ACHISH

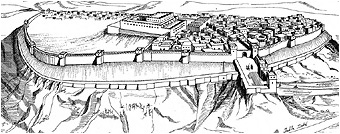

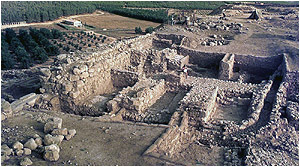

Vista aérea de Lachish,Israel.De frente, la rampa construida por los asirios

Canaán en la época de Josué

www.bible-archaeology.info/cities.htm

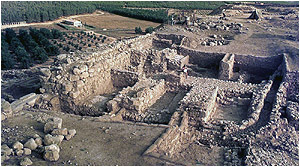

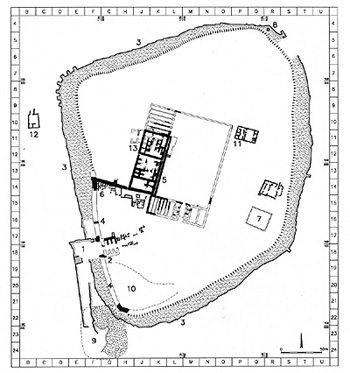

Fig.11 Tell Lachish desde el sur

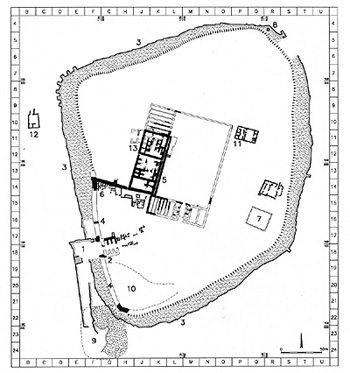

Laquis fue una antigua ciudad de Judá, situada en la Sefelá,[1] e identificada en la actualidad con Tell ed-Duweir (Tel Lakhish), un tell rodeado de valles situado unos 24 km al oeste de Hebrón. Antiguamente Laquis ocupaba una posición estratégica en la ruta principal que enlazaba Jerusalén con Egipto. Su superficie máxima pudo alcanzar las ocho hectáreas, con una población de entre 6.000 y 7.500 personas(Wikipedia).

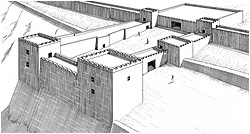

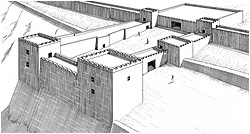

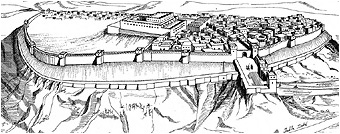

La fortaleza de Laquish estaba rodeada por dos murallas parelelas y una pared externa de revestimiento que rodeaba el sitio en la mitad de la rampa de acceso ,extendiéndose alrededor de la acrópolis o ciudad alta de la ciudad. La pared externa del revestimiento fue descubierta y excavada totalmete por la expedición británica. Solamente su parte más baja, construida con piedras, se habia preservado. Sirvió probablemente principalmente para apoyar una rampa o glacis, que llegaba a la parte inferior de la muralla principal de la ciudad.

Esta muralla estaba construida de ladrillos y la parte baja de piedra. Su ancho era de más de 6 m , proporcionando en lo alto el suficiente sitio para que los defensores se colocasen y luchasen.

La fortaleza, construida según una planificación urbana total, incluía el sistema masivo de los fortalecimientos y de un complejo enorme, el palacio-fortaleza central (fig. 11). Debido a la carencia de inscripciones no se sabe quién fue el rey que construyó la ciudad y en qué fecha. La ciudad amurallada , que comprende los niveles IV e III, continuó sirviendo como fortaleza principal del reino de Judah hasta su destrucción por el rey asirio Senaquerib en 701 a.C. (fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Reconstrucción de la ciudad amuralla de la época del reino de Judá,desde el oeste

Durante la conquista israelita de Canaán, Jafía, el rey de Laquis, se unió a otros cuatro reyes en una ofensiva militar contra Gabaón, debido a que los gabaonitas habían hecho un pacto con las gentes de Israel.[2] A su vez, los israelitas tomaron Laquis y ejecutaron a sus habitantes. Algunos arqueólogos relacionan la campaña de Israel contra Laquis con una gruesa capa de cenizas descubierta en Tell ed-Duweir, donde se halló un escarabeo de Ramsés II, aunque la Biblia no señala que la ciudad fuese incendiada.

Fig. 10. Objetos de metal, uno con un cartucho de Ramses III

http://www.tau.ac.il/humanities/archaeology/projects/proj_past_lachish.html

| .

Una compleja puerta, conectada con ambas partes de la ciudad, permitió el acceso a la ciudad fortificada desde la esquina de sudoeste. Es la puerta más grande, fuerte y masiva que se conoce en Israel.

Había dos puertas en el sistema defensivo de Laquish: la puerta externa, conectada con la pared externa del revestimiento, y una puerta interna, conectando con la muralla principal, y un patio abierto, espacioso entre las dos puertas (fig. 13). Ésta es la puerta que se representa en los relieves asirios (fig. 14). El ala izquierda, norte, de la puerta interna, y los edificios domésticos detrás de ella, se han destapado en las sucesivas excavaciones (área G) (fig. 15). Según lo mencionado anteriormente, el proyecto de la reconstrucción de la puerta se comenzó, aunquese detuvo debido a la carencia de los fondos (fig. 16)

Fig. 14. Ataque de la puerta de la ciudad

|

|

|

Fig. 15. La puerta de la ciudad de época de Judea.La excavación de la puerta desde el sur

Fig. 16. La puerta parcialmente reconstruida

|

|

|

Fig. 17. El palacio-fortaleza judio, desde el sur

El centro de la fortificación estaba ocupado por una gran palacio fortificado,

que servía como centro para la guarnición y de residencia para el gobernador judío (Fig. 17).

Este palacio es sin duda el mayor edificio y más masivo conocido en Judea y se ha excavado

aun muy poco de él. (Figs. 18-19).

|

|

|

Fig. 18. El palacio judío:Esquina sudoeste.

Fig. 19. Palacio judío, cimientos.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Finalmente, un pozo o cisterna de 44 mts. de profundidad ,la mayor fuente de agua de la ciudad ,localizada cerca de la muralla en el esquina noreste (Fig. 20), que proveía de agua en caso de asedio y que aún tenía agua al ser excavadapor el equipo británico.

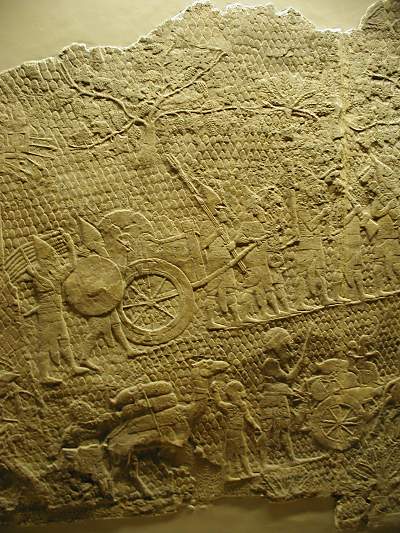

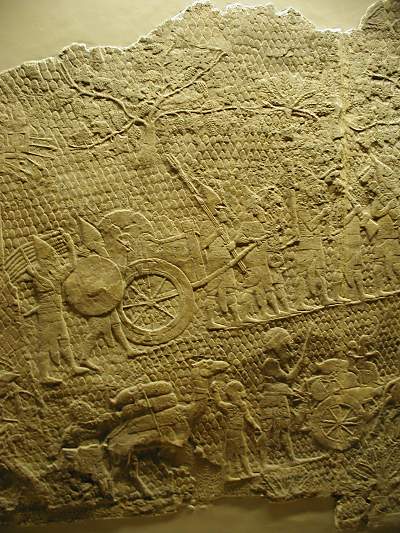

La conquista de Lachish por Senaquerib, rey de Asiria, durante su campaña

de Judah en 701a.C., es única en la historia y arqueología de la época bíblica.

Este dramático suceso es iluminado por el Antiguo Testamento, los relieves y las fuentes asirias y las excavaciones arqueológicas .

En 705 a.C., Senaquerib ascendió al trono de Asiria y se encontró con una revuelta

organizada por Ezequías, rey de Juda. En 701 a.C. , Senaquerib marchó hacia la región y finalmente invadió Juda, centrando su atención en la ciudad de Lachish, la más formidable ciudadela de Juda, y su conquista y destruction mostró a Ezequías el poder asirio.

La ciudad del nivel III fue completamente destruida por fuego en 701 a.C. cuando fue conquistada por el ejército asirio.

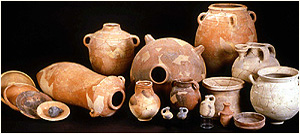

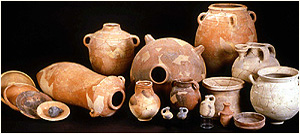

Se ha encontrado una gran cantidad de cerámica en las casas del Nivel III (Fig. 21) entre la que destacan las jarras denominadas real-Judea o lmlk jarras de almacenamiento(Fig. 22).

Fig. 21. Cerámica del Nivel III -final del siglo VIII a.C.

These are large jars, uniform in shape and size, which were manufactured in one production center by the Judean government, as part of the military preparations made before the Assyrian invasion. These jars were used to store oil or wine. They are known from various sites in Judah, but mainly from Lachish. Their handles were stamped.

Fig. 22. Storage jars bearing lmlk seal impressions

The stamps included a royal two-winged or four-winged emblem, and an inscription in ancient Hebrew characters. It reads ‘lmlk‘ that is ‘belonging to the king’ and the name of one of four towns: Hebron, Sochoh, Ziph or Azekah (Figs. 23-24). These towns must have been associated with the manufacture or distribution of the storage-jars, or with the produce stored in them. In addition, some of the jars were also stamped with a ‘private’ stamp with the name of the potter or an official (Fig. 25).

The southwest corner.

When Sennacherib arrived at the head of his army in Lachish, he did not have to deliberate at length on where to direct the main attack on the city. The obvious answer was dictated by the topography of the site-and the surrounding terrain. The city was enveloped by deep valleys on nearly all sides, and only at the southwest corner did a topographical saddle connect the mound with the neighboring hillock. The fortifications at this corner were specially strengthened, but nevertheless, the southwest corner (and the nearby city-gate) was the most vulnerable and most logical points to assault -

|

|

|

|

.

The excavations in the southwest corner were started in 1932, when Starkey cleared large amounts of stones heaped against the slope. Excavations here were resumed in 1983 (Area R) and it soon became clear that the stones encountered by Starkey were in fact the remains of the Assyrian siege ramp (Fig. 26).The siege-ramp of Lachish is the earliest, and the only Assyrian one, which is known today (Fig. 26). At its bottom, it was ca. 70 m wide and ca. 50 m long. The core of the siege-ramp was made entirely of heaped boulders collected in the fields around. It is estimated that the weight of the stones invested in the construction of the ramp was 13000 to 19000 tons.

Fig. 26. The southwest corner of the mound: the Assyrian siege-ramp and Area R

|

|

|

The stones of the upper layer of the ramp were found stuck together by hard

mortar, forming a kind of stone-and-mortar conglomerate, which was preserved

at a few points. This layer was the mantle of the ramp, added on top of the loose

boulders in order to create a compact surface, enabling the attacking soldiers and

their siege machines to move on solid ground. The top of the siege-ramp was crowned

by a platform made of red soil; being sufficiently wide, it provided even ground for the

siege-machines to stand upon.

Fig. 27. The façade of the city-wall at the point of the Assyrian attack

Above the siege-ramp were uncovered the fortifications which were especially massive and strong at this point. The outer revetment wall formed here a tower topped by a kind of balcony on which the defenders could stand and fight. The façade of the tower, built of mudbrick on stone foundations, was ca. 6 m high - preserved nearly to its original height (Fig. 27).Once the defenders of the city saw that the Assyrians are building a siege-ramp, they started to lay down a counter-ramp inside the main city-wall. Dumping here large amounts of mound debris taken from earlier levels of the mound, they constructed a large ramp, higher than the main city-wall, which provided them with a new defense line once the city walls fell to the enemy.

As a result of the construction of the counter-ramp, the south-west corner became the highest part of the mound. It was a very impressive rampart, its apex rising ca. 3 m above the top of the main city-wall. Some wooden make-shift fence or wall must have been erected here, but its remains were not preserved. Soundings in the core of the counter-ramp revealed accumulations of mound debris containing pottery of earlier levels, as well as limestone chips, which were dumped in diagonal layers.

|

|

|

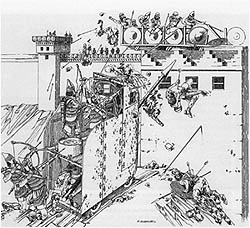

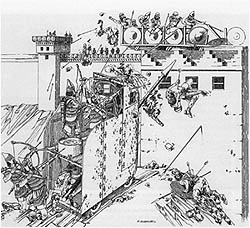

| The siege-machines were used by the Assyrians to destroy the defense line on the walls, and no less than five siege-machines arrayed for battle on top of the siege-ramp are portrayed in the Lachish relief. The South-African artist Gert le Grange who took part in the excavations, prepared an excellent reconstruction of such a siege-machine in battle (Fig. 28). The machine moves on four wheels, partly protected by its body, which is made in six or more sections for easy dismantling and reassembling. The ram, made of a wooden log reinforced with a sharp metal point, is suspended from one or more ropes, like a pendulum, and several crouching soldiers are moving it backwards and forwards. The defenders standing on the wall are throwing flaming torches on the siege-machine. As a counter measure, an Assyrian soldier is pouring water from a long ladle on the façade of the machine to prevent it from catching fire. The artist did not forget to add a cauldron containing water beside this soldier.

Fig. 28. The Assyrian attack: a reconstruction by Gert le Grange

The city gate is pictured in the center of this slab, but isolated and without connecting walls. The gate is represented as a single, simple doorway. The best preserved Judean warriors in these reliefs are those atop the gatehouse. Two earthen ramps covered with wooden logs are shown, with the right one reaching to the base of the gate. One of the most feared weapons of the day, the Assyrian battering ram ascends the ramp.

000000000000000000000000000000000

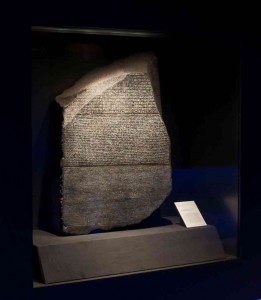

The following photos are of the famous Lachish Reliefs of Sennacherib at the British Museum. The photographs on this page were all taken by Mark Borisuk. We thank him for allowing us to share these excellent images. All of these pictures are linked to the high-resolution version and can be used freely for personal and educational use.

www.bibleplaces.com/newsletter/2002july.htm

|

|

|

-

|

- -

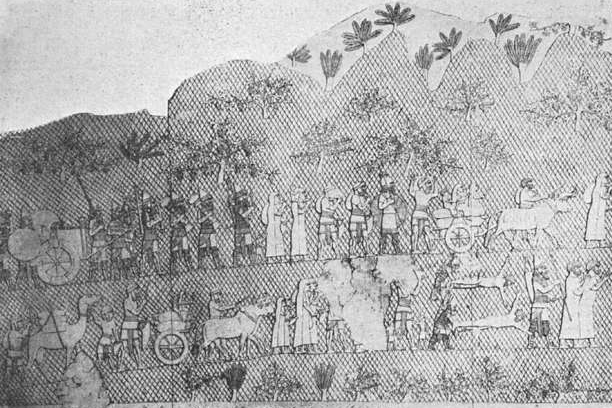

-The main assault on the city takes place just to the right of the gate and

includes multiple tree-covered ramps (five total including the right portion

of this slab). Four women and two men are shown being deported from the

city, while three naked Judeans were impaled on stakes. The deportees each

carry a bag over their shoulders. The impaled captives are depicted as already

dead, as can be seen by the forward tilt of their heads. Two Assyrian spearmen

affix the stake of the right man into the ground.-

The main assault is visible here also. At the bottom of the ramps are pairs of archers.

At the top of the ramps are the siege engines with their rams pounding against the

city’s defenses. A total of seven battering rams are visible in the entire attack

scene, the largest number depicted in any Neo-Assyrian battle relief.

|

|

-The end of two lines of people begin in this scene.

Assyrian soldiers bring up the rear of the top column.

They are dressed with conical helmets with earflaps, scale armor,

a short tunic, and high boots. Their dress resembles that of earlier archers,

but they carry only swords.

They carry items captured from the city, probably from the palace

of the governor of Lachish. Two soldiers pull a chariot, probably that

of the Lachish ruler. This is the only known Judean chariot to date

from any extrabiblical source.

|

The procession continues on this scene with more Assyrian soldiers carrying booty. Here the first three Assyrian soldiers follow the deportees. The first Assyrian soldier carries a scepter deliberately upside down. The next two hold large ceremonial chalices, similar to much smaller vessels found in the excavations. More deportees are shown in the bottom register. Two women lead two girls who are followed by a man directing two oxen hitched to a cart. The cart is filled with the family’s possessions and two small children sit on top. The oxen’s ribs are visible, probably reflecting the desperate situation of the Lachishites.

|

|

|

|

At the top right another man with an ox-pulled cart is shown. Riding on the cart are two women, one holding an infant. The lower column includes two Judeans stretched out on the ground. Their ankles are grasped by Assyrian soldiers who apparently just flayed these men alive.

|

|

|

|

Trees are depicted at the top, including what may be schematized olive trees and a grapevine. The upper column shows Assyrian soldiers leading three Judeans without headdresses. These men have curly hair and curly beards who may have incited the city’s inhabitants to resist Assyria until the end. Some of these men are shown being tortured, and one man on the bottom tier is being stabbed in the shoulder while the Assyrian soldier grabs his hair.

|

|

|

|

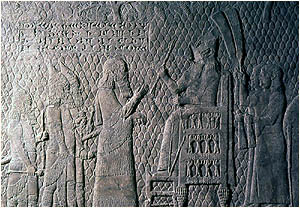

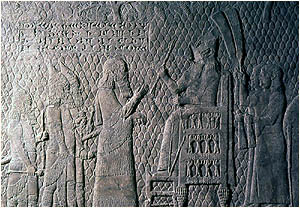

This scene focuses on King Sennacherib. These three slabs made up the northern side of the room and measure about about 15 feet altogether. Slabs 1-6 filled the western wall and Slabs 10-12 the northeastern portion. No slabs have been preserved of the southern or southeastern walls.

|

|

|

|

The procession leads to King Sennacherib who is seated on his royal throne in front of his tent and facing the city. The procession is likely led by the Tartan, the commander-in-chief of the army. Above the officials’ heads is an inscription identifying Lachish as the object of this campaign: “Sennacherib, king of all, king of Assyria, sitting on his nimedu-throne while the spoil from the city of Lachish passed before him.” Behind the king two eunuchs hold fans made of feathers.

|

|

|

|

Sennacherib’s face was destroyed in antiquity and his wrists, which were probably adorned with bracelets, were carved out (now restored with gypsum). The bracelets signified his kingship and the rosette decorations on them were official Assyrian emblems. The defacing of the king’s image was thus intended to symbolically reject his right of rule and may have occurred at the time of his assassination by his sons in 681 B.C. (cf. 2 Kings 19:37).

|

|

|

|

Sennacherib’s throne was mentioned in the inscription and obviously transported to Lachish from Assyria. The throne was decorated with ivory (cf. Solomon’s “throne of ivory”; 1 Ki 10:18), a fashion imported originally from Syria and Phoenicia. Twelve identical men support the throne and each have long hair and long beards. The throne also has a footstool which enables the king in his elevated position to rest his feet comfortably.

|

|

|

Go to the beginning of the Lachish reliefs!

http://prophetsandpopstars.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/02/lachish_siege_nineveh.gif

| Related Web Sites |

| Sennacherib’s Reliefs - the official page of the British Museum, which houses the reliefs.

Includes a picture of Slabs 10-12 (not depicted on this website).

The Assyrian Reliefs from “The Palace With No Equal” - On the website of the University of Lethbridge with a general description of the reliefs and links to some drawings of the slabs.

Art History, University of Wisconsin - some images of the reliefs, apparently only available to users on the school’s network.

Siege of Lachish - brief description of the battle from Norwich University.

Nineveh - with mention of the possibility of these reliefs depicting something other than Sennacherib’s 701 campaign. By the University of Texas.

A Brief Reexamination of the Degree of Specificity in Sennacherib’s Battle Reliefs of Lachish - by Paul Ash. This detailed and well-illustrated article was submitted to the Israel Exploration Journal for publication (but not accepted). The paper’s conclusion: “the details in topography and clothing have not in any way been drawn to depict specifically ancient Lachishites or Judahites.”

Assyrian Campaigns in Israel and Judah - an illustrated survey |

| Related Books

Ussishkin, David. The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib. Tel Aviv, Israel: Tel Aviv University Publications, 1982. Excellent work describing the reliefs as well as the archaeological excavations which correspond to the ancient Assyrian depictions. This book was the source for the descriptions on this page.

Russell, John Malcolm. Sennacherib’s “Palace without Rival” at Nineveh. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. |

-

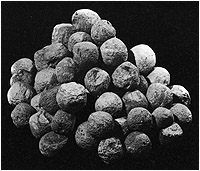

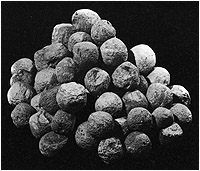

Twelve ‘perforated stones’ were discovered at the foot of the city-walls (Fig. 29a). These are large perforated stone blocks, with a flat top, straight sides, and an irregular bottom. Each of them is nearly 60 cm in diameter and weighs about 100 to 200 kgs. Remains of burnt, relatively thin ropes were found in the holes of two of these stones (Fig. 29b).

It seems that the ‘perforated stones’ formed part of the weaponry of the defenders.

The stones were probably tied to ropes and lowered from the wall in an attempt to

damage the siege-machines and prevent the rams from hitting the wall; they must have

dropped the stones on the siege-machines and moved them to and fro like a pendulum.

Fig. 30a-b. An Assyrian slinger depicted in the relief and slingstones from Lachish

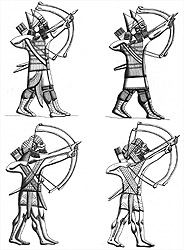

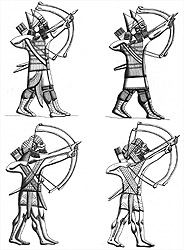

The Lachish relief displays slingers shooting at the walls as well as defenders shooting at the attackers, and many slingstones were indeed found in the excavations (Fig. 30a-b). These are round balls of flint or limestone, shaped like tennis balls, each weighing 250 gr or more.The Lachish relief displays Assyrian archers supporting the attack, and close to a thousand arrowheads were discovered in the excavation of the southwest corner (Fig. 31a-b). The arrowheads are not uniform in size or shape; they were mostly made of iron, and a few were made of bronze or carved of bone. Most of the arrowheads were uncovered in the burnt mudbrick

|

|

|

| debris in front of the city-walls. Apparently these arrows were shot by Assyrian archers at warriors standing on top of the wall. The discovery of so many arrowheads in such a small area shows how concentrated the Assyrian fire-power was. Many arrowheads were found bent - an indication that they were shot at the walls with powerful bows from close range.

The Lachish reliefs. Sennacherib constructed his magnificent royal palace, now known as the Southwest palace, in his capital Nineveh. The palace was largely excavated in 1850 by Sir Henry Layard on behalf of the British Museum in London. Centrally situated in the palace was Room XXXVI which contained the Lachish reliefs.

Fig. 31a-b. Assyrian archers depicted in the relief and arrowheads from Lachish

The walls of Room XXXVI were covered by the series of the Lachish reliefs, which was about 27 m long. This is the longest and most detailed series of Assyrian reliefs depicting the conquest of a single fortress city. Layard transferred most of the reliefs to the British Museum where they are presently exhibited to the public.

In consecutive order from left to right are portrayed the reserve consisting of horsemen and charioteers, the attacking infantry, the storming of the city, the transfer of booty, captives and families going into exile, Sennacherib sitting on his throne, the royal tent and chariot, and finally the Assyrian military camp.

The central scene depicts the attack on the city walls. The city-gate is shown in the center, being attacked by a siege-machine, and defended by Judean warriors (Fig. 14). Refugees carrying their belongings leave the city through the gate.

The inhabitants are portrayed leaving the destroyed city to exile, taking their belongings with them, a tragic picture of entire families forced out of their home. The families include men, women and children, and they carry their belongings in carts harnessed to oxen (Figs. 32-33). |

|

|

.

Facing the city and the deportees Sennacherib is shown sitting on his magnificently decorated throne, brought hither from Assyria (Fig. 34). The cuneiform inscription, carved in the background identifies the assaulted city as Lachish. Finally, behind the Assyrian monarch, are shown the royal tent and chariots and then the Assyrian camp.

| The Late Judean and Persian Period cities

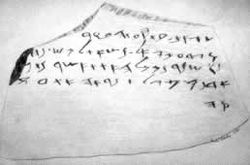

After a period in which Lachish was apparently abandoned, the settlement was apparently renewed and refortified (Level II). The Level II city was poorer, less densely inhabited, and had weaker fortifications than its predecessor. It was destroyed by fire during the conquest of Judah by the Babylonians in 587/586 BCE. Lachish is mentioned in Jeremiah 34 7 as one of the fortified cities in Judah that Nebuchadnezzar attacked.

-

Fig. 34. The relief: Sennacherib sits on his throne at Lachish-

A group of Hebrew ostraca, known as the ‘Lachish letters’ was found by the British expedition sealed beneath the destruction debris in the ruined city-gate. They date to shortly before the Babylonian conquest and were sent to a military commander

|

|

|

| named Yaush. These ostraca form one of the most important groups of pre-exilic

Hebrew inscriptions known today.

Level I dates to the Babylonian, Persian and Early Hellenistic periods.

During the Persian period Lachish served as a district center.

The settlement was refortified and a palace (The ‘Residency’) and a temple

(The ‘Solar Shrine’) were built here. The settlement at Lachish was abandoned

at the end of the Hellenistic period, in the second century BCE, and Marisa

(Mareshah) and then Eleutheropolis (Beth Guvrin) became the major cities

in the region. |

Publications

D. Ussishkin, Royal Judean Storage Jars and Private Seal Impressions,

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 223, 1976, pp. 1-13.

D. Ussishkin, The Destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib and the Dating

of the Royal Judean Storage Jars, Tel Aviv 4, 1977, pp. 28-60.

D. Ussishkin, Excavations at Tel Lachish - 1973-1977, Preliminary Report,

Tel Aviv 5, 1978, pp. 1-97.

D. Ussishkin, The ‘Lachish Reliefs’ and the City of Lachish, Israel Exploration Journal

30, 1980, pp. 174-195.

D. Ussishkin, The Conquest of Lachish by Sennacherib, (Publications of the

Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, No. 6), Tel Aviv, 1983.

D. Ussishkin, Excavations at Tel Lachish 1978-1983: Second Preliminary Report,

Tel Aviv 10, 1983, pp. 97-175.

D. Ussishkin, Levels VII and VI at Tel Lachish and the End of the Late Bronze Age

in Canaan, in: J.N. Tubb (ed.), Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages, Papers in

Honour of Olga Tufnell, London, 1985, pp. 213-230.

D. Ussishkin, The Assyrian Attack on Lachish: The Evidence from the Southwest

Corner of the Site, Tel Aviv 17, 1990, pp. 53-86.

D. Ussishkin, Excavations and Restoration Work at Tel Lachish: 1985-1994,

Third Preliminary Report, Tel Aviv 23, 1996, pp. 3-60.

D. Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish

(1973-1994), Volumes I-V, (Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology,

Tel Aviv University, No. 22), Tel Aviv, 2004.

D. Ussishkin, Symbols of Conquest in Sennacherib’s Reliefs of Lachish - I

mpaled Prisoners and Booty, in: T.F. Potts et al. (eds.), Culture Through

Objects: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of P.R.S. Moorey, Oxford,

2003, pp. 207-217.

Y. Dagan, Archaeological Survey of Israel: Map of Lakhish (98),

Jerusalem, 1992.

00000000000000000000000000

Durante el reinado de Roboam Laquis fue reforzada como fortaleza militar.[3] Más tarde el rey Amasías huyó a Laquis para escapar de sus conspiradores, pero fue encontrado y asesinado.[4]

Asedio por el rey asirio Senaquerib

El rey asirio Senaquerib sitió Laquis en 732 a. C. Desde allí, según el relato bíblico, envió a Rabsaqué, Tartán y Rabsarís con una poderosa fuerza militar, en un esfuerzo por hacer que el rey Ezequías se rindiese, mediante burlas y cartas que desafiaban a Yahveh; según la Biblia, como respuesta un ángel de Dios aniquiló a 185.000 soldados en una noche.[5]

Esclavos judíos tras el asedio de Laquis. Relieve asirio.Museo Británico,Londres

En una representación del sitio de Laquis, hallada en el palacio de Senaquerib en Nínive, la ciudad aparece cercada por un muro doble, con torres a intervalos regulares. La escena que muestra a Senaquerib recibiendo un botín de Laquis tiene la siguiente inscripción:[6]

“Senaquerib, rey del mundo, rey de Asiria, sentóse en un trono nimedu y revisó el botín (tomado) en Laquis (la-kí-su).”

Conquista por Nabucodonosor II de Babilonia

Cuando los babilonios, comandados por Nabucodonosor II, invadieron Judá, Laquis y Azeca fueron las dos últimas ciudades fortificadas que cayeron antes de que Judá fuese tomada.[7]

Las llamadas Cartas de Laquis (escritas en ostraca, dieciocho de las cuales fueron halladas en Tell ed-Duweir en 1935 y tres más en 1938) parecen estar relacionadas con este período. Una de las cartas, dirigida por una avanzada militar al comandante que estaba en Laquis, dice en parte:[8]

Vigilamos las señales de Laquis, según las indicaciones que mi señor dio, pues no vemos Azeca.

Este mensaje parece indicar que Azeca ya había sido tomada pues no se veían señales de allí. También es interesante que todas las cartas legibles tengan expresiones en las cuales se nombra expresamente el nombre de Dios, una práctica habitual en la época:

“¡Quiera

Yahveh [יהוה] que mi señor oiga hoy buenas noticias”

(Ostracon IV de Laquis)

Referencias [editar]

Part of the relief in the palace at Nineveh

oParte de un relieve del palacio de Asurbanipal en Nineve que muestra el asedio y ataque de las murallas de Lachish por las tropas asiriasws the attack on the city walls at Lachish

TRestos de la rampa construida por las tropas de Senaquerib para atacar las murallas de Lachish

Puerta de la Edad del Hierro de Laquis(Wikipedia)

A

thReconstrucción del templo dela acrópolis Lachish (izquierda) con escaleras que suben a la cella o cámara sagrada interior del templo y las escaleras de dicho templo de Lachish(derecha).(d

Fig. 7. A gold plaque portraying a naked Canaanite deity standing on a horse

A siege machine used by Sennacherib against the walls of Lachish

Máquina de asedio asiria usada en Lachish

Fig. 13. The Levels IV-III city-gate

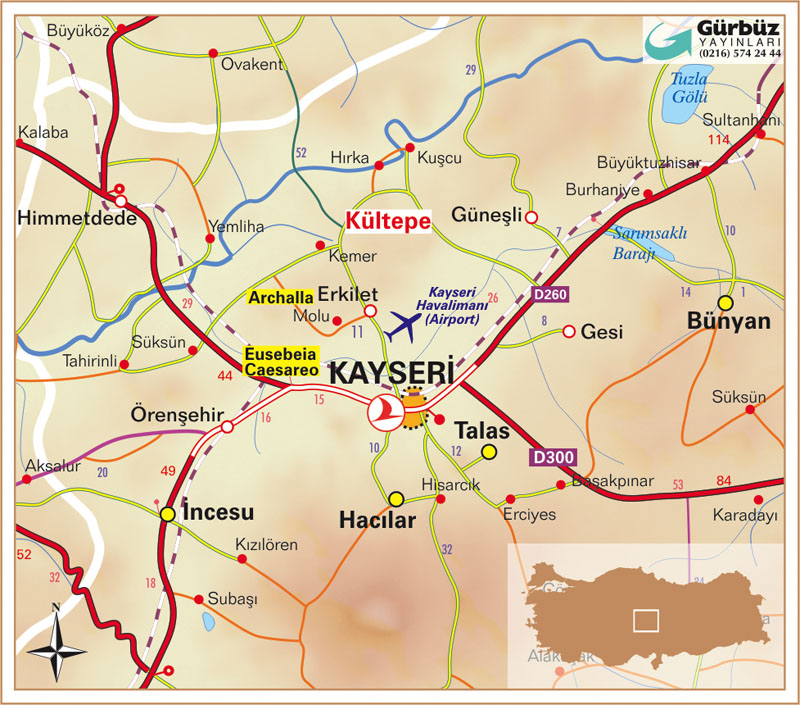

38°51′N 35°38′E / 38.85, 35.633) es el nombre de una antigua ciudad en Anatolia central, Turquía, antes llamada Kanes, Kanesh o Kârum de Kanesh en asirio, que significaba “la colonia mercantil ( asiria) de Kanes” (escrito como Karum Kaniş en turco moderno), y posiblemente Nesa en hitita.

38°51′N 35°38′E / 38.85, 35.633) es el nombre de una antigua ciudad en Anatolia central, Turquía, antes llamada Kanes, Kanesh o Kârum de Kanesh en asirio, que significaba “la colonia mercantil ( asiria) de Kanes” (escrito como Karum Kaniş en turco moderno), y posiblemente Nesa en hitita.

Excavaciones en el karum de Kanish,Turquia

Excavaciones en el karum de Kanish,Turquia

-

-