-

Situada en el centro de la Península del Peloponeso, Micenas da origen a la denominación de su época o cultura, la primera indoeuropea de Europa.

--

1.Puerta de las leonas.2. Circulo de tumbas.3. Casas micénicas (3) donde se encontró la llamada “Crátera de los guerreros”, expuesta en el Museo Nacional de Atenas. También se encuentra en esta zona un lugar de culto (4).

Desde aquí continúa la ascensión por la gran rampa (5) o vía real, flaqueada por muros , que fue modificada en el siglo III a.C. por la construcción de casas y comercios. Por ella se llega a la zona más alta del yacimiento, en la que se encuentra el palacio, pasando por el 6. Propileo monumental , en la actualidad es sólo un bloque de piedra caliza donde se sustentaba una columna 7. Se llega al gran patio 8. Palacio real.. A la derecha está la sala del trono y a la izquierda el mégaron. Al sur del patio, cerca de la sala del mégaron hay una escalinata que nos llevan a los pocos restos del Templo de Atenea 9. Casa de las columnas y diversas ruinas de otros edificios, en el llamado ” barrio de los artesanos”.10. Cisternas , que aseguraban el agua a la acrópolis en caso de asedio.

11. Puerta de entrada norte.

….

OTROS PALACIOS MICÉNICOS

http://www.bloganavazquez.com/tag/micenas/

De los palacios micénicos excavados, Tirinto y Pilos son los mejor conservados y los más interesantes. La mayor parte del palacio de Micenas cayó sobre la colina en que se levantaba; la Acrópolis de Atenas fue nivelada completamente y se construyó sobre ella; la fortaleza-palacio Cadmea en Tebas descansa debajo de una zona elegante de la población moderna.

Estos palacios han sido construidos en colinas de elevación importante y sus muros tienen varias puertas o entradas desde las cuales se dominan los principales caminos que convergen hacia ellos.

La población interior puede tener varias calles principales, como en Micenas, y el palacio está situado en el montículo más alto, por encima de las casas particulares y en ocasiones se comunica con ellas por medio de una rampa o de escaleras.

El bienestar de la población era incrementado mediante la construcción de caminos y el abastecimiento de agua. Él sistema de caminos micenico era extraordinariamente avanzado para su época y formaba una larga red que conectaba a las principales poblaciones de Argólida y de Mesenia, y probablemente también a Beocia y el Ática. Había puentes de piedra y con frecuencia su superficie estaba cubierta con grava. Los carros de guerra y los agrícolas podían viajar por ellos con menos saltos que en la época clásica posterior. Los abastecimientos de agua eran también refinados. El agua pasaba por los barrios industriales y por el palacio en tubos de terracota y era sacada por medio de un sistema de canales subterráneos, algunos de ellos revestidos con piedra. En realidad, los micenicos anticiparon casi todas las realizaciones que en el campo de la hidráulica conocieron los tiempos clásicos, salvo la invencion del cemento impermeable; cuando deseaban impermeabilizar utilizaban barro refinado o un emplasto de cal.

Cerámica. Museo Argos

http://images.google.es/imgres?imgurl=http://www.viaggiaresempre.it/10GreciaTirinto.jpg&imgrefurl=http://www.viaggiaresempre.it/fotogallery37oGreciaArgosTirinto.html&h=500&w=667&sz=45&tbnid=r3kHFizbBM4J:&tbnh=101&tbnw=136&hl=es&start=1&prev=/images%3Fq%3Dtirinto%26svnum%3D10%26hl%3Des%26lr%3D%26sa%3DG

Los talleres de los artesanos, así como las salas de los guardias, los almacenes y las cocinas están junto a los palacios, en la parte posterior o a sus lados. El palacio siempre es el centro económico e industrial del conjunto, así como el centro civil y militar. Las poblaciones aldeanas tenían sus habitaciones fuera del recinto amurallado, pero podían buscar protección en él en caso de ataque.

LA ESCRITURA LINEAL B indoeuropea.

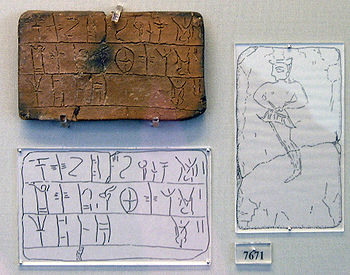

Tablilla MY Oe 106, encontrada en Micenas en la “casa del vendedor de aceite”, de circa 1250 a.C. Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Atenas, Tablilla 7671.

´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´´

El Lineal B es el sistema de escritura usado para escribir el griego de la época micénica, del 1600 al 1110 a. C. Precedió en varios siglos al uso del alfabeto para escribir la lengua griega. El lineal B es un silabario, es decir, que cada uno de los signos representa una sílaba.

En 1900, sir Arthur Evans encontró los primeros vestigios en Cnosos (Creta).

ORIGEN DEL SISTEMA DE ESCRITURA LINEAL B

La escritura lineal B desciende de la escritura Lineal A usada anteriormente por los cretenses entre los años 1800 a. C. y 1400 a. C. aproximadamente. De los 87 silabogramas que componen el sistema Lineal B, 64 se heredan del lineal A, mientras que sólo 23 son de creación micénica. Se piensa que el Lineal A, del que descendería este nuevo sistema de escritura, sería el utilizado para escribir sobre material blando, pero no poseemos este tipo de restos de Lineal A.

El periodo de implantación del Lineal B estaría situado antes del Heládico Reciente I (momentos anteriores al 1600 a. C.), cuando la cultura micénica estaba más en auge, pues parece ser que ya en el Minoico Reciente III estaba plenamente desarrollada a nivel lingüístico y paleográfico. Sabemos con seguridad de su uso durante el 1300 a. C. en Pilos, Micenas, Tirinte, Tebas, La Canea y Cnosos.

Acordar el lugar en el que fue creado este sistema de escritura es controvertido, pues para algunos investigadores su lugar de origen se encontraba en Creta y para otros en la Grecia continental. No se ha hallado ningún vestigio arqueológico ni paleográfico distintivo en ninguno de los dos lugares que permita a los estudiosos posicionarse definitivamente.

Corpus

Las tablillas se han clasificado por el lugar en el que se encontraron.

- Cnosos: KN (unas 4360 tablillas, sin contar las escritas en Lineal A y otras)

- Pilos: PY (1087 tablillas)

- Tebas:TH (337 tablillas, de ellas 238 publicadas en el 2002)

- Micenas: MY (73 tablillas)

- Tirinto: TI (27 tablillas)

- La Canea: KH (4 tablillas)

- Además, hay otras 170 inscripciones pintadas en vasijas.

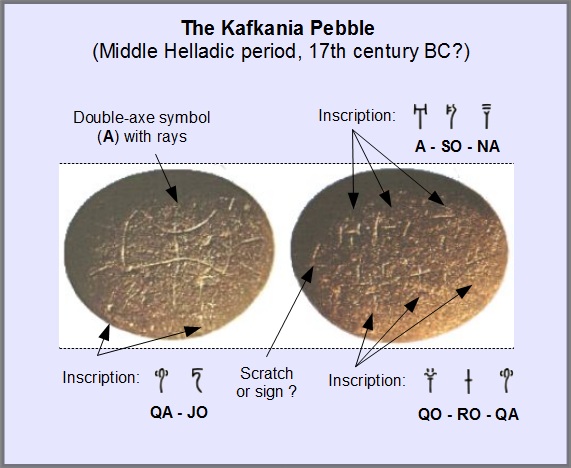

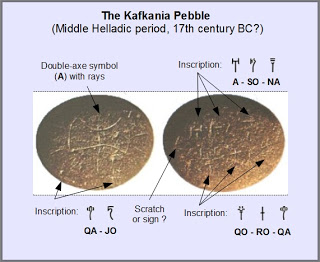

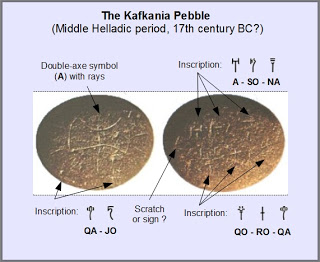

Si el guijarro de Kafkania (datado en el siglo XVII a. C.) es auténtico, sería la inscripción micénica más antigua y, por tanto, el testimonio más antiguo de la lengua griega.

Discovered on the Greek mainland, near the small township of Kafkania (or more precisely, Kafkonia, Καύκωνία in modern Greek), a few miles from the site of ancient Olympia (Αρχαία Ολυμπία) in 1994, it immedietely received much attention. Because it is likely the oldest known inscription in Linear B (tentatively dated to the 17th century BC), what it got was not just attention, but also the scrutiny, and even the scorn of scholars. Many believed - just because of the circumstances the pebble was found - that it cannot be genuine. The inscription - while relatively easily legible - also resisted attempts of easy decipherment. Some sources (I do not want to cite the book) claimed that “no one has ever seen a Linear B document with a ridiculous radiant axe symbol” or that “it likely featured the name of its discoverers”. But the case is unlike that of the fake Psychro tablet. Those who disparaged it should first take a look at the Idol of Monte Morrone and contemplate a bit on Linear A and Cypro-Minoan inscriptions. My mission is clear: what I attempt is to convince every reader who would have doubted its authenticity to understand the true background of this fascinating find!

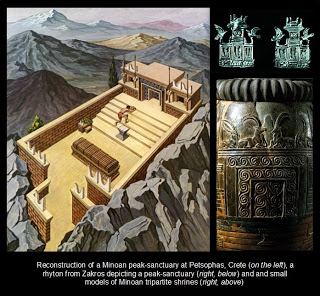

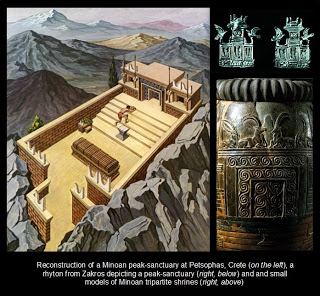

Relatively recently, I came across a video on youtube, made from the presentation of Colin Renfew on his excavations. Renfew and his team spent a good deal of work excavating Cycladic sites: his most important discovery was a peak-sanctuary at the island of Keros. What they discovered was truely amazing: they have not only uncovered a temple, where the solid bedrock was somehow an object of worship - other, even stranger habits of Early Bronze-Age Cycladic people began to surface. Next to the temple (at Kavos), they discovered sacricial deposits containing fragments from hundreds if not thousands of marble statuettes. When examined, the sacrificed objects turned out to be originating from all around the Aegean, including the Greek mainland. The temple was built atop the tiny rocky island of Daskaliou, yet the stones that once fomed its walls were not local, but all imported; and - against any sense or rational reason - from a considerable distance. What is more, a huge quantity of small, round rock-chunks - that is, pebbles - were found at the site, most of them gathered nicely in a special round room. When examined, they turned out to be all of a foreign origin. Even Renfew contemplated at this point, if the pebbles (that were all of a “standard” shape and size) were brought to the temple by visiting pilgrims as an act of worship.

This sort of ritual gift is still in use by some cults of modern era, although not for temples, but for graves. Take the example of Jewish burial customs. It is believed that by bringing a stone to the grave, one can contribute to it so the memory of the fallen shall remain ethernal. It does not takes much imagination to believe the same practice existed in some places of the Aegean, but not in the context of graves, rather in that of the sacred peak-sanctuaries.

Bringing pebbles to a sacntuary was a habit not limitied to the Cyclades. Most Minoan peak-sanctuaries contain a considerable quantity of pebbles (very likely of foreign origin), supposedly brought to the temple by followers visiting the shrine. Finding nice, rounded pebbles in a high mountaneous area, along with pottery shards, clay figurines and burnt ash are the main hallmarks archaeologists identify these hilltop shrines by. Up to date, at least 25 such sites were confirmed on Crete alone, and the number continues to grow.

Although the details of Kafkania site or the circumstances the pebble was found in are are hard to come across, and even detailed publications on the matter tend to be short and uninformative, the data I was able to glean seems to point to the fact that the Agrilitses Mound the pebble was found at, is a genuine peak-sanctuary, or a more generic sanctuary. It was apparently still in use in the Mycenean (Late Helladic) era. If so, then the conclusion seems clear: this pebble was the same as many thousand others, brought to the peak-sanctuaries by devout pilgrims. Just one difference: the man who brought this gift was a literate individual. He also wrought a tiny text into the pebble, in addition to the double-axe symbol.

Let us look at the artifact itself! First of all, the most prominent feature of the pebble is the huge double-axe symbol (compared to the syllabary signs). It is unlikely to be part of the script itself, but it still yields important clues on the nature of the artefact and the text. On the contemporary Crete (and likely also on the Mainland), the double-axes were a religious symbol: found on altars, paintings and carvings, even on jewellery depicting divinities. Because of this frequent usage, it is most probable that double-axes were not associated to a specific deity - rather, they seem to indicate a far more general concept: the presence of a god or divine power. It is also important to realize that the double-axe symbol was also part of the syllabary (Hieroglyphics as well as Linear A, even featured on the Phaistos Disc), with a phonetic value ‘A’. I will present evidence here that it is not entirely beyond reason to suppose the double-axe symbols were (literally) an abbreviation to the Minoan word for ‘god’, ‘divinity’. As for the “rays”, there is nothing special about them: even the Minoan artists tend to draw surreal representations of the axe (e.g. two axes are often embedded within each other).

As for the text carved onto this tiny piece of stone, trouble is imminent: due to erosion of the surface, many symbols are damaged or barely visible. The only obvious observation is that we have 6 or 7 signs on one side (in two rows) and two further ones, below the double-axe with rays. The most widely accepted reading is (following Godart): A-SO-NA QO-RO-QA and the reverse: QA-JO. It is interesting to see both the QO and the JO signs so typical of Linear B, but lacking from Linear A. Having studied the shape of these signs, I can confirm that their reading is correct: the shape of QO is identical to those on other Linear B documents, though the JO appears slightly different, somewhat archaic.

Unfortunately, some signs can only be read with doubt: the NA in the end of the first line is sometimes interpreted as DI (though I could not discern the sidestrokes characteristic of DI at all). Between the first and the second line, right before them there is a deep scratch - I am uncertain if it belonged to a (damaged, Linear A-like) RI sign continuing the first line, but (based upon the spacing) this is unlikely. In the second line, the secodn sign could also be KA (perhaps there is a circle around the strokes), but phonologically RO is much better (QO-KA-QA would be peculiar, if pronounceable at all). The last sign is barely visible, but was perhaps QA.

What does the text mean? This is the point when specialistst of Mycenean Greek and Linear B inscriptions begin to scratch their head. While QO-RO-QA could have been a proper name in Mycenan Greek (a lot of other names ending in -QA were found at Knossos and Pylos), the others do not admit a good meaning. Especially problematic is the phrase A-SO-NA. But if we look at it from a different perspective, taking all the Aegean scripts into consideration, not only Linear B, we might be able to get help. Because at Cyprus, on one of the Amathousian gravestones, the word A-SO-NA recurs, in a slightly different context: A-SO-NA • TU-KA • I-MI-NO-NA (a phase recurring twice in a longer text).

As for the meaning of A-SO-NA - if we looked outside of Greek as well - the Etruscan word aisuna (=’divine’) would offer itself as a viable parallel. Looking at the cited Eteocretan text, the meaning ‘divine’ can be fitted well with the context, if we equated TU-KA with Greek Tyche = Fortune (as a divinity, personification of luck). This way, the inscription would become: “I-MI-NO-NA [adj = of I-MI-N(O)] (blessed?) by divine Fortune”.

Now, if we go back to the pebble, and plug this meaning in, we might be able to get a good reading of the text. Despite the fact that it features a Greek-like name QO-RO-QA (a theonym?), it uses the adjective A-SO-NA, and not I-JE-RO (hieros) that would be expected from a native Mycenean Greek speaker. Thus, while the shrine might have been that of a genuine Greek divinity, the person who left this pebble apparently spoke a different language. In the light of this revelation, we may also re-interpret QA-JO as a derivation of some Non-Greek Aegean verb. Endings of this kind (-o) are relatively common in Minoan words attested in Linear A (e.g. KI-RO), where they likely represent past participles (e.g. KI-RO = ‘missed’, KI-RI-SI = ‘is missing’). Although this is nothing more than a wild theory (as we know no verb with QA- stem in Linear A), but it was nevertheless, worth considering. Alternatively (since it is on the reverse), the term QA-JO may not continue the text on the other side - it may be a simple epithet of the divinity, or even an abbreviation - who knows?

1 comments:

-

Glen Gordon said…

- Putting aside the controversy of the validity of the pebble for now, let’s focus on the equation A-SO-NA = *aisona ‘divine (adj.); god-offering (n.)’.

Contextually it makes perfect sense, particularly if treated as the noun rather than adjective and unites it with what we find in Etruscan and Eteo-Cypriot. This however would be an outlier, the only such form attested before 700 BCE.

My issue with this concerns what the proper etymology of this *ais- root is and there has been a lot published but nothing terribly substantial to make a dent in this mystery. At first blush, it makes sense that *ais- should have been borrowed from the culturally dominant group (ie. from Etruscan into Italic languages).

However, the word appears to be found several times in a myriad of Italic languages. It revolves around an o-stem *aisos (Marrucinian aisos ‘gods’, Venetic aisus ‘god’, Paelignian aisis ‘gods’) with a number of advanced derivatives (Oscan aisusis ’sacrifice’, Volscian esaristrom, Umbrian esōno- ’sacred’). There is also Latin erus ‘lord’ and the matter of the Celtic god Esus. Etruscan doesn’t have o-stem nouns and only attests to ais without final vowel.

What’s more, one possible Indo-European source comes to mind: *h₂eis- ‘to ask, to implore’.

Discovered on the Greek mainland, near the small township of Kafkania (or more precisely, Kafkonia, Καύκωνία in modern Greek), a few miles from the site of ancient Olympia (Αρχαία Ολυμπία) in 1994, it immedietely received much attention. Because it is likely the oldest known inscription in Linear B (tentatively dated to the 17th century BC), what it got was not just attention, but also the scrutiny, and even the scorn of scholars. Many believed - just because of the circumstances the pebble was found - that it cannot be genuine. The inscription - while relatively easily legible - also resisted attempts of easy decipherment. Some sources (I do not want to cite the book) claimed that “no one has ever seen a Linear B document with a ridiculous radiant axe symbol” or that “it likely featured the name of its discoverers”. But the case is unlike that of the fake Psychro tablet. Those who disparaged it should first take a look at the Idol of Monte Morrone and contemplate a bit on Linear A and Cypro-Minoan inscriptions.

My mission is clear: what I attempt is to convince every reader who would have doubted its authenticity to understand the true background of this fascinating find!

Relatively recently, I came across a video on youtube, made from the presentation of Colin Renfew on his excavations. Renfew and his team spent a good deal of work excavating Cycladic sites: his most important discovery was a peak-sanctuary at the island of Keros. What they discovered was truely amazing: they have not only uncovered a temple, where the solid bedrock was somehow an object of worship - other, even stranger habits of Early Bronze-Age Cycladic people began to surface. Next to the temple (at Kavos), they discovered sacricial deposits containing fragments from hundreds if not thousands of marble statuettes. When examined, the sacrificed objects turned out to be originating from all around the Aegean, including the Greek mainland. The temple was built atop the tiny rocky island of Daskaliou, yet the stones that once fomed its walls were not local, but all imported; and - against any sense or rational reason - from a considerable distance. What is more, a huge quantity of small, round rock-chunks - that is, pebbles - were found at the site, most of them gathered nicely in a special round room. When examined, they turned out to be all of a foreign origin. Even Renfew contemplated at this point, if the pebbles (that were all of a “standard” shape and size) were brought to the temple by visiting pilgrims as an act of worship.

This sort of ritual gift is still in use by some cults of modern era, although not for temples, but for graves. Take the example of Jewish burial customs. It is believed that by bringing a stone to the grave, one can contribute to it so the memory of the fallen shall remain ethernal. It does not takes much imagination to believe the same practice existed in some places of the Aegean, but not in the context of graves, rather in that of the sacred peak-sanctuaries.

Bringing pebbles to a sacntuary was a habit not limitied to the Cyclades. Most Minoan peak-sanctuaries contain a considerable quantity of pebbles (very likely of foreign origin), supposedly brought to the temple by followers visiting the shrine. Finding nice, rounded pebbles in a high mountaneous area, along with pottery shards, clay figurines and burnt ash are the main hallmarks archaeologists identify these hilltop shrines by. Up to date, at least 25 such sites were confirmed on Crete alone, and the number continues to grow.

Although the details of Kafkania site or the circumstances the pebble was found in are are hard to come across, and even detailed publications on the matter tend to be short and uninformative, the data I was able to glean seems to point to the fact that the Agrilitses Mound the pebble was found at, is a genuine peak-sanctuary, or a more generic sanctuary. It was apparently still in use in the Mycenean (Late Helladic) era. If so, then the conclusion seems clear: this pebble was the same as many thousand others, brought to the peak-sanctuaries by devout pilgrims. Just one difference: the man who brought this gift was a literate individual. He also wrought a tiny text into the pebble, in addition to the double-axe symbol.

Let us look at the artifact itself! First of all, the most prominent feature of the pebble is the huge double-axe symbol (compared to the syllabary signs). It is unlikely to be part of the script itself, but it still yields important clues on the nature of the artefact and the text. On the contemporary Crete (and likely also on the Mainland), the double-axes were a religious symbol: found on altars, paintings and carvings, even on jewellery depicting divinities. Because of this frequent usage, it is most probable that double-axes were not associated to a specific deity - rather, they seem to indicate a far more general concept: the presence of a god or divine power. It is also important to realize that the double-axe symbol was also part of the syllabary (Hieroglyphics as well as Linear A, even featured on the Phaistos Disc), with a phonetic value ‘A’. I will present evidence here that it is not entirely beyond reason to suppose the double-axe symbols were (literally) an abbreviation to the Minoan word for ‘god’, ‘divinity’. As for the “rays”, there is nothing special about them: even the Minoan artists tend to draw surreal representations of the axe (e.g. two axes are often embedded within each other).

As for the text carved onto this tiny piece of stone, trouble is imminent: due to erosion of the surface, many symbols are damaged or barely visible. The only obvious observation is that we have 6 or 7 signs on one side (in two rows) and two further ones, below the double-axe with rays. The most widely accepted reading is (following Godart): A-SO-NA QO-RO-QA and the reverse: QA-JO. It is interesting to see both the QO and the JO signs so typical of Linear B, but lacking from Linear A. Having studied the shape of these signs, I can confirm that their reading is correct: the shape of QO is identical to those on other Linear B documents, though the JO appears slightly different, somewhat archaic.

Unfortunately, some signs can only be read with doubt: the NA in the end of the first line is sometimes interpreted as DI (though I could not discern the sidestrokes characteristic of DI at all). Between the first and the second line, right before them there is a deep scratch - I am uncertain if it belonged to a (damaged, Linear A-like) RI sign continuing the first line, but (based upon the spacing) this is unlikely. In the second line, the secodn sign could also be KA (perhaps there is a circle around the strokes), but phonologically RO is much better (QO-KA-QA would be peculiar, if pronounceable at all). The last sign is barely visible, but was perhaps QA.

What does the text mean? This is the point when specialistst of Mycenean Greek and Linear B inscriptions begin to scratch their head. While QO-RO-QA could have been a proper name in Mycenan Greek (a lot of other names ending in -QA were found at Knossos and Pylos), the others do not admit a good meaning. Especially problematic is the phrase A-SO-NA. But if we look at it from a different perspective, taking all the Aegean scripts into consideration, not only Linear B, we might be able to get help. Because at Cyprus, on one of the Amathousian gravestones, the word A-SO-NA recurs, in a slightly different context: A-SO-NA • TU-KA • I-MI-NO-NA (a phase recurring twice in a longer text).

As for the meaning of A-SO-NA - if we looked outside of Greek as well - the Etruscan word aisuna (=’divine’) would offer itself as a viable parallel. Looking at the cited Eteocretan text, the meaning ‘divine’ can be fitted well with the context, if we equated TU-KA with Greek Tyche = Fortune (as a divinity, personification of luck). This way, the inscription would become: “I-MI-NO-NA [adj = of I-MI-N(O)] (blessed?) by divine Fortune”.

Now, if we go back to the pebble, and plug this meaning in, we might be able to get a good reading of the text. Despite the fact that it features a Greek-like name QO-RO-QA (a theonym?), it uses the adjective A-SO-NA, and not I-JE-RO (hieros) that would be expected from a native Mycenean Greek speaker. Thus, while the shrine might have been that of a genuine Greek divinity, the person who left this pebble apparently spoke a different language. In the light of this revelation, we may also re-interpret QA-JO as a derivation of some Non-Greek Aegean verb. Endings of this kind (-o) are relatively common in Minoan words attested in Linear A (e.g. KI-RO), where they likely represent past participles (e.g. KI-RO = ‘missed’, KI-RI-SI = ‘is missing’). Although this is nothing more than a wild theory (as we know no verb with QA- stem in Linear A), but it was nevertheless, worth considering. Alternatively (since it is on the reverse), the term QA-JO may not continue the text on the other side - it may be a simple epithet of the divinity, or even an abbreviation - who knows?

- Putting aside the controversy of the validity of the pebble for now, let’s focus on the equation A-SO-NA = *aisona ‘divine (adj.); god-offering (n.)’.

Contextually it makes perfect sense, particularly if treated as the noun rather than adjective and unites it with what we find in Etruscan and Eteo-Cypriot. This however would be an outlier, the only such form attested before 700 BCE.

My issue with this concerns what the proper etymology of this *ais- root is and there has been a lot published but nothing terribly substantial to make a dent in this mystery. At first blush, it makes sense that *ais- should have been borrowed from the culturally dominant group (ie. from Etruscan into Italic languages).

However, the word appears to be found several times in a myriad of Italic languages. It revolves around an o-stem *aisos (Marrucinian aisos ‘gods’, Venetic aisus ‘god’, Paelignian aisis ‘gods’) with a number of advanced derivatives (Oscan aisusis ’sacrifice’, Volscian esaristrom, Umbrian esōno- ’sacred’). There is also Latin erus ‘lord’ and the matter of the Celtic god Esus. Etruscan doesn’t have o-stem nouns and only attests to ais without final vowel.

What’s more, one possible Indo-European source comes to mind: *h₂eis- ‘to ask, to implore’.

HISTORIA DEL MUNDO ANTIGUO: GRECIA. Tema I.Mundo Minoico.Tema II. Micenas.

Autor: VÁZQUEZ HOYS ANA Mª, editorial Sanz y Torres

Carrera: HISTORIA

Asignatura: HISTORIA ANTIGUA UNIVERSAL

Curso: PRIMER CURSO GRADO.

Tipo: TEXTOS BÁSICOS

Edición: 1ª – 2007

Páginas: 750 páginas.

ISBN: 9788496808003

Tamaño: 28×22

Idioma: ESPAÑOL

- Ventris, Michael; Chadwick; John (1953). «Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives». The Journal of Hellenic Studies 73. 84-103. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0075-4269(1953)73%3C84%3AEFGDIT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Y.

- Alberto Bernabé Y Eugenio R. Luján. (2006). «Introducción al Griego Micénico. Gramática, selección de textos y glosario». Monografías de Filología Griega. 18.

- Varios autores (2007 para la publicación en Inglés.). «A history of Ancient Greek: from the biginnings to Late Antiquity.». Cambridge University Press..

- O. Hoffman, A. Debrunner, A. Scherer. (1973.). «Historia de la lengua Griega.». Editorial Gredos, Madrid..

- Martín S. Ruipérez y José Luis Melena. (1990). «Los Griegos micénicos.». Historia 16.

…..

Archivado en: ACTUALIDAD, ARTÍCULOS, Arqueologia, Arte Antiguo, Ciudades, Cultura clasica, Curiosidades, Europa, General, H. Grecia, HISTORIA ANTIGUA, Hombres de la Historia, Mujeres de la Historia, Noticias de actualidad, OPINIONES, PERSONAJES, PERSONALÍSIMO, VIAJES

Trackback Uri

Me pregunto, ¿cómo se ha establecido -tentativamente- la cronología del guijarro de Kafkania? ¿por un contexto estratigráfico? En el texto se menciona que las circunstancias del hallazgo “no están claras”, por lo que entiendo que el criterio estratigráfico no puede ser considerado. El guijarro en sí puede tener una enorme antigüedad, así que lo que se necesita es la datación de cuándo fue grabado. Hay algunos tipos de pruebas físico-químicas para tratar de datar grabados en rocas u otras superficies, pero no sé si fueron aplicadas aquí… ¿algún trabajo específico sobre esto?