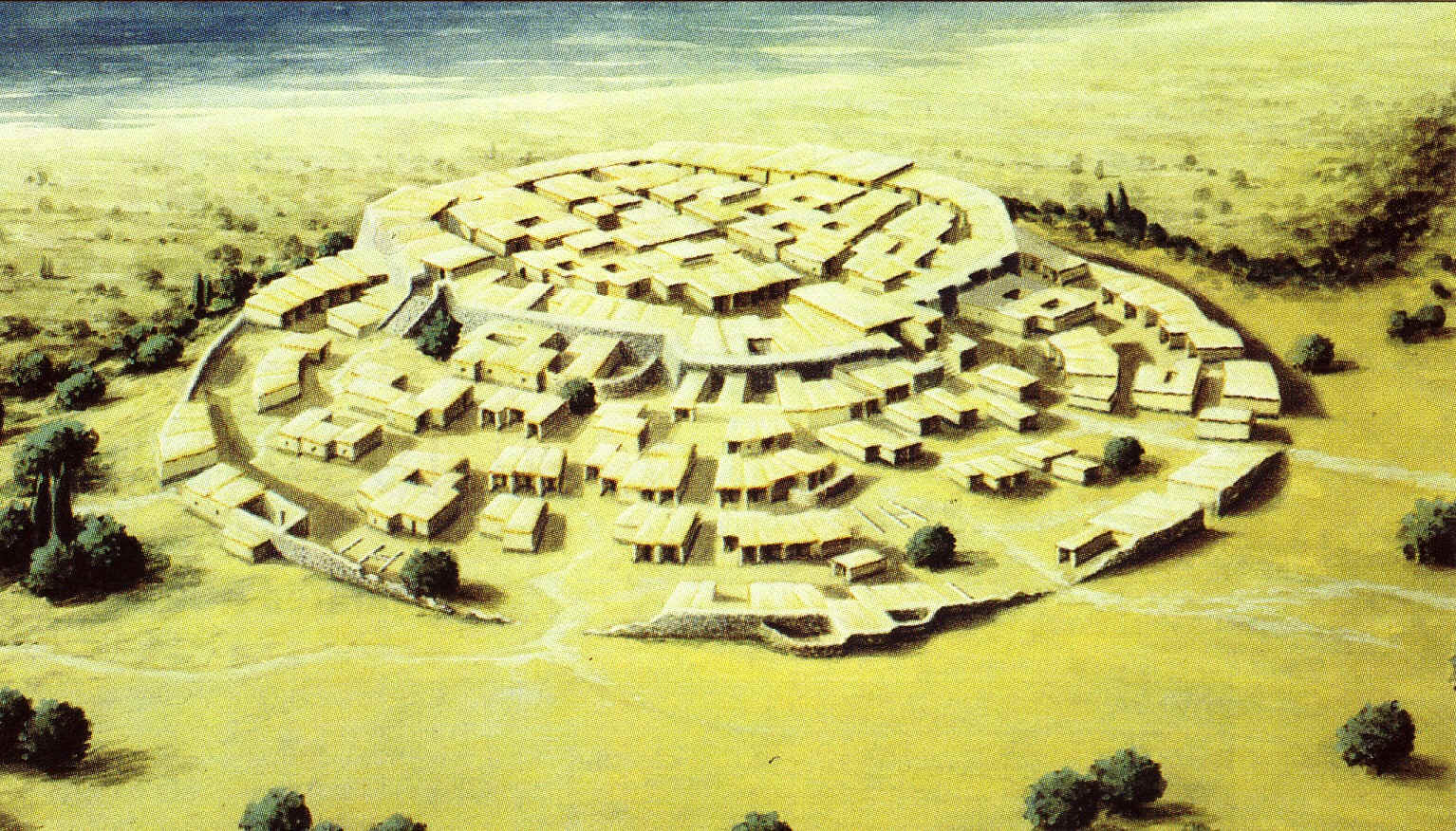

Troya III,reconstrucción

Troya III,reconstrucción